Internal priorities would have counted against any capital ship continuation. With the quick finish hulls completed any advantage one or two more capital ships offered would be limited in the situation facing the HSF. Better returns were possible by prioritizing the U-boat fleet IRL and I don't see anything to alter this assessment. Since the 5BS is marginal to this narrative I didn't actually specifically think of any particular one. If I had to be pedantically accurate, I'd have to go check the historic records.Greatly enjoying the read.

You don't think there was the slightest chance of finishing Salamis in time for TTL Jutland, if it was given the same priority as the other 3 ships present?

Also, it may be in the text but i missed it, do the british have more QEs and Rs present TTL compared to the OTL battle? Which QEs does 5th BS has?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Battle of Jutland - 1916 (The Battle of the Battlecruisers.)

- Thread starter Tangles2

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 8 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

2. Prelude 3. Movement to contact. 4. First Blood 5. The British Battlecruisers Losses 6. The Screens collide and end of contact 7. The Immediate Post-Battle Aftermath. 8. The Longer-Term Impact on WW1 Naval Operations and Postwar Legacy. 1. PrologueWatch this space!Would there be further happenings between the damaged ships trailing behind, Australia vs Von der Tann and Seydlitz? Would the germans get a FIFTH british BC destroyed?

Coulsdon Eagle

Monthly Donor

Hi Tangles2,

Enjoying the timeline despite the RN taking a pasting. Although it appears one-sided it is IMHO a realistic possibility given Beatty's force is less 5BS in exchange for 3 Invincibles / Indefatigables. Why is the poor old Indefatigable always doomed? remember one wargame where she sunk Goeben in the Med - far better!

Did the RN learn nothing about the destruction of Inflexible at Stanley?

Enjoying the timeline despite the RN taking a pasting. Although it appears one-sided it is IMHO a realistic possibility given Beatty's force is less 5BS in exchange for 3 Invincibles / Indefatigables. Why is the poor old Indefatigable always doomed? remember one wargame where she sunk Goeben in the Med - far better!

Did the RN learn nothing about the destruction of Inflexible at Stanley?

The pendulum of battle will turn. Good AH still reflects basic fundamentals, one of which I believe in is 'God marches with the big battalions'. Obvious force mismatches will impact on the field of battle (soon to be shown). This can be subverted by things like good/bad leadership etc, (which is usually recognized at the time), yet it remains fundamental if the yarn is to remain believable. IOTL Jutland the subverting factor was the poor munitions security of the RN impacting on losses. Given parity of this it was quite possible for Jutland IOTL to have been one BC apiece, Queen Mary v. Lutzow, had the RN had the same procedures as the HSF, yet it was only by luck that Lion avoided the fate of the other 3 BC. I have run with this failure in the narrative, but it is still founded in the historical fact, not purely RN bashing.Hi Tangles2,

Enjoying the timeline despite the RN taking a pasting. Although it appears one-sided it is IMHO a realistic possibility given Beatty's force is less 5BS in exchange for 3 Invincibles / Indefatigables. Why is the poor old Indefatigable always doomed? remember one wargame where she sunk Goeben in the Med - far better!

Did the RN learn nothing about the destruction of Inflexible at Stanley?

For the Stanley comment I would say in context yes, it was very possible. ITTL it is a one-two sucker punch, Coronel then Stanley, to a moribund huge service after over a century of no major conflict, and barely weeks into a war with a modern opponent. The institutional inertia would be immense to protect the prestige of the service. With a convenient scapegoat in Sturdee and the destruction of the East-Asia squadron it is quite probable in those circumstances that any post-mortem would be lacking in 'rigor' shall we say. Just look at the failure to address the issues Dogger Bank raised in 1915 and it is easy to see a similar attitude to Stanley. It was only after the IRL Jutland failures that parallels would actually be drawn, and with that 'victory' even then the changes were slow to be adapted.

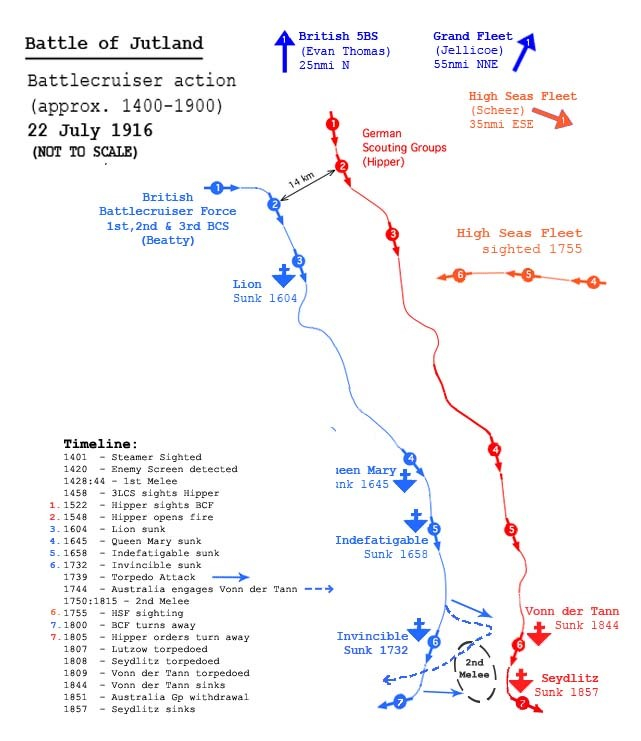

6. The Screens collide and end of contact

Part Six

1736, 22 July 1916, HMS Southampton, North Sea, 220 miles from Rosyth

Rear Admiral Napier was quite happy wearing two hats, being both the commander of the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron, and senior officer commanding the entire screen of the 1st BCF, which in effect totaled 13 Light cruisers and a total of 24 destroyers. In the months of his command, they had drilled and worked together, and the challenge represented one of the most satisfying periods of his life. But all the preparation and training in the world had become victim of the other great timeless navy truism, no plan survives contact with the enemy. Quite frankly as commander of the screen he was having a bad day, and his sour mood at the moment reflected it.

From the moment of the contact with the extreme edge of the screen events had seemingly conspired to create factors to disorganize his screen. The initial contact had collapsed the ships on that flank towards the fight, and the vicious little engagement had further disorganized the sections involved. By the time both sides had broken contact he had not only lost a destroyer, but the dense low smoke and rapid interplaying of small ships in melee had broken the formations up, not to mention causing damaged ships to fall out of action. This followed by the Battlecruiser force reversing course and then the second course change by Beatty had left the vast majority of the screen badly out of position, trailing the battle line instead of being ahead to do its job, and be best positioned to intervene for defence or attack. With only a few knots advantage it had taken far too long for the screen to regain a leading position, not helped by receiving the order "Destroyers clear the line of fire!". This had basically forced his ships to essentially follow three sides of a square in regaining the lead whilst moving up the western disengaged side of the battleline. Then firstly the Australia being forced out of the line, followed unbelievably by the loss of three battle cruisers, had obliged him to leave ships in each case for support or rescue duties.

Finally, barely half an hour ago, he had mustered the remaining balance of his screen and was in a position to attack at last. Looking through his glasses he could see the forces of the enemy screen in the van of their formation. These were the ships that he would engage, and in his mind, was assessing what he was seeing. Even having left ships to support stragglers, there still remained well over twenty torpedo boats there. Individually smaller and more lightly armed than his ships, he had only about 3/4 of his original destroyer force in hand. More powerful individually but offset by their number it would be a roughly equal battle. What he had was his three squadrons of light cruisers, and to his eye there where at most 4-5 to oppose his baker's dozen. This was the hammer to crack the defense, and if he committed his entire force then he was sure that he could get two or three of their big ships if he employed the screen en-masse.

Increasing further his foul mood, carefully hidden behind his calm exterior, his professionalism was battling with a profound dissatisfaction. Partly this was the events of the day, the screening issues and the losses already suffered, and partly was his current inactivity. He could see the enemy, and was in a prime position to inflict damage on them, but Admiral Hood had ordered him to wait for now. He could only watch and wait in anticipation, and could feel the anger and eagerness on his bridge. The Royal Navy as an institute was not used to coming off second best, and for all that events had not gone their way to date, He was certain that there wasn’t a single matelot in the screen who wasn't eager and champing to reverse that fact. This intense focus was snapped abruptly by an aghast call, "Sir, the flagships blown up." Causing him to spin around in shock once more, to confirm with his own eyes despite his disbelief. For some 30-40 seconds he just stood, staring, initially too surprised in conflicted disbelief to organise his thoughts coherently at first, before the logical portion took control and recognised that he was now the one in the box seat, scanning the disrupted battleline behind and the visible dispositions across to the enemy. The chain of command was clear in the Battlecruiser force, Rear Admiral de Brock was in command of the 1BCS, now reduced to the sole ship, HMS Princess Royale at the head of the line, and was his junior. While controlling the Battlecruiser force, his promotion was only recent and up until May 1915, he had actually been the previous Captain of Princess Royal itself.

Overall command was now his, and experience and professional instincts made him pause for a further moment, analyzing if it was workable or just his instinct to lash out at the losses endured, before after a brief nod to himself, turned to his flag Yeoman on the bridge of HMS Falmouth and said, "Get a radio signal out to the Grand Fleet and 5BS with an update and advice I am attacking." Evan as he could hear the growl of approval from those around him, he added, "General signal to the screen, all ships: general attack - torpedo," and added as an aftermath to the surrounding bridge personnel, "Let loose the dogs of war," with a tight grin.

1742 22 June 1916, Skagerrak, North Sea, 250 nautical miles from Rosyth

Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedecker’s IInd Scouting Group had reformed ahead of the Hipper's battle cruisers fairly quickly after the initial contact melee at the start of the action. This job made easy by the few heading changes during the slugging match that had developed between the capital ships of the two forces behind him. He had been forced to detach several of his torpedo boats to provide support for the lagging Vonn der Tann and Seydlitz, but still had over two dozen available in support of the four light cruisers under his command. He had watched with increasing foreboding as the British screen had steadily reformed ahead of their line opposite. For the last half an hour or so they had just paced his own forces, visible across the dozen kilometres separating them, and he could see they had three times the cruiser force he had, just hovering forbiddingly. For all he had an edge in numbers of smaller vessels, he was at a loss as to why they had not attacked before now. Even the most partisan of officers of the Imperial German Navy had never accused the Royal Navy of timidity, and the longer he had studied the serried lines of cruisers and destroyers shaken out opposite him, the greater the tension had built in his own mind, simply waiting for them to act. When they did, he knew his own forces were going to be stretched to the limit to respond, and the analytical part of his training already indicated that the odds would be badly against him. The destruction of a fourth enemy battlecruiser was a passing distraction, preoccupied as he was with anticipation of whatever the opposing screen might do. So, when at 1754, he saw the entire leading force swinging in to lunge towards Hipper's ships it actually came as a relief from the rising tension. Even as he was giving the orders to martial his own forces to counter attack and interpose themselves between the lines. A distant small distracted part of his mind, briefly mused if the delay had been deliberate, simply to evoke the tension felt before committing to attack, as he and the ships and men under his command steeled themselves for what was undoubtedly going to be a bloody and brutal confrontation. This distraction was lost as the first shots began arriving and he committed himself fully to the chaos of battle unfolding.

1741, 22 July 1916, HMS Narborough, 13th Destroyer Flotilla, North Sea.

LT Reginal Barlow was still a comparative rarity in the RN, being a Royal Naval Reserve officer from P&O and not a regular, and now acting as an Executive Officer on a M-class Destroyer. Having initially been a freshly appointed 3rd officer on the British India Steam Navigation cargo-liner Bankura in 1913, he had followed the practice of most of British officers of the major Royal Mail Ship navigation companies by joining the Royal Navy Reserve. He had made only a single cruise to Asia by 1914 when the company had amalgamated with P&O, and on the outbreak of war volunteered to serve with the tacit encouragement of his employers. Initially posted as a Sub-lieutenant to a destroyer of the Harwich Patrol and had found he thrived in the active role, despite the hard lying conditions. His basic competence and youthful enthusiasm for the job had seen him promoted to LT, and by early 1916 he was posted as exec of the Narborough. Initially part of the Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow he had found the lack of action, not to mention the freezing cold, incredibly boring and had thrown himself into his job. Fortunately, in May Narborough was transferred to the 10th Destroyer Force to be part of the screen of the Battlecruiser force based out of Rosyth, much to the pleasure of both himself and the rest of the ship's crew.

The day had initially looked like being a repeat of the earlier uneventful May sortie, up until shortly after noon, when a sighting of smoke to the east by Obdurate, one of the Narborough half-section had triggered a brief but confusing action with a number of German torpedo boats. Last ship in line, Narborough had followed its three sisters into action, with 'Reggie' in his usual action station with the rear 4-inch gun.

In the subsequent brief but fierce action, charging through a confused melee in the low obscuring fog of smoke, left by the wild interweaving of ships in the largely calm conditions, she had become separated from their companions. In the midst of a flurry of sudden short-range exchanges as ships appeared and disappeared at random, whilst trying to identify and engage targets, he had heard a detonation forward and felt a sharp shudder underfoot, he knew the ship had been hit as it suddenly veered sharply away to port. Leaving the gun to the mount petty officer in charge, he was rushing forward and fearing the worst when he was met by a runner at the forward funnel, with the news that the bridge had been hit and the captain was down. He arrived to find three still bodies and learned that a small calibre shell had burst directly under the tiny bridge causing casualties and disabling the forward 4-inch mount. By the time he had regained control the ship had already completed two full circuits through several bands of smoke and he found he had no idea where he was or the location of the rest of his half-section or the enemy. Still moving at over 25 knots and peering ahead he thought he could see a ship ahead heading east and, thinking it most possibly one of their own followed it. Only a few moments later they burst out into clearer conditions, and to the sudden realisation that they were taking station at the rear of a line of three or four German ships just a few cables ahead. The abrupt reversal of their course rapidly back into the smoke had also awoken the Germans to the fact that Narborough was not one of their own, and it was pursued by shells as disappeared back into the mirk.

After breaking north and then back west for some minutes the Narborough had emerged some quarter of an hour later to find itself in seeming isolation with startlingly not another ship in immediate sight. With his radio destroyed, and only a generalised idea of his location, he elected to follow the distant smoke cloud on the horizon to the south. As they closed on the smoke it resolved into another ongoing action, eventually revealed as the battlecruiser Australia, accompanied by two destroyers, exchanging fire with a German battlecruiser, also with a pair of escorts. Challenged by HMS Turbulent his response had been the ships number followed by: "Captain dead, no Comms, permission to join." With the brief confirmation, Narborough had fallen in behind the trailing HMS Termagant, and for the next period of time the three had acted as screen to the Australia, whilst being spectators to the slow relentless exchange as both battling ships were each hit several times, damage increasing and guns falling silent. At 1755 he saw the signal run up the Turbulent mast, "General Signal: Torpedo attack, conform." flying for some seconds while its two companions acknowledge, then with the dip of execute, all three turned towards the distant Vonn Der Tann.

On the bridge of Narborough, despite the mute evidence of the silent gun on the foredeck before him, Barlow felt an intense excitement at being in command as his ship drove forward to attack the enemy battlecruiser. The larger and faster T-class ships ahead of him slowly opened a slight gap and he could see two German ships curving to intercept their thrust short of its target. With events developing rapidly as the ships closed, he altered Narborough’s heading slightly to use the others funnel smoke to mask his own approach, as the guns of the five converging vessels were firing rapidly as the range shortened. Even as this was happening, he caught the surprised report from his signalman, "Australia's also closing sir!" A quick glance over his shoulder confirmed that the battlecruiser had also swung to port and was now acting like some oversized destroyer, charging on a sharply closing bearing to the limping smoke shrouded German ship ahead. With a wild laugh he couldn't help but respond, "The more the Merrier, flags!" before concentrating on the task in hand. Ahead he could see first one, then a second hit on the Turbulent, and the flash of another on the Termagant, but perhaps, due to the smoke and separation, for the moment no one seemed to be actually firing at the wildly charging Narborough. His own guns, their arcs opened by the course change, were now firing as well, and he nodded with satisfaction seeing a flare blossom on the lead Torpedo boat. Again, his ship seemed to be enveloped in a brief shroud of concealing funnel smoke, before suddenly breaking into the open exposing a plodding, Vonn der Tann, broadside on and hardly moving at less than 10 knots, "target Battleship to Port, engage as bearing, He shouted out to his sole Sub-lieutenant now at the tubes. "Hard a-starboard he ordered the Coxswain, as the range dropped to under 4,000 yards, clinging to the bridge screen as the ship heeled sharply with the radical turn. For the first time the Vonn der Tann seemed to recognise its threat and one or two of its secondary armament began throwing shells in their direction, but too few and far too late. As the ship swung upright, he could hear the thump one after another as the four torpedoes leapt into the water. Even as another radical turn sought to escape danger, his eyes remained rivetted on the target. At first nothing as the ship ploughed on seemingly unaware of its danger, but finally sluggishly it seemed, he could see a slight bearing change of its bow as it sluggishly began to turn. Unconsciously he found himself softly muttering, "Come on…, come on…," until unbelievingly first one then another huge spout arose from the Vonn der Tann's stern quarter. "Yes!" he couldn't stop a jubilant bark, and giving a brief un-officer like hop, before getting himself under control, then realising it had been lost in the general crowing, as an equally joyous roar of euphoria swept his ship, even as it began wildly changing course in withdrawal. His successful actions during the day would subsequently earn him a DSO and ensure him senior command with P&O in the future, and unbeknown to him eventually a carrier command in the Second World War.

1744, 22 June 1916, SMS Von der Tann, North Sea,

Kapitan zur See Hans Zenker, Captain of the Battlecruiser Von der Tann had long known is beautiful ship was increasingly in trouble. Laid down in 1907, she represented Germany's first attempt at designing a ship to meet the modern battlecruiser concept. Her very success and durability reflected the intensity and amount thought that had gone into the initial work to conceptualise her design. But despite this success she still represented the oldest and smallest of the modern German battlecruisers, being barely two-thirds the size of later ships. So, despite the excellence of her design, she still simply lacked the mass to absorb the degree of punishment of the others and was the most susceptible of the to the steady accumulation of damage inherent in any long slugging match.

The action had started well with the rapid and effective fire initially knocking an Indefatigable class ship out of the line, if only temporarily as it occurred. But despite continued hits on the opposition, the simple fact that she occupied the tail position against more numerous foes, ensured that multiple opponents engaged her when she could only effectively reply to one. The British ships had each picked an opponent at the start of the action, but that had translated into initially three ships and later two in the British line all firing at his own. By the time the destruction of two Royal Navy heavy ships, had reduced it to a one-on-one contest, the Vonn der Tann had already suffered significant damage as a result. At this point his ship had now been hit 12 times, with Both Anton and Dora turret on the disengaged side out of action. Anton turret was burnt out from a direct hit. Dora turret had been penetrated through its thin rear armour and thought the shell had failed to detonate it had killed or injured most of its crew and the shock from a shell impacting the barbette had jammed it. Bruno turret on the engaged side had suffered damage to one recoil mechanism, whether due to a near miss or the simple shock of the ship firing its main armament so regularly was not known as yet. She was down to two turrets, one firing at reduced rate, and both firing under local control as another hit had destroyed the main rangefinder.

Another shell from the same salvo that had wrecked Dora turret had impacted the after funnel and causing the ship to lose speed. For a while it had dropped out of engagement by an opponent. But as it fell further back, separated from Hipper's main battle line, it found itself once more exchanging blows with the Australia, similarly lagging from the British line due to its earlier damage. Again, hits began to accrue and despite his crew’s best efforts to keep her in action. Everywhere it seemed, a struggle against the incursions of fire and water was being waged. A shell had pitched short near the stern, flooding an after-boiler room and filling the ship with hundreds of tons of seawater. By now her speed was down to less than fourteen knots and reducing further as she wallowed deeper in the water. She had struck her opponent at least five times in the most recent exchange as the range had reduced leaving her afire in two places but in turn lost Bruno turret, so now only Caesar, the aft turret continued to fire back. Her opponent, while continuing to burn fiercely aft, never ceased to return fire with regular reduced four-gun salvo's. Captain Zanker now feared the worst but would continue to fight back while he effectively could regardless.

At 1745, shortly after another eruption in the distant ongoing exchange ahead, what he feared most came into reality. Suddenly he could see destroyers bearing down on his struggling ship, obviously intending to attack. Even as the two accompanying torpedo boats V248 and V189 moved to interpose, he could see the Australia, also now swinging about to close. With few of his secondary guns still in action, and all her former lithe speed robbed, he knew what was about to happen. Even as he spied a new threat emerged from the smoke, Von der Tann suffered yet another hit from the closing Australia that fully detonated against the base of the rear funnel. Her deck, already weakened by the earlier hits and unarmoured funnel, partially collapsed into the hole, and forcing the crew out of the machinery spaces. Even as the ship lost power, he could see the destroyer launched threat closing. Despite her helm being hard over and her bow swinging oh-so-slowly, he knew the effort would prove futile. First one, and then a second struck her after quarter, sending mast height spouts into the sky and penetrating the hull. Already Lamed and with an enormous cloud of smoke emanating from her, her shafts warped and rudder jammed she now slowly sagged to port as she coasted to a stop. As hundreds of tons of additional water now surged into the gaping holes below her waterline, she steadily began to list to starboard, her stern obviously rapidly filling. Without power to fight the flooding Zenker gave the inevitable order to abandon ship and with her guns now silent, her crew commenced to swarm upon deck, casting buoyant objects into the calm seas as she slowly coasted to a halt. Nearby, both her escorts also succumbing after their futile efforts at protection, would be soon joined by HMS Termagant in sliding below the waves.

With the command "All hands. Abandon ship" given at 1816 it was all Kapitan zur See Zenker could do was watch and await the final plunge of his beloved Von Der Tann. Already he could see that the Australia had ceased fire and was circling at a distance, topsides now sparsely crowding with observers despite a still smouldering fire in its stern superstructure. He stood contemplating as crewmembers took to the water as the remaining two British destroyers closed in to recover survivors of both sides. There was nothing more that could be done here he sighed; his ship had fought to it's last. No ship built of metal could withstand such an onslaught, yet Vonn der Tann had for so long. For all that, there were limits and it was now time to save his brave crew, that integral ships portion not made of metal. They had done all that could reasonably expected and more, and whatever the result of the action it was time to ensure the escape of as many as possible. It was to take nearly a further half hour before standing soaked on the deck of HMS Narborough, tears streaming unnoticed down his cheeks and surrounded on its massively over-crowded deck by recovered sailors all watching the final moments of his lovely command. Ever lady like she had briefly straightened upright before settling slowly stern first before finally slipping with little fuss beneath the surface of the North Sea, taking 303 of her 923 officers and crew with her.

1742 21 July 1916, HMNS Australia, North Sea

Despite its best efforts it had proved that the Australia had lacked the necessary knot or two or speed to successfully close with the rest of the Battlecruiser Force, and the long run south had not offered any opportunities for the Australia to cut a corner and close. This had resulted in her being a distant spectator initially, watching in futility the ongoing exchanges now nearly six nautical miles ahead. But gradually their initial opponent, the Vonn der Tann at the rear of the German line had begun to steadily drop back, obviously damaged in some way and losing speed.

The long slow approach had been both depressing and disturbing, watching the carnage on the distant line, and for all that another German ship was clearly in distress and also lagging, it was small comfort for the losses seen. As the range dropped to about 15,000 yds the Vonn der Tann opened, fire and a moment later Australia responded, both sides firing only four guns at this range due to the earlier damage. What followed was reflection of the slugging match ahead only conducted on a smaller scale. Learning from the initial exchange, Captain Radcliffe had moved to the Australia's armoured conning tower, trading the limited vision through its slits for the safety of its 10-inches of armour. This proved prudent for by the time the range had dropped, both had hit their opponent nearly half a dozen times, including one stunning hit on the tower itself, which fortunately failed to penetrate. How long this would have continued is unknown when at 1734 the screen attack commenced.

With his ears still ringing from the recent hit, Captain Radcliffe did not at first hear the shout from his signals Yeoman. "Sir, Sir, Termagant's sending a general signal. What is it saying?" he queried. Since the second hit of the action had carried away the aerials along with Australia' rear topmast, Captain Radcliffe had been reduced to flags signals, with no way to restore radio communications. "Sir, Signal reads; Repeat: All ships, General attack - Torpedo." he paused and even as he looked at the lead ship of the three accompanying destroyers, he could see the flags dip in command; execute. As he watched they all began to swing to port, smoke surging from their funnels as they accelerated to close on the Vonn der Tann. With this sight and the briefest pause of consideration, be damned if he had any torpedoes, before he stated loudly to the bridge, "Right…, Bugger this for lark. Let's join the dance." as he gave the order, "Hard a-port coxswain, ships heading to follow the destroyers and close with the enemy." Unknown to himself, even as the shared growl of agreement swept the bridge, he had just forever earned his service moniker. For the rest of his life, the lower decks of Nieustralis ships would refer to him as "Bugger-this Radcliffe" thanks to this moment.

The Australia would close too within 5,000 yards in the following action, receiving a further damaging hit, even as two torpedoes would score the coup-de-gras upon the struggling Vonn der Tann, before circling briefly as the Turbulent and Narborough, the only two survivors of the five escorts involved in their own vicious little melee that the attack on Vonn der Tann had provoked. He could not stop to pick up casualties himself, as the risk was too great for the Australia. Even as he was doing this, he had returned to the flying bridge above the conning tower, not so much to observe the death-throes of the Vonn der Tann, but rather better observe the results of the confused distant action ongoing some miles still to the south as a result of the general attack there. With a spreading cloud of smoke obscuring the increasing disarray of that tactical picture, he needed a better idea of what was happening to decide his next action.

Extract from "Great Sea Battles", William Koening, Abracadabra Press, 1979

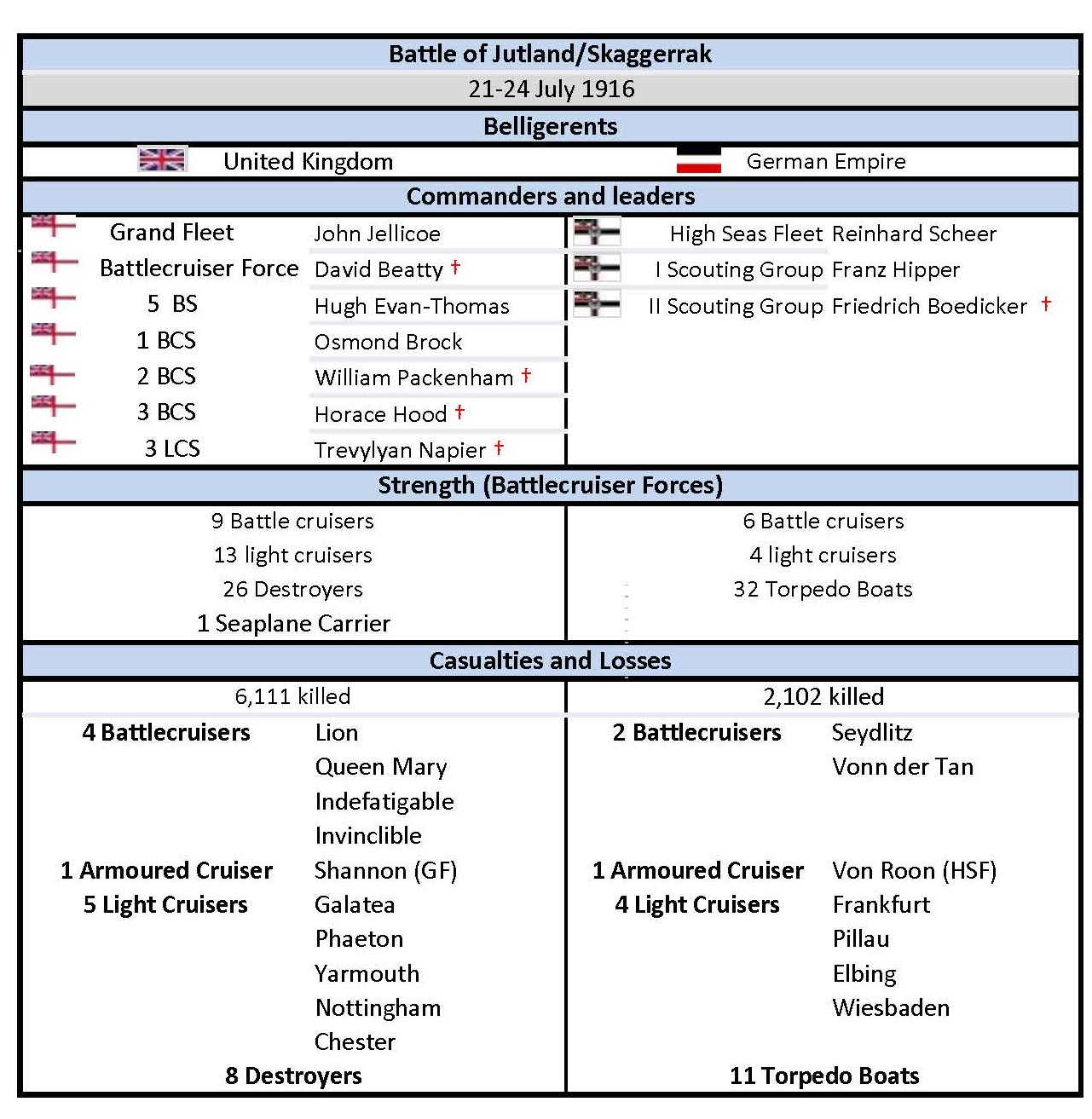

The loss of Admiral Hood and the Indefatigable, would trigger a rapid cascade of actions in a relatively short timeframe and, in concurrence with several external events, cause a major transformation in the whole shape of the battle. Up until this point the action bore a remarkable similarity to naval actions since the days of sail, if only conducted at a range of thousands of meters instead of gunshot. Two forces in single file on parallel courses, pounding each other with fire power to overwhelm the opponent. That the German force despite its fewer numbers getting the better of the exchange being the most notable feature of this phase of the action.

The first trigger to this dynamic change was the launching of a general attack by the British screening force, under the commanded by the senior surviving Flag Officer at that point, Rear Admiral Napier of the 3rd Light Cruiser squadron (3LCS). That this force had been in position ahead of the line, but held by direction for at least half an hour. With the removal of Hood and the Germans now having four battlecruisers to three, was the impetus for his order for a general torpedo attack. This forced the German Screen under Konteradmiral Boedecker to interpose, resulting in a violent confused action between the two lines and significant casualties for both sides, including the screen commanders of both forces. The nature of two screens would have a significant impact on the outcome of the melee. Though more numerous (24 to 18) the German torpedo boats were on the whole smaller and lighter than the British destroyers, with a shorter-range torpedo armament. Both screens had light cruiser support, but here the British significantly outnumbered their opponents, 13 to 4. This factor would be the telling edge that enabled the success of the British attack, with the additional weight of fire enabling the British destroyers to break through, but at great cost. The differing targeting priorities would also tell in this action, with the British screen concentrating on Hipper's battlecruisers while the German torpedo boats prioritised the British light cruisers supporting their destroyer's attack. Though unable to reach the British battlecruisers, the shorter ranged German torpedoes proved sufficient to eventually torpedo and sink four of the attacking light cruisers in their attempts to blunt the British thrust, as these pressed forward to support their own attack.

The final result would be that the Germans would lose all four of the light cruisers in their screen, while the British would eventually lose five, losing HMS Galatea of the 1LCS and its Commodore Alexander-Sinclair to defensive fire and have two more very badly damaged. But this would enable the British destroyers to achieve positions to prosecute their torpedo attacks on the German Battlecruisers. The end result would be a single torpedo hit on the bow of the Lutzow, while the largely isolated and struggling Seydlitz was hit twice, sealing its fate, while forcing the remaining battlecruisers to turn away avoiding the attack.

The timing and rationale of the withdrawal would prove to be of some propaganda significance post battle. That both sides pressed their attacks with great valour and the resultant severity of the action was reflected in the heavy losses on the escorts of both sides. The German losses being eleven torpedo-boats to the British eight destroyers (including the losses in the separate Von Der Tann action). The commanders of both screens would die (Admiral Napier of wound complications some 11 days after the action) along with Commodore Alexander-Sinclair of the British 1st Light Cruiser Squadron (1LCS). By the end of the action of the eight British Flag officers (Commodore Rank or above) who had sailed from Rosyth in the Battlecruiser Force that morning, only Rear Admiral de Brock of the 1BCS on the Princess Royal and Commodore Goodenough of the 2LCS would remain in a position to exercise command at the end of the battle.

Even as this action reached its peak, an event of pivotal significance was occurring some miles to the north of this action. In the initial contact melee, one of the damaged British destroyers in the action, HMS Obdurate, had broken contact and withdrawn before suffering an engineering failure. Damaged and having lost several officers it lagged behind before being forced to halt to repair broken steam lines. At this point it was stationary for over an hour before getting underway again, and had lost contact with the main force. Barely making five knots and unable to chase the Battlecruiser Force, surviving crew later reported that the senior surviving officer, Sub-Lieutenant Clarke, elected to head north to rendezvous with the closing forces of the 5BS, as this provided the shortest timeframe to reach support. Unbeknownst to him this would place the unfortunate Obdurate directly in the middle of the gap Admiral Scheer and the High Seas Fleet was intending to bisect between the two British forces the Zeppelin force had reported. What he may have thought as the full force of German fleet appeared over the horizon can be guessed. Nevertheless, before the German screen would roll over and sank the Obdurate (23 of the crew would be recovered by the German screen) it had sufficient time to radio a sighting report at 1755, detailing for the first time for the British the presence and heading of the main HSF as the enemy force.

This report had a galvanizing effect on the subsequent actions and was the first concrete news the British had received that the full force of the High Seas fleet was out. With this notification, both the Grand Fleet and 5BS, now some 45 and 25 miles respectively north of the reported position, would accelerate to full speed to close on the Battlecruiser Force, now obviously at severe risk of being cut off. For Admiral de Brock, now in command of that force, found himself faced with a number of unpalatable decisions. He would later be best remembered for his earlier remark during the battle to his Flag Captain WH Cowan after the destruction of HMS Invincible, which was to become the iconic quote of the battle. At the time he is said to have turned to his flag captain and said, "there seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today."(6) His Post-action report revealed that his planned intent was to remain in contact, continuing to deploy his three surviving battlecruisers under command to best effect once the results of the torpedo attack by the screening elements were clarified. The news that a major force had interposed itself between his nearest support and was positioned to possibly cut off the withdrawal route of his force and in effect pin it between the two German forces, burst upon him like a thunderclap. The result was that at 1800 he ordered his force to break contact and withdraw on a WSW bearing. His post-action report would reveal a tactically sound justification and his rapid analysis in the heat of battle that his action would avoid it being enveloped between two forces, and that if the enemy pursued, it would in turn expose the High Seas Fleet to the risk of being cutoff if it continued pursuit. What would become of greater significance in following days was the specific timing of this action and the general perception and propaganda value that resulted.

For Admiral Hipper, the immediate threat was the impact of the developing British torpedo attack which threatened to overwhelm his own screen and the damaged capabilities of his own large ships to effectively defend against this. Postwar analysis would reveal he had ordered his forces to disengage and turn away at the almost identical time as Admiral de Brock. In event the main German line would not visibly turn onto an ESE heading until 1805, a gap of several minutes after the British. Beyond the impact of torpedo hits on Lutzow and Seydlitz, for propaganda purposes the delay would play a distinct role in the public perception of the engagement in the subsequent aftermath.

At this point it is necessary to remember that the Lutzow, Hipper's flagship, had already taken a tremendous pounding in receiving over 25 large-calibre hits, several very recently, yet was astonishingly still at the head of the formation and maintaining a speed of twenty knots. The scale of damage had resulted in general destruction of much of the upper works, including aerials, signals halyards and lights. Wireless telegraphy was in use, though their fragility and the limitation of the radio sets made their extensive use more problematic particularly in this extreme situation. Thus, most command signals were made with flags or signal lamps between ships, with the flagship was usually placed at the head so its signals might be more easily seen by the many ships of the formation. It could, even in the best of circumstances, (which this clearly was not), take a time for a signal from the flagship to be relayed to the entire formation. In a large single-column formation, a signal could take 10 minutes or more to be passed, with limited visibility from smoke on top of battle damage acting to delay the probability that a message would be quickly seen and correctly interpreted. In this case, that it was actioned in this time frame would likely indicate that both commanders had given the command to turn away virtually simultaneously, with the battle situation delaying its implementation far more noticeably for the Germans.

This disengagement would mark the end of the major surface action between combatants for the action, though a number of significant events would still occur.

1828 22 July 1916, SMS Friedrich der Grosse; Flagship HSF, North Sea

As the report of the encounter with a British Destroyer arrived and his own transmission office on his flagship confirmed news of it radioing his location, Scheer found himself grimacing. Jellico would now know he was out and his location. He had hoped for another half-hour to get even further west and improve his position to isolate Beatty's force but so be it. He was in a position to trap a portion of the Grand Fleet at all, and while not an optimist by nature, he could now come to Hipper's support, trapping the British between his two forces. With Zeppelin's reports providing an accurate idea of his opponent's location and size, he gave the order to for the High Seas Fleet was change heading to the south west behind the British and increase speed to its maximum 21 knots. With the battlecruiser force cut off it was almost certain that the five reported dreadnaughts to his north would engage his force, even with an open withdrawal route available. No Royal Naval commander could not help but move to the sound of the guns, especially when it was to support a hard-pressed compatriot. He had placed his heaviest hitters in his northern column of his force to engage such a response. With his own strength of numbers and ideal situation was developing to destroy a significant portion of the British Grand Fleet elements involved, and reward the sacrifices of Hipper's force.

All these considerations would be rendered mute at 1803 when his communication officer, scrambled onto his bridge with the news he had subtlety been dreading all day arrived. The Grand Fleet, with thirty plus dreadnaughts, had been sighted by Zeppelin L-17, position some 40 miles to the north and closing. This report was to prove a pivotal turning point, not only in the immediate tactical situation, but its eventual long-term impact on the wider scope of naval actions in the war. The Zeppelin force had been critical in its provision of reconnaissance reports, providing Scheer a much more accurate tactical picture of the location of the British forces, whilst the British had largely remained in ignorance of anything beyond direct visual distance. This had enabled Scheer to deploy his forces to reach the position it was in, poised to attack, when at long last one of the airships located to the north for just this reason sent an electrifying sighting report. The news that the entire Grand Fleet was out, with a far greater dreadnaught strength than his own, was barely 40 miles distant and closing was a blow to the gut of Admiral Scheer.

Facing an agonizing decision, Scheer would maintain this course for another eight minutes, confirming details, and receiving an update on the status of Hipper's forces. Also reported, the presence of a battlecruiser and light forces some miles closer to the north of the British battlecruiser force. This was in fact the Australia, now well separated from the main body of the remaining BCF and some elements of the dispersed screen that had joined it in the aftermath of the torpedo attack. The news of the loss of two of Hipper's force, and that it was withdrawing with damaged ships slowing it, forced him to accept the unpleasant realities now facing him. Even as the mastheads of the 1st Cruiser Squadron ahead of the 5BS, appeared over the horizon, he reluctantly accepted that the opportunity for victory, so tantalisingly present a brief few moments before, was now receding and gave the order for the High Seas Fleet to turn away.

Far beyond the immediate reality of turning to the south-east and being in a position to cover the withdrawal of Hipper's damaged and struggling force, this was to prove the decisively pivotal moment for the conduct of operations between the two navies for the remainder of the war. While conforming to the spirit of the Kaisers directive to preserve the fleet, it also came to represent recognition that the High Seas Fleet was simply not strong enough to confront the full force of the Grand Fleet in a direct engagement. The long-term implications for the morale of the High Seas Fleet were little realized at this time, but the effect of turning away at the very moment the enemy came into sight was to be profound.

Postwar analysis of his diary and correspondence interestingly revealed how stricken he was by this decision, recognizing the significance of this moment and that it was the report of the lagging Australia group which was the final influence on his decision to avoid action. He would write of this shortly after, likening it to 'some wounded lure trailed in front of my face, in order to entice me to combat.' Unable to contact Hipper aboard Lutzow and unaware that Hipper flagship was no longer capable of receiving radio communication. He was aware his ships would have sufficient leeway to make their own escape, provided he was not required to shepherd slower elements back to the Jade. For this reason, he would skillfully reposition his own screen during withdrawal to be able engage any attempt by the 5BS, now distantly visible on the horizon and intent on closing, to engage and create stragglers for the Grand Fleet to catch in pursuit. Evan-Thomas did close to visual distance but lacked sufficient screen of his own to oppose the size of Scheer's light forces interposed and prudently elected not to press the pursuit. Once Australia and the remaining battlecruiser forces consolidated some 20 miles to the west, would join them later that evening as they withdrew.

For Hipper, the withdrawal was to prove far more challenging. During the torpedo attack that forced his turn-away, his screen had laid smoke to obscure it. This proved largely effective but for the two vessels at the head and rear of the line, Lutzow and Seydlitz.

This smoke proved of scant assistance to the badly lagging Seydlitz. By this stage Seydlitz had been hit 21 times by large-caliber shells and had no main armament operational, and already suffered over 150 crew killed or wounded. Moving now at less than ten knots, she was in a critical condition; having already been flooded with over 5,000 tons of water, and the bow was nearly completely submerged. Only the very calm sea state and buoyancy that remained in the forward section of the ship was the broadside torpedo room keeping her afloat. Even as the attack had developed preparations were being made to evacuate the wounded crew. Exposed and a sitting target she would take two torpedoes' hits forward, destroying what little hull integrity and buoyancy that remained. Clearly doomed the order to abandon was given, and Torpedo-boats G42, and G85 came alongside to evacuate casualties and the crew. With remarkably little fuss, she would soon join the Vonn der Tann, slowly dipping her bow below the waves and finally disappearing at 1857, the last of the capital ships lost this day and taking 333 of her 1,072 crew with her.

Being at the head of the German line Lutzow had been trading fire with the heaviest armed of their British opponents for the entire action, and had suffered accordingly. By the time the British torpedo attack had commenced she had been hit 24 times by British heavy-caliber shells. In particular during the preceding 20 minutes, Lützow was struck in quick succession by four heavy-caliber shells. One pierced the ship's Bruno turret and disabled it. The shell detonated a propellant charge and the right gun was destroyed. The second hit jammed the training gear of the Dora turret, while the remaining two struck midships, damaging the engines, and removing Hipper's ability to communicate with the squadron. Up until now the Lutzow amazingly had still been moving at 20 knots despite its previous damage, but now began to lose speed. With British destroyers sweeping in, V45 and G37 began laying a smoke screen between the battered ship and the British line, but were unable to prevent several from launching torpedoes. At this point Lutzow had been turning away already, and all missed ahead except one which struck the bow, just ahead of the start of the armoured belt.

With his flagship losing speed and was unable to keep up, combined with its inability now to communicate, Hipper elected to transfer his flag and G39 came alongside and took Hipper and his staff aboard, in order to transfer him to the next in line Derfflinger. Lützow had fired her last shot in the battle, and the smoke screen had successfully hidden her from the British line. By now its situation was remarkably similar to that of the Seydlitz earlier, speed dropping to reduce the pressure of the inflow as flooding in the forward part of the ship reached dangerous proportions.

The main difference was the greater buoyancy margin as Lutzow unlike the Seydlitz had not already been flooded with several thousand tons of water. As the other three ships withdrew to the southwest Lützow was steadily settling deeper into the sea. Only the developing mirror like calm of the sea was preventing waves washing onto the deck and into the forecastle. At midnight, there was still hope that the severely wounded Lützow could make it back to harbor, with the ship down to 7 knots with over 4,000 tons on water now on board. Only the continued operation of the forward main pumps was keeping the inflow in check.[7] Lützow was so low in the water by that point that the rare low swell would increasingly wash all the way over the deck up to the forward barbette. This caused water to enter the ship through the numerous shell and shrapnel holes in the forecastle area, and slowly worsening the flooding. Counter flooding was required as the bow became so submerged that the propellers were pulled partially out of the water and forward draft had increased to over 17 meters. So much water was aboard that she scraped over Horns Reef shortly before dawn, and reached the outer Jade River on the morning of 23 July. Such was the critical condition with the bow nearly completely submerged, and flooded by well over 5,000 tons of water, that there was great danger of capsizing. She was saved only by the timely arrival of a pair of pump steamers that were able to stabilize the flooding. On 3 July the ship entered Entrance III of the Wilhelmshaven Lock in what was a truly outstanding display of damage control by its crew. Not only was this a tribute to their extraordinary efforts, but also one to the fundamental toughness of its design. Despite this survival she had still suffered nearly 200 casualties in her crew, and the damage as so extensive that she would not return to service for nearly a year. The withdrawal of the battlecruisers would mark the end of the battle, and once aboard Derfflinger, Hipper transmitted a report to Scheer informing him of the tremendous damage his ships had suffered. By this time, Derfflinger, Hindenburg, and Moltke each had received over 20 large calibre hits, only had one or two turrets in operation, Moltke was flooded with 1,000 tons of water, and whilst all were remarkably still capable of 15-17 knots, Hipper reported: "I Scouting Group was therefore no longer of any value for a serious engagement, and it is my intent to return to harbor unless otherwise directed by the Commander-in-Chief." Scheer himself while following the withdrawal of the I Scouting Group, determined to await developments off Horns Reef with the battlefleet.

The final incidents of the engagement, beyond those revolving around the withdrawal of the damaged vessels and recovery of wounded and survivors of both sides, would be remarkably similar and due to the action of submarines. Acting as part of the gatekeeper force at the mouth of the Jade River the German Armored Cruiser Roon would be torpedoed and sunk by the submarine E-24 midmorning of the 23rd, causing Scheer to rethink his plans to linger. In much a similar fashion the Grand Fleet would lose the Armored Cruiser HMS Shannon approaching Scapa Flow late that afternoon, a victim of U-27. The final ship involved in the action to successfully reach harbor would be the British destroyer Pelican, with her bows blown off. Towed backward she would reach harbor on the 24th, marking the conclusion of the naval portion of the battle.

6. IRL this line was actually attributed to Vice-Admiral Beatty who is said to have turned to his Flag Captain Chatfield and said it immediately after the destruction of HMS Princess Royal.

7. Though severely damaged IRL the Lutzow had successfully withdrawn and was returning to Kiel under its own power, when critically, the forward main pumps became unusable, as the control rods jammed. This allowed unchecked flooding and the loss of buoyancy forward, which caused the bow to became awash, increasing the rate of flooding and eventually forcing the ship to be scuttled. Post-action damage reports suggest that had the pumps not failed then it was very probable that the Lutzow would have survived in a manner similar to that of the Seydlitz, which likewise had suffered extensive flooding forward but kept its pumps working and retained some forward buoyancy despite the flooding. This failure does not occur ITL and despite the damage Lutzow survives.

1736, 22 July 1916, HMS Southampton, North Sea, 220 miles from Rosyth

Rear Admiral Napier was quite happy wearing two hats, being both the commander of the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron, and senior officer commanding the entire screen of the 1st BCF, which in effect totaled 13 Light cruisers and a total of 24 destroyers. In the months of his command, they had drilled and worked together, and the challenge represented one of the most satisfying periods of his life. But all the preparation and training in the world had become victim of the other great timeless navy truism, no plan survives contact with the enemy. Quite frankly as commander of the screen he was having a bad day, and his sour mood at the moment reflected it.

From the moment of the contact with the extreme edge of the screen events had seemingly conspired to create factors to disorganize his screen. The initial contact had collapsed the ships on that flank towards the fight, and the vicious little engagement had further disorganized the sections involved. By the time both sides had broken contact he had not only lost a destroyer, but the dense low smoke and rapid interplaying of small ships in melee had broken the formations up, not to mention causing damaged ships to fall out of action. This followed by the Battlecruiser force reversing course and then the second course change by Beatty had left the vast majority of the screen badly out of position, trailing the battle line instead of being ahead to do its job, and be best positioned to intervene for defence or attack. With only a few knots advantage it had taken far too long for the screen to regain a leading position, not helped by receiving the order "Destroyers clear the line of fire!". This had basically forced his ships to essentially follow three sides of a square in regaining the lead whilst moving up the western disengaged side of the battleline. Then firstly the Australia being forced out of the line, followed unbelievably by the loss of three battle cruisers, had obliged him to leave ships in each case for support or rescue duties.

Finally, barely half an hour ago, he had mustered the remaining balance of his screen and was in a position to attack at last. Looking through his glasses he could see the forces of the enemy screen in the van of their formation. These were the ships that he would engage, and in his mind, was assessing what he was seeing. Even having left ships to support stragglers, there still remained well over twenty torpedo boats there. Individually smaller and more lightly armed than his ships, he had only about 3/4 of his original destroyer force in hand. More powerful individually but offset by their number it would be a roughly equal battle. What he had was his three squadrons of light cruisers, and to his eye there where at most 4-5 to oppose his baker's dozen. This was the hammer to crack the defense, and if he committed his entire force then he was sure that he could get two or three of their big ships if he employed the screen en-masse.

Increasing further his foul mood, carefully hidden behind his calm exterior, his professionalism was battling with a profound dissatisfaction. Partly this was the events of the day, the screening issues and the losses already suffered, and partly was his current inactivity. He could see the enemy, and was in a prime position to inflict damage on them, but Admiral Hood had ordered him to wait for now. He could only watch and wait in anticipation, and could feel the anger and eagerness on his bridge. The Royal Navy as an institute was not used to coming off second best, and for all that events had not gone their way to date, He was certain that there wasn’t a single matelot in the screen who wasn't eager and champing to reverse that fact. This intense focus was snapped abruptly by an aghast call, "Sir, the flagships blown up." Causing him to spin around in shock once more, to confirm with his own eyes despite his disbelief. For some 30-40 seconds he just stood, staring, initially too surprised in conflicted disbelief to organise his thoughts coherently at first, before the logical portion took control and recognised that he was now the one in the box seat, scanning the disrupted battleline behind and the visible dispositions across to the enemy. The chain of command was clear in the Battlecruiser force, Rear Admiral de Brock was in command of the 1BCS, now reduced to the sole ship, HMS Princess Royale at the head of the line, and was his junior. While controlling the Battlecruiser force, his promotion was only recent and up until May 1915, he had actually been the previous Captain of Princess Royal itself.

Overall command was now his, and experience and professional instincts made him pause for a further moment, analyzing if it was workable or just his instinct to lash out at the losses endured, before after a brief nod to himself, turned to his flag Yeoman on the bridge of HMS Falmouth and said, "Get a radio signal out to the Grand Fleet and 5BS with an update and advice I am attacking." Evan as he could hear the growl of approval from those around him, he added, "General signal to the screen, all ships: general attack - torpedo," and added as an aftermath to the surrounding bridge personnel, "Let loose the dogs of war," with a tight grin.

1742 22 June 1916, Skagerrak, North Sea, 250 nautical miles from Rosyth

Konteradmiral Friedrich Boedecker’s IInd Scouting Group had reformed ahead of the Hipper's battle cruisers fairly quickly after the initial contact melee at the start of the action. This job made easy by the few heading changes during the slugging match that had developed between the capital ships of the two forces behind him. He had been forced to detach several of his torpedo boats to provide support for the lagging Vonn der Tann and Seydlitz, but still had over two dozen available in support of the four light cruisers under his command. He had watched with increasing foreboding as the British screen had steadily reformed ahead of their line opposite. For the last half an hour or so they had just paced his own forces, visible across the dozen kilometres separating them, and he could see they had three times the cruiser force he had, just hovering forbiddingly. For all he had an edge in numbers of smaller vessels, he was at a loss as to why they had not attacked before now. Even the most partisan of officers of the Imperial German Navy had never accused the Royal Navy of timidity, and the longer he had studied the serried lines of cruisers and destroyers shaken out opposite him, the greater the tension had built in his own mind, simply waiting for them to act. When they did, he knew his own forces were going to be stretched to the limit to respond, and the analytical part of his training already indicated that the odds would be badly against him. The destruction of a fourth enemy battlecruiser was a passing distraction, preoccupied as he was with anticipation of whatever the opposing screen might do. So, when at 1754, he saw the entire leading force swinging in to lunge towards Hipper's ships it actually came as a relief from the rising tension. Even as he was giving the orders to martial his own forces to counter attack and interpose themselves between the lines. A distant small distracted part of his mind, briefly mused if the delay had been deliberate, simply to evoke the tension felt before committing to attack, as he and the ships and men under his command steeled themselves for what was undoubtedly going to be a bloody and brutal confrontation. This distraction was lost as the first shots began arriving and he committed himself fully to the chaos of battle unfolding.

1741, 22 July 1916, HMS Narborough, 13th Destroyer Flotilla, North Sea.

LT Reginal Barlow was still a comparative rarity in the RN, being a Royal Naval Reserve officer from P&O and not a regular, and now acting as an Executive Officer on a M-class Destroyer. Having initially been a freshly appointed 3rd officer on the British India Steam Navigation cargo-liner Bankura in 1913, he had followed the practice of most of British officers of the major Royal Mail Ship navigation companies by joining the Royal Navy Reserve. He had made only a single cruise to Asia by 1914 when the company had amalgamated with P&O, and on the outbreak of war volunteered to serve with the tacit encouragement of his employers. Initially posted as a Sub-lieutenant to a destroyer of the Harwich Patrol and had found he thrived in the active role, despite the hard lying conditions. His basic competence and youthful enthusiasm for the job had seen him promoted to LT, and by early 1916 he was posted as exec of the Narborough. Initially part of the Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow he had found the lack of action, not to mention the freezing cold, incredibly boring and had thrown himself into his job. Fortunately, in May Narborough was transferred to the 10th Destroyer Force to be part of the screen of the Battlecruiser force based out of Rosyth, much to the pleasure of both himself and the rest of the ship's crew.

The day had initially looked like being a repeat of the earlier uneventful May sortie, up until shortly after noon, when a sighting of smoke to the east by Obdurate, one of the Narborough half-section had triggered a brief but confusing action with a number of German torpedo boats. Last ship in line, Narborough had followed its three sisters into action, with 'Reggie' in his usual action station with the rear 4-inch gun.

In the subsequent brief but fierce action, charging through a confused melee in the low obscuring fog of smoke, left by the wild interweaving of ships in the largely calm conditions, she had become separated from their companions. In the midst of a flurry of sudden short-range exchanges as ships appeared and disappeared at random, whilst trying to identify and engage targets, he had heard a detonation forward and felt a sharp shudder underfoot, he knew the ship had been hit as it suddenly veered sharply away to port. Leaving the gun to the mount petty officer in charge, he was rushing forward and fearing the worst when he was met by a runner at the forward funnel, with the news that the bridge had been hit and the captain was down. He arrived to find three still bodies and learned that a small calibre shell had burst directly under the tiny bridge causing casualties and disabling the forward 4-inch mount. By the time he had regained control the ship had already completed two full circuits through several bands of smoke and he found he had no idea where he was or the location of the rest of his half-section or the enemy. Still moving at over 25 knots and peering ahead he thought he could see a ship ahead heading east and, thinking it most possibly one of their own followed it. Only a few moments later they burst out into clearer conditions, and to the sudden realisation that they were taking station at the rear of a line of three or four German ships just a few cables ahead. The abrupt reversal of their course rapidly back into the smoke had also awoken the Germans to the fact that Narborough was not one of their own, and it was pursued by shells as disappeared back into the mirk.

After breaking north and then back west for some minutes the Narborough had emerged some quarter of an hour later to find itself in seeming isolation with startlingly not another ship in immediate sight. With his radio destroyed, and only a generalised idea of his location, he elected to follow the distant smoke cloud on the horizon to the south. As they closed on the smoke it resolved into another ongoing action, eventually revealed as the battlecruiser Australia, accompanied by two destroyers, exchanging fire with a German battlecruiser, also with a pair of escorts. Challenged by HMS Turbulent his response had been the ships number followed by: "Captain dead, no Comms, permission to join." With the brief confirmation, Narborough had fallen in behind the trailing HMS Termagant, and for the next period of time the three had acted as screen to the Australia, whilst being spectators to the slow relentless exchange as both battling ships were each hit several times, damage increasing and guns falling silent. At 1755 he saw the signal run up the Turbulent mast, "General Signal: Torpedo attack, conform." flying for some seconds while its two companions acknowledge, then with the dip of execute, all three turned towards the distant Vonn Der Tann.

On the bridge of Narborough, despite the mute evidence of the silent gun on the foredeck before him, Barlow felt an intense excitement at being in command as his ship drove forward to attack the enemy battlecruiser. The larger and faster T-class ships ahead of him slowly opened a slight gap and he could see two German ships curving to intercept their thrust short of its target. With events developing rapidly as the ships closed, he altered Narborough’s heading slightly to use the others funnel smoke to mask his own approach, as the guns of the five converging vessels were firing rapidly as the range shortened. Even as this was happening, he caught the surprised report from his signalman, "Australia's also closing sir!" A quick glance over his shoulder confirmed that the battlecruiser had also swung to port and was now acting like some oversized destroyer, charging on a sharply closing bearing to the limping smoke shrouded German ship ahead. With a wild laugh he couldn't help but respond, "The more the Merrier, flags!" before concentrating on the task in hand. Ahead he could see first one, then a second hit on the Turbulent, and the flash of another on the Termagant, but perhaps, due to the smoke and separation, for the moment no one seemed to be actually firing at the wildly charging Narborough. His own guns, their arcs opened by the course change, were now firing as well, and he nodded with satisfaction seeing a flare blossom on the lead Torpedo boat. Again, his ship seemed to be enveloped in a brief shroud of concealing funnel smoke, before suddenly breaking into the open exposing a plodding, Vonn der Tann, broadside on and hardly moving at less than 10 knots, "target Battleship to Port, engage as bearing, He shouted out to his sole Sub-lieutenant now at the tubes. "Hard a-starboard he ordered the Coxswain, as the range dropped to under 4,000 yards, clinging to the bridge screen as the ship heeled sharply with the radical turn. For the first time the Vonn der Tann seemed to recognise its threat and one or two of its secondary armament began throwing shells in their direction, but too few and far too late. As the ship swung upright, he could hear the thump one after another as the four torpedoes leapt into the water. Even as another radical turn sought to escape danger, his eyes remained rivetted on the target. At first nothing as the ship ploughed on seemingly unaware of its danger, but finally sluggishly it seemed, he could see a slight bearing change of its bow as it sluggishly began to turn. Unconsciously he found himself softly muttering, "Come on…, come on…," until unbelievingly first one then another huge spout arose from the Vonn der Tann's stern quarter. "Yes!" he couldn't stop a jubilant bark, and giving a brief un-officer like hop, before getting himself under control, then realising it had been lost in the general crowing, as an equally joyous roar of euphoria swept his ship, even as it began wildly changing course in withdrawal. His successful actions during the day would subsequently earn him a DSO and ensure him senior command with P&O in the future, and unbeknown to him eventually a carrier command in the Second World War.

1744, 22 June 1916, SMS Von der Tann, North Sea,

Kapitan zur See Hans Zenker, Captain of the Battlecruiser Von der Tann had long known is beautiful ship was increasingly in trouble. Laid down in 1907, she represented Germany's first attempt at designing a ship to meet the modern battlecruiser concept. Her very success and durability reflected the intensity and amount thought that had gone into the initial work to conceptualise her design. But despite this success she still represented the oldest and smallest of the modern German battlecruisers, being barely two-thirds the size of later ships. So, despite the excellence of her design, she still simply lacked the mass to absorb the degree of punishment of the others and was the most susceptible of the to the steady accumulation of damage inherent in any long slugging match.

The action had started well with the rapid and effective fire initially knocking an Indefatigable class ship out of the line, if only temporarily as it occurred. But despite continued hits on the opposition, the simple fact that she occupied the tail position against more numerous foes, ensured that multiple opponents engaged her when she could only effectively reply to one. The British ships had each picked an opponent at the start of the action, but that had translated into initially three ships and later two in the British line all firing at his own. By the time the destruction of two Royal Navy heavy ships, had reduced it to a one-on-one contest, the Vonn der Tann had already suffered significant damage as a result. At this point his ship had now been hit 12 times, with Both Anton and Dora turret on the disengaged side out of action. Anton turret was burnt out from a direct hit. Dora turret had been penetrated through its thin rear armour and thought the shell had failed to detonate it had killed or injured most of its crew and the shock from a shell impacting the barbette had jammed it. Bruno turret on the engaged side had suffered damage to one recoil mechanism, whether due to a near miss or the simple shock of the ship firing its main armament so regularly was not known as yet. She was down to two turrets, one firing at reduced rate, and both firing under local control as another hit had destroyed the main rangefinder.

Another shell from the same salvo that had wrecked Dora turret had impacted the after funnel and causing the ship to lose speed. For a while it had dropped out of engagement by an opponent. But as it fell further back, separated from Hipper's main battle line, it found itself once more exchanging blows with the Australia, similarly lagging from the British line due to its earlier damage. Again, hits began to accrue and despite his crew’s best efforts to keep her in action. Everywhere it seemed, a struggle against the incursions of fire and water was being waged. A shell had pitched short near the stern, flooding an after-boiler room and filling the ship with hundreds of tons of seawater. By now her speed was down to less than fourteen knots and reducing further as she wallowed deeper in the water. She had struck her opponent at least five times in the most recent exchange as the range had reduced leaving her afire in two places but in turn lost Bruno turret, so now only Caesar, the aft turret continued to fire back. Her opponent, while continuing to burn fiercely aft, never ceased to return fire with regular reduced four-gun salvo's. Captain Zanker now feared the worst but would continue to fight back while he effectively could regardless.

At 1745, shortly after another eruption in the distant ongoing exchange ahead, what he feared most came into reality. Suddenly he could see destroyers bearing down on his struggling ship, obviously intending to attack. Even as the two accompanying torpedo boats V248 and V189 moved to interpose, he could see the Australia, also now swinging about to close. With few of his secondary guns still in action, and all her former lithe speed robbed, he knew what was about to happen. Even as he spied a new threat emerged from the smoke, Von der Tann suffered yet another hit from the closing Australia that fully detonated against the base of the rear funnel. Her deck, already weakened by the earlier hits and unarmoured funnel, partially collapsed into the hole, and forcing the crew out of the machinery spaces. Even as the ship lost power, he could see the destroyer launched threat closing. Despite her helm being hard over and her bow swinging oh-so-slowly, he knew the effort would prove futile. First one, and then a second struck her after quarter, sending mast height spouts into the sky and penetrating the hull. Already Lamed and with an enormous cloud of smoke emanating from her, her shafts warped and rudder jammed she now slowly sagged to port as she coasted to a stop. As hundreds of tons of additional water now surged into the gaping holes below her waterline, she steadily began to list to starboard, her stern obviously rapidly filling. Without power to fight the flooding Zenker gave the inevitable order to abandon ship and with her guns now silent, her crew commenced to swarm upon deck, casting buoyant objects into the calm seas as she slowly coasted to a halt. Nearby, both her escorts also succumbing after their futile efforts at protection, would be soon joined by HMS Termagant in sliding below the waves.

With the command "All hands. Abandon ship" given at 1816 it was all Kapitan zur See Zenker could do was watch and await the final plunge of his beloved Von Der Tann. Already he could see that the Australia had ceased fire and was circling at a distance, topsides now sparsely crowding with observers despite a still smouldering fire in its stern superstructure. He stood contemplating as crewmembers took to the water as the remaining two British destroyers closed in to recover survivors of both sides. There was nothing more that could be done here he sighed; his ship had fought to it's last. No ship built of metal could withstand such an onslaught, yet Vonn der Tann had for so long. For all that, there were limits and it was now time to save his brave crew, that integral ships portion not made of metal. They had done all that could reasonably expected and more, and whatever the result of the action it was time to ensure the escape of as many as possible. It was to take nearly a further half hour before standing soaked on the deck of HMS Narborough, tears streaming unnoticed down his cheeks and surrounded on its massively over-crowded deck by recovered sailors all watching the final moments of his lovely command. Ever lady like she had briefly straightened upright before settling slowly stern first before finally slipping with little fuss beneath the surface of the North Sea, taking 303 of her 923 officers and crew with her.

1742 21 July 1916, HMNS Australia, North Sea

Despite its best efforts it had proved that the Australia had lacked the necessary knot or two or speed to successfully close with the rest of the Battlecruiser Force, and the long run south had not offered any opportunities for the Australia to cut a corner and close. This had resulted in her being a distant spectator initially, watching in futility the ongoing exchanges now nearly six nautical miles ahead. But gradually their initial opponent, the Vonn der Tann at the rear of the German line had begun to steadily drop back, obviously damaged in some way and losing speed.

The long slow approach had been both depressing and disturbing, watching the carnage on the distant line, and for all that another German ship was clearly in distress and also lagging, it was small comfort for the losses seen. As the range dropped to about 15,000 yds the Vonn der Tann opened, fire and a moment later Australia responded, both sides firing only four guns at this range due to the earlier damage. What followed was reflection of the slugging match ahead only conducted on a smaller scale. Learning from the initial exchange, Captain Radcliffe had moved to the Australia's armoured conning tower, trading the limited vision through its slits for the safety of its 10-inches of armour. This proved prudent for by the time the range had dropped, both had hit their opponent nearly half a dozen times, including one stunning hit on the tower itself, which fortunately failed to penetrate. How long this would have continued is unknown when at 1734 the screen attack commenced.

With his ears still ringing from the recent hit, Captain Radcliffe did not at first hear the shout from his signals Yeoman. "Sir, Sir, Termagant's sending a general signal. What is it saying?" he queried. Since the second hit of the action had carried away the aerials along with Australia' rear topmast, Captain Radcliffe had been reduced to flags signals, with no way to restore radio communications. "Sir, Signal reads; Repeat: All ships, General attack - Torpedo." he paused and even as he looked at the lead ship of the three accompanying destroyers, he could see the flags dip in command; execute. As he watched they all began to swing to port, smoke surging from their funnels as they accelerated to close on the Vonn der Tann. With this sight and the briefest pause of consideration, be damned if he had any torpedoes, before he stated loudly to the bridge, "Right…, Bugger this for lark. Let's join the dance." as he gave the order, "Hard a-port coxswain, ships heading to follow the destroyers and close with the enemy." Unknown to himself, even as the shared growl of agreement swept the bridge, he had just forever earned his service moniker. For the rest of his life, the lower decks of Nieustralis ships would refer to him as "Bugger-this Radcliffe" thanks to this moment.