November 1918 – Europe and the World after the Great War (a quick authorial overview)

Most prominently in Europe, but also in other parts of the world, the intense relief felt by the population after the Great War had finally ended on October 19th was slowly giving way to an atmosphere of confusion.

Late October and November 1918 was when the deadly second wave of the Spanish Flu washed over the continents, killing millions of people. It was also the time of other, much more ambiguous, and sometimes outright enthusiastic waves: universal suffrage was being legislated or applied for the first time in the United Kingdom [1], in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Italy [2], Poland [3], Romania (and Uruguay, even though remote from the events of the Great War). A first wave of soldiers returned home, scarred by their experiences in the Great War. Worker and peasant unrest rocked Germany and Yugoslavia – a phenomenon which would spread to other peoples in the months to come, as more and more demobilized soldiers returned into an economy hit by destructions, horrendous public debts, and in full conversion from war to peace production. Surging nationalism created tensions involving Germans and Poles, Poles and Lithuanians, Croats and Serbs, Hungarians, Slovaks, Serbs, and Romanians, Greeks and Turks, Estonians, Latvians and Baltic Germans, and many others.

Early in the month, in elections to the House of Representatives and the Senate, US President Woodrow Wilson’s Democratic Party narrowly lost control over both houses of Congress [like OTL]. Nevertheless, Wilson’s administration remained intensely engaged in preparing the ground for peace negotations, which were planned to begin in December in Paris, as well as in attempting to prevent the Europeans from jumping at each others’ throats again.

The latter was a gig+antic task indeed.

The newly established State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, who sought unification with the Kingdom of Serbia, for example, was confronted with massive popular resistance against unification under the Djordjevic dynasty in parts of Croatia and Bosnia, where the rebels included armed and experienced men from the Green Cadres. The nascent SHS state was still weak, but to its luck, its opponents were plagued with internal divisions, too: a “Democratic Yugoslav Committee” under Stjepan Radić fought for a democratic and federal Yugoslavian republic, which would include at least Bulgaria, too, and possibly even Albania, while other rebel groups preferred an independent Croatia, with some of the latteri favouring a monarchy and others a republic. The rebellious peasantry sympathized with revolutionary Narodnik ideas about land repartition, while groups affiliated with the Catholic Church were much more conservative in nature and abhorred the idea of the “Russian virus” spreading to Southern Slavic lands. As a consequence, the forces loyal to the SHS National Council, aided by Serbian detachments and tacitly by the British and French units present in the region, too, began to gain the upper hand in the chaotic situation of violent streetfighting which haunted the larger towns of Croatia by the end of October. The anti-Pašić rebel coalition received far less foreign support – both the Union of Equals and the new Bulgarian Republic viewed the agrarian revolutionaries and socialists among them with great sympathy, but the geographical presence of Serbia between them and Slovenia-Croatia-Bosnia prevented them from providing any significant amount of concrete support which went beyond diplomatic protests against the “bloody oppression of democratic expressions of national self-determination”. The Italian government, on the other hand, began to quietly ship support to radical Catholic groups in Croatia in late October, but this was barely enough to prevent their total annihilation. Thus, the rebels were not defeated – they still controlled great parts of the countryside –, but they were driven into the mountains, from where they would continue their fight, from mid-November finally at least formally united in a counter-“Mostar government”. On the diplomatic stage, the Mostar government’s stance was not too promising, either: While the Union of Equals’ Foreign Commissioner Axelrod emphatically spoke out for the right of all South Slavs to determine the shape of their future state in a grassroots, bottom-up process of nation building, Britain and France insisted on the framework agreed upon in the Corfu Declaration, and while the US position was less determined yet and more of a vaguely pro-Yugoslavia stance, Secretary of State Robert Lansing had already made it clear that it would be unacceptable to the US if the defeated Central Power Bulgaria had a say in the process of its formation. Throughout November, Axelrod was forced to increasingly moderate his criticism, though, in order not to risk the loss of credibility of the UoE’s foreign policy with the pursuit of contradictory policies in the Yugoslav and the Polish Questions [see more below, or rather: tomorrow, when I’ll have finished the part on Poland].

Under these circumstances, the SHS National Council in Zagreb announced on November 28th that elections for a constituent assembly for a unified Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, which would encompass the formerly Habsburg SHS territories as well as Serbia and, if things went well, Montenegro, would be held in late January. Two days later, the Mostar counter-government announced to hold rivalling elections to “Federative Republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina” (envisioned to become part of a greater Yugoslav federation one day) a week earlier.

These events represented the first foreign policy failure of the young Bulgarian Republic. Its governing coalition of the agrarian BANU and various Social Democratic parties, headed by the People’s Supreme Commissioner Alexander Stambolinsky, was more successful with its domestic reforms, though. Village committees were reformed to oversee and implement the agrarian reform which the revolutionary Commission had decreed, and workers’ councils were forming everywhere and endowed by the government with far-reaching powers to manage the conversion of the country’s wartime economy to peace production – a gigantic challenge which met, at every step, with protests and attempted obstructions. The dire state of food production and distribution as well as the overstrain of the country’s medical services faced with yet another pandemic wave further contributed to a general state of turmoil. The continued presence of UoE Republican Guards in the country helped calm the situation, though, and allowed Stambolisnky’s government, whose security forces were in a process of disintegration, to steer through the troubled revolutionary waters without being overthrown, slowly building up alternative security structures based on the agrarian and proletarian parties’ Orange and Red Guards. As the government reasserted its control over key public services and the danger of counter-revolution appeared to wane by the end of November, it became increasingly clear that the revolutionary coalition of the BANU, the Wider Socialists and the Narrower Socialists would not stay together for much longer. The divergences between Dimitar Blagoev’s Narrow Socialists, who hoped to unify all radical revolutionary socialist parties of the wider Balkan region, clamoured for widespread confiscations and immediate nationalization of all industries as well as for the formation of voluntary proletarian corps who would help the Western Yugoslav comrades in their struggle against Pašić’s oppression on the one hand, and the BANU and Broad Socialists, who sought to combat hunger, diseases and economic collapse with a more moderate agenda that could, they hoped, be supported by the bourgeois Democratic Party and members of the old administrative apparatus, too, and laid their trust with regards to foreign policy in the hands of their UoE patrons to represent their interests in Paris, could no longer be denied. The national elections, scheduled after the country’s Christmas celebrations in the first half of January, were the natural moment in which coalition partners could revert to being competitors. The open question was whether the coalition would last until then.

The slim prospects of Blagoev’s project of a unified radically revolutionary socialist party for all countries of the Balkans, who would overcome the divisions of the nation states as a preliminary step towards achieving worldwide socialist brotherhood, could be clearly observed by anyone paying attention to what happened on the Northern bank of the Danube. Cristian Rakovsky’s mission among Romania’s Social Democrats was failing miserably. While he did win over a few staunch internationalists, their numbers were negligible even in the context of a comparatively underdeveloped labour movement such as the Romanian one. Romania’s Social Democratic Party, which had been banned and persecuted by King Ferdinand’s government for their anti-war stance, was immensely relieved to be able to operate freely now – a move which Ion I. C. Brătianu’s government undertook only after their UoE allies applied significant pressure – and it rode on the wave of nationalist euphoria which came with the Romanian army’s advance into Transilvania and later Banat and, throughout November, the increasingly clear signs that both regions as well as Southern parts of the Bucovina would be able to join the Old Kingdom to form a Greater Romania. Brătianu had pushed through electoral and agrarian reform. The former gave Social Democrats and Ţărănişti (the Peasant Party) better chances in the scheduled March 1919 elections, and while Brătianu’s National Liberals hoped that agrarian reform would take away the latter party’s main raison d’ être, the Social Democrats were able to mobilise their support base with demands for the eight hour workday and legal recognition of the role of unions in collective bargaining, which Brătianu was not yet willing to concede. [4] Overall, Social Democrats both in the Old Kingdom and in Transilvania joined all other Romanian parties in supporting Unification – in their view, this was not a propitious moment for airy-fairy dreams of a Red Super-Balkan Federation; they needed to appear as good Romanian patriots now, leaders like Constantin Titel Petrescu and Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor thought, and ride the wave on which their primary source of protection (the UoE) and the royal Romanian government they fought against presently surfed together.

All was not well between Romania and the Union of Equals, though. They had fought and won against most Central Powers, yes, and in late October, they were able to chase away the Szeklers’ Legion from Transilvania in the Battle of Turda and coerce Count Karoly’s Hungarian government to acknowledge Transilvania’s secession from Hungary and its unification with Romania. But not only did Brătianu and the PNL resent the political pressure they felt themselves under to implement an agenda of social and political reform. The harmony was also disturbed by the Bessarabian Question. Brătianu, and with him the great majority of the old political elites, felt elated by the impending inclusion of Transilvania and Banat into Greater Romania, but to them, Greater Romania was not complete without those parts of Moldova which had been conquered by the Russian Empire in the 19th century. In the disputed region, a parliamentary assembly (“Sfatul Ţării”) had passed a much more radical land reform, and was urging Moscow to be allowed to constitute itself as the (ethnically, linguistically and religiously heterogenous) Bessarabian Federative Republic within the Union of Equals. As long as Romanian assistance in defending the front lines against the Central Powers had been essential, Moscow had held back on these plans. Now, with the war won, Bessarabia’s social democratic leaders Ion Inculeţ and Ecaterina Arbore, who were under internal pressure from Romanian nationalists, insistently called for official recognition of their socio-economically more radically transformative, multi-cultural republic and a guarantee against its absorption into an ethnically much more homogeneous, politically more conservative Kingdom of Romania. Throughout November, intense negotiations were conducted, thinly veiled threats exchanged… and quite a viable solution was found. Bessarabia would constitute itself as a Federative Republic of the Union of Equals (and participate in the UoE general elections in December as such), but there would be free movement of goods and persons between Romania and Bessarabia (and, by implication, the entire Union of Equals). Formerly Austrian Bucovina would be partitioned, with its Northern half joining the Ukrainian Federative Republic of the UoE and its Southern half being incorporated into the Kingdom of Romania.

While this was a respectable deal by all means, Brătianu nevertheless resigned from his position immediately after its conclusion, choosing to lead the PNL into the next elections on a nationalist platform which emphasized Romania’s political independence from the UoE and kept “the full completion of Romania’s unification” as a goal still to be reached by the party.

What to Romania was a triumphant national liberation was a bitter national humiliation to Hungary. Count Karoly’s left-liberal government, and especially his Minister for National Minorities, Oskar Jászi (Civic Radical Party), had invested great hope and whatever was available in resources into helping Transilvania and the Banat transforming into autonomous “cantons” of what he envisioned as a future Hungarian-led “Switzerland of the East”. While the Banat Republic, proclaimed in Temesvar as early as late September, remained committed to this project and was only dissolved when Romanian troops progressed Northwards on the Eastern bank of the Danube and Serbian troops on the river’s left bank, forcing the Banat autonomist administration (prominently among them many people of German or Hungarian language and/or Jewish heritage) to flee further Northwards, the Council of Transilvania, convened at Alba Iulia, with its majority of Romanian-speaking delegates from Hungary’s Social Democratic Party and the National Romanian Party of Transilvania, opted for unconditional unification with the Kingdom of Romania early enough for its population to be able to vote in 1919’s Romanian parliamentary elections.

Having lost Slovakia and Banat to military defeat and Transilvania to both military defeat and semi-democratic vote [the Council of Transilvania was not really elected, just like most other emerging National Councils weren’t, IOTL as ITTL], Count Karoly, who had initially refused to enter negotiations for an armistice, arguing that his republic, much like that of the Czechoslovaks or the Southern Slavs, had emerged from under the oppression of the Habsburg rule and was not to be blamed for the monarchy’s war, ultimately realized that he had no chance but to accept the terms which the Entente presented to him: to withdraw behind basically the same lines that Hungary would end up with as national boundaries IOTL in the Treaty of Trianon. Having suffered this humiliating defeat, Karoly’s government began to buckle under increasing domestic pressure both from the Left and the Right. While both Left and Right oppositions were internally divided, too – on the right, those who rejected the abolition of monarchy and the restoration of a national republic disagreed with emphatically anti-Habsburg nationalist groups, while on the left, the Social Democrats suffered from much the same internal divisions like anywhere else –, they were each threatening to become too strong for Karoly’s unpopular coalition government. On the right, especially the Hungarian National Defense Association (MOVE), who united many former k.u.k. army officers in their ranks, threatened to undermine the army’s loyalty to Karoly’s government. On the left, the Social Democrats were radicalizing and bolstered by a wave of strikes and protests caused by the utter economic collapse which Hungary suffered as winter came and the country was cut off from its traditional coal supplies in (now Czechoslovak) Bohemia. People not only shivered in their unheated homes; goods, too, were unable to be shipped across the country as railroad transportation ceased to function for lack of fuel.

As November turned into December, Karoly’s government, which had called parliamentary elections for February 1919, was barely holding on to power, but various members of his government were already extending feelers to the right or the left, preparing to jump ship soon if the moment would come in which Karoly’s liberal government would ultimately fall.

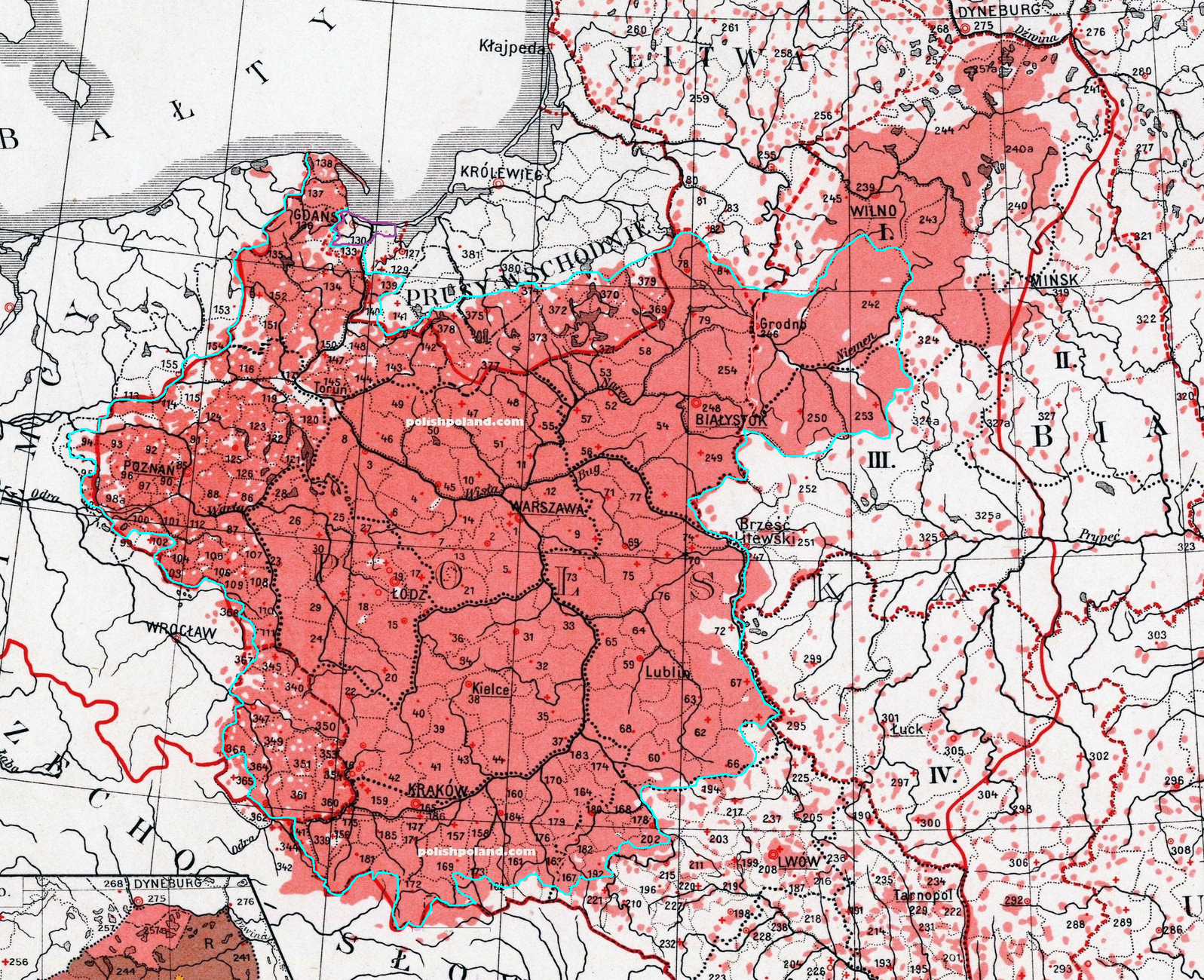

If Hungary’s borders were uncertain and its government threatened by a powerful opposition on both right and left, all of this applied to an even greater extent to Poland. At the moment of the conclusion of the Armistice of Absam, with the transition of power in Warsaw from Steczkowski to Pilsudski, commencing German withdrawal and cautious behavior initially displayed by the UoE’s military and political leaderships, it had appeared as if Poland was safely heading for independence, national unity and renewed strength. But even at that moment, this view would have ignored the great underlying (ideological as well as personal) political tensions in Polish politics as well as the complexity of the military situation in which Poland was caught. When Conservative Catholic groups in the Lithuanian Taryba called for Polish aid to wrest control over Vilnius from the radically leftist Commune, while the Naczelna Rada Ludowa in Poznan calls Dowbor-Musznicky’s Polish UoE Legions for help in its attempts to oust the German civil administration, too, from majority Polish-speaking regions in Prussia’s Posen province and beyond, those who were asked for help answered a call which revereberated deep within their respective formations, below ideological affiliations. Pilsudski, though nominally in the leadership of the Polish Socialist Party, crushed the Wilno Commune because he hoped that he could thus bring Poland and Lithuania back together again into a modern republic which could stand proudly on its own against the unenlightened and unpredictable Russian bear. The Polish UoE Legion helped the Nadek-dominated Poznan chapter of the POW to saw off a piece of Prussia-Germany because they saw the historical chance to revert a century-old aggressive wave of Germanic conquests which at times had come close to threaten to extinguish the Polish nation.

Both military formations not only found themselves in odd ideological company. They also soon discovered that their dual moves had brought them into a situation of irreconcilable rivalry – an awareness acutely helped by the frantic diplomatic negotiations undertaken among the Entente partners over how to respond to Friedrich Ebert’s German government’s bitter complaint over the POW’s forceful substitution of Prussian with Polish local administration. Britain’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Arthur Balfour, politely reminded everyone of the terms of the Armistice of Absam, in which a German military withdrawal behind the Oder was demanded, while German civil government in what had been the pre-war Empire would not be affected. Axelrod as well as France’s Foreign Minister Stéphen Pichon, on the other hand, pointed at Wilson’s Thirteenth Point, which demanded an emergent Polish state to comprise all clearly Polish-speaking regions and include an access to the Baltic Sea. Just as Axelrod backed Pichon’s views regarding Poland and Germany, who mirrored the primary French aim to defang Germany and make any further German attempt against France unlikely in the foreseeable future, Pichon also backed Axelrod’s insistence that Pilsudski’s forces had nothing whatsoever to do in Vilnius – a view which Lansing shared, too.

Seeing himself isolated over the Polish Question, Balfour soon backpedaled. This was the last moment in which Pilsudski might have remained the universally acknowledged Marshall of the military forces of the nascent Polish Republic, had he withdrawn all and any of his forces from Lithuania. But this was no longer possible for him – not only had he propped up a weak faction around Jouzas Gabrys [5] in Lithuania and angered all the others, from the Christian Democrats to the socialists, and even the conservative Party of National Progress distanced themselves, so Pilsudski’s withdrawal would certainly have brought anti-Polish forces to power in Vilnius quickly. More importantly, though, Pilsudski’s invasion had mobilized thousands of ethnic Poles in Vilnius and the rest of Southern Lithuania, who had organized into their own section of the POW over the past few weeks. Pilsudski allegedly even did try to order a retreat already in a meeting with his “generals” on November 13th, but, some sources say, those representing the Wilno section of the POW flatly refused and even threatened to block their passage – after the intervention, many ethnic Poles feared violent retributions against them [6]. This may or may not be true – either way, Pilsudski hesitated and stayed in Vilnius too long. By November 16th, all important Entente nations had jointly declared to recognize the ND-dominated Naczelna Rada Ludowa in Poznan, instead of the PPS-dominated Provisional Polish Government in Warsaw, as the official representation of the Polish nation, which would also be invited to join the Peace Conference in Paris.

When Pilsudski did retreat from Vilnius on November 21st, it was too late, and he found himself faced with a communiqué which dismissed him from the position of Marshall of the Polish Republic. In his absence, the PPS split over the question of whether to remain loyal to Pilsudski and his Eastern focus or play by the Entente’s rules and integrate with the NRL. Ignacy Daszinsky, once a close friend and ally of Pilsudski’s, convinced the socialists from the former Austrian partition to go with the latter route – a betrayal Pilsudski would not forget. Jedrzej Moraczewski secured the acquiescence of most workers’ councils with the switch to a coalition government between the (larger faction) of the PPS and the right-wing NDs. Pilsudski’s loyalists, led by Tytus Filipowicz, left the PPS to found the Polish Revolutionary Socialist Party. Pilsudski refused to stand down – and by the end of November, Poland, while having secured military as well as political control over significant portions of formerly Prussian-controlled territory, was on the brink of a civil war.

When Pilsudski left Vilnius and another round of violence erupted in the city, the Second and Third Union Armies were both not too far away to intervene – but they abstained from such action, on political orders. Supreme Commissioner Kamkov was determined to honor the promise of independence his predecessor Chernov had given (and also not to risk unpopular deaths in a poorly structured quagmire only weeks before the general elections). Thus, he would not to send forces into Lithuania unless they were called by a democratically elected Lithuanian body.

Also, the Second as well as the First Union Army, along with ample Republican Guards and Latvian and Estonian forces, had their hands full in the Northern Baltic, where one of the darkest tragedies of the postwar months began to unfold. The Baltic German minority, descendants of the colonists who had come under the protection of the crusading Livonian Order, had coexisted peacefully for several centuries now with their Baltic-, Uralic- and Slavic-speaking neighbors. They made up a large part of the landowning nobility, but in total far more German speakers lived in the towns than in country manors by 1918. In 1917’s February Revolution, ethnic Germans in Riga and Reval (Tallinn) as well as in the empire’s military service had, for the largest part, supported the new liberal order as well as the budding movements for the autonomy of the Baltic lands.

But the course of the revolution in 1917 had worsened these relations, as the Latvian and Estonian peasantry began to press for expropriations of the Baltic German nobility, and the proletariat of the polyglot towns espoused increasingly radical socialist views. Thus, when the German Army occupied Latvia and Estonia, and especially after the fall of Petrograd, when they installed their puppet Provisional All-Russian Government, Markov’s puppet regime found above-average support and loyalty among the Baltic Germans, especially among the landowning and (former) military elites. Baltic German cooperation was so much smoother than anybody else’s in Markov’s little dictatorship that he vehemently objected to the OHL’s plans for the establishment of a separate United Baltic Duchy – which did not keep Ludendorff and Hoffmann from preparing such plans.

This cooperation with Markov’s extremist right-wing tyranny which squeezed as many resources out of the Baltics and occupied Russia as possible to feed the German war machine had made the privileged minority extremely unpopular, and when the tide had turned, they paid a horrible price. Already throughout August and September, upon the collapse of Markov’s regime, local and poorly coordinated acts of “revenge” had resulted in violent plunderings of Baltic German estates, which left over a hundred people dead. When Latvian and Estonian forces, Republican Guards and two Union Armies marched in to restore the two federative republics and disarm von Hutier’s encircled Eighth German Army, the situation was calmed in many places, where military units upheld law and order and stepped in against spontaneous pogroms. In other places, though, the incoming military forces began to engage in coordinated campaigns, which took the inter-ethnic violence to an entirely new level. Especially Jukums Vācietis’ Latvian forces, but also a number of Republican Guards of mixed background, engaged in brutal acts which amounted to a campaign of ethnic cleansing. Von Hutier’s Army was not spared, either. When it became evident that significant numbers of German soldiers had escaped into the woods to avoid UoE captivity, the commander of the First Union Army ordered to forcibly march the prisoners all the way to the few major towns, where they were packed onto overcrowded freight trains and sent on a long journey Eastwards, on which hundreds would perish.

Some of those who had escaped into the woods, often with as much equipment as they could carry, joined groups of German civilians who sought to defend themselves against the persecutions, forming – a phenomenon which sprung up across much of the continent like mushrooms – a Baltic version of “Heimatwehren”. But the emergence of organized resistance only made matters worse for the German-speaking population of the Baltics: it gave Vācietis et al. a military reason to ratchet up the ethnic cleansing. When the first Baltic German Heimatwehren appeared in the towns, too, all urban German speakers came under fire, too.

The People’s Commission was extremely dissatisfied with the reports they received from the Baltic coast, to say the least. Kamkov and Axelrod planned to exploit the Union of Equal’s status of maltreated victims of the German Empire’s atrocious warfare and disastrous occupation and the sympathy bonus they hoped this brought them to the Union’s best advantage – but news of UoE military units committing their own wave of atrocities against the Baltic Germans threatened to annihilate this bonus. Pavel Lazimir, the Voykom, increased the internal pressure to stop the excesses and to adopt a more cautious approach in combatting any German resistance; yet at the same time, he also held his powerful protecting hand over any military personnel with blood on their hands, preventing the imprisonment and indictment of even one of those who were responsible for the atrocities against the Germans until decades after the deeds.

While the restoration of the Latvian and Estonian Federative Republics came at a bloody price, the establishment of a new federative republic to their South-East proceeded extremely smoothly. Already days after the conclusion of the Armistice of Absam and the beginning withdrawal of German occupation troops, a Belorussian Rada convened in Minsk. Dominated by moderate socialists of various ethnic backgrounds, the Rada immediately pursued the goal of establishing a Belorussian Federative Republic – a goal which was achieved on November 26th with the conclusion of the Concord between the Belorussian Rada and the Constituent Assembly in Moscow, just in time to define the procedure under which the UoE general elections would be held in Belarus and under which circumstances it could send how many delegates into the electoral college which chose the Union’s next president.

After the USPD’s Leipzig Congress, in which the Spartakusbund left the party and gave the signal for all its members and allies to immediately rise against the old monarchical order, the military leadership, and the capitalist system of exploitation, Ebert’s imperial government was in panic. It was impossible for the authorities to gauge just how many USPD members would turn out to be Spartakists, and indeed the violent takeover of power in the Free Hanseatic City of Hamburg and in the Silesian city of Breslau (where Rosa Luxemburg was liberated from prison) by Spartakus-dominated soldiers’ councils gave them reason to be very concerned. Ebert was loathe to grasp the extended hand of the moderate USPD leadership for negotiation, and his Minister for Defense, Gustav Noske, their coalition partners, the Kaiser and the military leadership were even more loathe to do so. But Ebert was a pragmatic, too. He knew that Polish rebels were about to wrestle control over Prussia’s Eastern provinces from the German civil authorities, he knew that thousands were dying of the flu every day and that more would starve if economic production could not be restored to normalcy. He saw that only the USPD could provide them with the necessary intelligence about impending revolts and the political capital to bring those parts of the proletariat who had been estranged from the SPD back onto legal terrain. Thus, phones were picked up…

On November 16th, when Hamburg was already restored to its old municipal government by the intervention of army units stationed at Altona, an alliance of Heimatwehren and returned regular troops had slaughtered enough Spartakists in Breslau to cause their control over the city to collapse, and other attempted Spartakist uprisings in Berlin and Stuttgart had been drowned in blood, too, Friedrich Ebert (as chancellor), Philipp Scheidemann (as chairman of the SPD and leader of its SPD Reichstag faction) and Hugo Haase (as chairman of the USPD and leader of its Reichstag faction) signed an agreement which sealed the extension of the coalition of SPD, FVP and Zentrum to include the USPD to form the “Front of National Salvation”. Under the terms of the agreement, all political prisoners who were not Spartakists or “anarchists” would be immediately released, a moratorium for political strikes for the rest of the year was agreed upon, and all involved parties committed themselves to endow the National Constituent Assembly as well as the constituent assemblies in all member states (except for Prussia) with the full freedom to decide the future forms of government democratically and unrestrained. (Although Gustav Stresemann had publicly repented in a Reichstag speech his enthusiastic support for expansionist policies in the early years of the war in order to facilitate his party’s entry into the Front of National Salvation coalition, too, a majority of his party’s Reichstag delegates rejected this idea when they realized that the above-mentioned agreement meant that the constituent assemblies could oust the Kaiser and any local monarchs, too.)

While the USPD’s entry into the coalition stabilized Germany internally, the situation on its borders caused a growing national panic. In the West, French, Belgian, British and US troops occupied the left bank of the Rhine and a number of bridgeheads on the right side of the Rhine, too, but kept German civil administration in place. In the East, though, the Polish Poznan RNL began to incorporate the towns and villages militarily controlled by the POW into its nascent administrative apparatus, making it perfectly clear that they expected all majority-Polish territories (under which they subsumed Kashubian-speaking groups, too) to be part of the Polish Republic henceforth. Combined with news of violence against Germans in Latvia and Estonia, this triggered a popular wave of enlistment in nationalist Heimatwehren, primarily but not exclusively in ethnically heterogeneous border regions. Noske’s ministry was increasingly counting on these inoffficial militia to circumvent the empire’s obligation to withdraw all military forces beyond the Oder, and worked with the military towards inofficial solutions in which military equipment, which had been agreed to be left behind for the Entente occupying forces to collect, would be handed over to local Heimatwehr units and hidden away. None of this must be allowed to become known – for officially, Ebert’s government was now playing the role of the persecuted innocence, lamenting anti-German excesses in the Baltics and at the hands of the Poles who violated the terms of the Armistice, while the Germans were faithfully implementing its provisions to the last letter.

This strategy was pompously subverted, though, when Kaiser Wilhelm II. held a speech before a large and angry crowd in Berlin on December 1st, though, in which he denounced Polish and “Russian” aggression and declared: “The German people has declared before all the world its unconditional desire for peace and laid down all arms to stop the great tragedy which has brought ruin over our continent. Now we are being raped by the victors. But we will not suffer all and any injustice and humiliation – there is a limit which must not be crossed. If we are pained beyond endurance, we cannot help it, we will lash out ultimately.” His speech, enthusiastically cheered by members of the nationalist Heimatwehren and met with furious boos and jeers by protesters with red banners, left Ebert’s government domestically and internationally embarrassed, and threatened to exert such centrifugal forces that the survival of the newly-forged coalition was immediately thrown into question as the USPD loudly demanded the Kaiser’s demission in the Reichstag once again, only to be decried by the restructuring far right as “traitors of the fatherland”.

Italy was one of the victorious nations of the Great War – yet this apparently did not calm the conflict-ridden country at all. If anything, tensions which had been suppressed during the immense effort of the war now seemed to come to the fore again.

First of all, there was the chaotic situation within the socialist movement. While undoubtedly a powerful force especially in the industrialised Northern half of the country, the socialists were undergoing a phase of great internal divisions, which had only been exacerbated by the PSI congress of September 1918.

A week after the attack on Turati, the police had apprehended a suspect for the attempted assassination: Cesare Rossi, an Independent Socialist and close associate of Benito Mussolini. Both rejected these accusations and the latter, in his first-page articles in the Quotidiano dei Combattenti Socialisti, publicly blamed Rome’s police prefecture of playing a political game at the behest of Orlando’s government by framing Rossi with the aim to discredit his movement.

Most socialists sided with the national coalition government on this question, not doubting a single second that indeed one of Mussolini’s men had been firing at Turati, and hurled furious accusations at the “Independent Socialists”, whose nationalism and militarism they abhorred anyway. One of the leading Maximalists, Giacinto Menotti Serrati, though, actually concurred, in an article for the PSI’s official newspaper Avanti!, with Mussolini’s accusation of manipulations. Only Serrati insinuated that the goal of the conspiracy had not been to discredit the Independent Socialists, but to shut down the PSI congress and prevent it from formulating a coherent transformational agenda for Italy.

Following Serrati’s front-page article, which almost coincided with the Armistice of Absam and thus came only weeks before the beginning of partial Italian demobilization (occupying Austria and parts of Yugoslavia and Albania took a lot of troops, but still considerably less than conducting offensive war operations), protest marches – the first of these in Milan – regularly turned into violent streetfights: Maximalist Socialists and anarchists against the police, internationalist Socialists against Independent Socialists, left-syndicalists against right-syndicalists, Independent Socialists against the police, too… In a number of provinces, curfews were ordered – some in the name of quarantine and the containment of the Spanish Flu pandemic, others openly aimed against the political violence. Once again, local police who had to enforce the curfew became the target of attacks – and sometimes their source, too, as in the case of the death of the 17-year-old syndicalist Daniele Fratelli [7] of Parma.

While the socialist opposition was divided, those moderate socialists who supported the “Unione Sacra” achieved important reforms: only weeks after the conclusion of the war, a reform of the Election Law replaced the old first-past-the-post system with proportional representation (with preferential voting within lists). The PSI Minister for Agriculture, Luigi Montemartini, spearheaded a “cereal offensive” in which hundreds of agricultural co-operatives across the country would be supported by the government in switching to new and improved varieties of wheat developed by Nazareno Strampelli, and the creation of new co-operatives was facilitated. The Ministers from the Reformist Socialist Party, who had split from the PSI in 1912 already, Ivanoe Bonomi (public works) and Leonida Bissolati continued with their largely successful work, too, the latter tasked with the increasingly dramatic challenge of providing aid to the wounded of the war and the returning veterans.

Italy had been awarded sizable occupation zones, mostly in the formerly Habsburg lands: much of Western Austria, parts of Slovenia, a large number of Dalmatian islands as well as half of Albania came under temporary Italian control. In Albania, which, US President Wilson insisted, should emerge as an undivided sovereign nation state, the Italian occupation zone bordered on those of the Serbian and the Greek military forces.

In Greece, the victorious ending of the Great War had strengthened the Venizelists, who were now preparing a national referendum on the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a Greek Republic. But more pressing was, for the moment, the challenge of taking care of more than a million refugees, who had fled the persecutions in the Ottoman Empire. Eleftherios Venizelos’ government had obtained the agreement of the other Entente powers to occupy the last European / Rumelian territory of the Ottomans except for Constantinople, which was jointly controlled by an Entente Council, as well as Smyrna and its environs in order to protect the Greek minority which still lived there. (Other Greek “islands” were under the control of other Entente members: the Pontic Greeks were “protected” in a zone occupied by the Union of Equals, while the Greeks in the South-East now lived in a region into which British and French forces were slowly filtering to estbablish a joint OETA zone. By late October, all projected Greek troops had arrived in Smyrna – but they did not calm the situation in the coastal city at all. Now, violent retributions against Smyrna’s Turks began to occur, and the Greek occupation not only turned a blind eye on them; Greek soldiers were also seen in many cases to have participated in plunderings. The Ottoman government in occupied Constantinople protested – but by late November, no action was taken to calm the situation in Smyrna. [This is basically OTL, except for the UoE occupation zone and, of course, the existence of a huge Armenian Federative Republic next to it.]

[1] If we’re turning a blind eye on the different voting ages for men and women…

[2] Well, only for men who had served in the army and not for women, but we’ll come to that. Still a massive expansion of the suffrage.

[3] Thought this is a complicated matter. More on that below.

[4] Unsurprisingly. The National Liberals were the major party of Romania’s old oligarchy and especially of its bourgeois wing, and while the Peasant Revolt of 1907 had demonstrated the need for a land reform even to the PNL, major concessions to the urban labour movement were not yet felt to be necessary (the strikes of 1920 or 1929 have not yet happened).

[5] He was among the few Lithuanian politicians actually involved in Pilsudski’s OTL coup which attempted to install a pro-Polish government in Kaunas.

[6] Given the amount of inter-ethnic violence occurring IOTL, this may not have been an unfounded anxiety.

[7] Don’t look him up, he’s just a youngster I made up.

Most prominently in Europe, but also in other parts of the world, the intense relief felt by the population after the Great War had finally ended on October 19th was slowly giving way to an atmosphere of confusion.

Late October and November 1918 was when the deadly second wave of the Spanish Flu washed over the continents, killing millions of people. It was also the time of other, much more ambiguous, and sometimes outright enthusiastic waves: universal suffrage was being legislated or applied for the first time in the United Kingdom [1], in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Italy [2], Poland [3], Romania (and Uruguay, even though remote from the events of the Great War). A first wave of soldiers returned home, scarred by their experiences in the Great War. Worker and peasant unrest rocked Germany and Yugoslavia – a phenomenon which would spread to other peoples in the months to come, as more and more demobilized soldiers returned into an economy hit by destructions, horrendous public debts, and in full conversion from war to peace production. Surging nationalism created tensions involving Germans and Poles, Poles and Lithuanians, Croats and Serbs, Hungarians, Slovaks, Serbs, and Romanians, Greeks and Turks, Estonians, Latvians and Baltic Germans, and many others.

Early in the month, in elections to the House of Representatives and the Senate, US President Woodrow Wilson’s Democratic Party narrowly lost control over both houses of Congress [like OTL]. Nevertheless, Wilson’s administration remained intensely engaged in preparing the ground for peace negotations, which were planned to begin in December in Paris, as well as in attempting to prevent the Europeans from jumping at each others’ throats again.

The latter was a gig+antic task indeed.

The newly established State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, who sought unification with the Kingdom of Serbia, for example, was confronted with massive popular resistance against unification under the Djordjevic dynasty in parts of Croatia and Bosnia, where the rebels included armed and experienced men from the Green Cadres. The nascent SHS state was still weak, but to its luck, its opponents were plagued with internal divisions, too: a “Democratic Yugoslav Committee” under Stjepan Radić fought for a democratic and federal Yugoslavian republic, which would include at least Bulgaria, too, and possibly even Albania, while other rebel groups preferred an independent Croatia, with some of the latteri favouring a monarchy and others a republic. The rebellious peasantry sympathized with revolutionary Narodnik ideas about land repartition, while groups affiliated with the Catholic Church were much more conservative in nature and abhorred the idea of the “Russian virus” spreading to Southern Slavic lands. As a consequence, the forces loyal to the SHS National Council, aided by Serbian detachments and tacitly by the British and French units present in the region, too, began to gain the upper hand in the chaotic situation of violent streetfighting which haunted the larger towns of Croatia by the end of October. The anti-Pašić rebel coalition received far less foreign support – both the Union of Equals and the new Bulgarian Republic viewed the agrarian revolutionaries and socialists among them with great sympathy, but the geographical presence of Serbia between them and Slovenia-Croatia-Bosnia prevented them from providing any significant amount of concrete support which went beyond diplomatic protests against the “bloody oppression of democratic expressions of national self-determination”. The Italian government, on the other hand, began to quietly ship support to radical Catholic groups in Croatia in late October, but this was barely enough to prevent their total annihilation. Thus, the rebels were not defeated – they still controlled great parts of the countryside –, but they were driven into the mountains, from where they would continue their fight, from mid-November finally at least formally united in a counter-“Mostar government”. On the diplomatic stage, the Mostar government’s stance was not too promising, either: While the Union of Equals’ Foreign Commissioner Axelrod emphatically spoke out for the right of all South Slavs to determine the shape of their future state in a grassroots, bottom-up process of nation building, Britain and France insisted on the framework agreed upon in the Corfu Declaration, and while the US position was less determined yet and more of a vaguely pro-Yugoslavia stance, Secretary of State Robert Lansing had already made it clear that it would be unacceptable to the US if the defeated Central Power Bulgaria had a say in the process of its formation. Throughout November, Axelrod was forced to increasingly moderate his criticism, though, in order not to risk the loss of credibility of the UoE’s foreign policy with the pursuit of contradictory policies in the Yugoslav and the Polish Questions [see more below, or rather: tomorrow, when I’ll have finished the part on Poland].

Under these circumstances, the SHS National Council in Zagreb announced on November 28th that elections for a constituent assembly for a unified Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, which would encompass the formerly Habsburg SHS territories as well as Serbia and, if things went well, Montenegro, would be held in late January. Two days later, the Mostar counter-government announced to hold rivalling elections to “Federative Republics of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina” (envisioned to become part of a greater Yugoslav federation one day) a week earlier.

These events represented the first foreign policy failure of the young Bulgarian Republic. Its governing coalition of the agrarian BANU and various Social Democratic parties, headed by the People’s Supreme Commissioner Alexander Stambolinsky, was more successful with its domestic reforms, though. Village committees were reformed to oversee and implement the agrarian reform which the revolutionary Commission had decreed, and workers’ councils were forming everywhere and endowed by the government with far-reaching powers to manage the conversion of the country’s wartime economy to peace production – a gigantic challenge which met, at every step, with protests and attempted obstructions. The dire state of food production and distribution as well as the overstrain of the country’s medical services faced with yet another pandemic wave further contributed to a general state of turmoil. The continued presence of UoE Republican Guards in the country helped calm the situation, though, and allowed Stambolisnky’s government, whose security forces were in a process of disintegration, to steer through the troubled revolutionary waters without being overthrown, slowly building up alternative security structures based on the agrarian and proletarian parties’ Orange and Red Guards. As the government reasserted its control over key public services and the danger of counter-revolution appeared to wane by the end of November, it became increasingly clear that the revolutionary coalition of the BANU, the Wider Socialists and the Narrower Socialists would not stay together for much longer. The divergences between Dimitar Blagoev’s Narrow Socialists, who hoped to unify all radical revolutionary socialist parties of the wider Balkan region, clamoured for widespread confiscations and immediate nationalization of all industries as well as for the formation of voluntary proletarian corps who would help the Western Yugoslav comrades in their struggle against Pašić’s oppression on the one hand, and the BANU and Broad Socialists, who sought to combat hunger, diseases and economic collapse with a more moderate agenda that could, they hoped, be supported by the bourgeois Democratic Party and members of the old administrative apparatus, too, and laid their trust with regards to foreign policy in the hands of their UoE patrons to represent their interests in Paris, could no longer be denied. The national elections, scheduled after the country’s Christmas celebrations in the first half of January, were the natural moment in which coalition partners could revert to being competitors. The open question was whether the coalition would last until then.

The slim prospects of Blagoev’s project of a unified radically revolutionary socialist party for all countries of the Balkans, who would overcome the divisions of the nation states as a preliminary step towards achieving worldwide socialist brotherhood, could be clearly observed by anyone paying attention to what happened on the Northern bank of the Danube. Cristian Rakovsky’s mission among Romania’s Social Democrats was failing miserably. While he did win over a few staunch internationalists, their numbers were negligible even in the context of a comparatively underdeveloped labour movement such as the Romanian one. Romania’s Social Democratic Party, which had been banned and persecuted by King Ferdinand’s government for their anti-war stance, was immensely relieved to be able to operate freely now – a move which Ion I. C. Brătianu’s government undertook only after their UoE allies applied significant pressure – and it rode on the wave of nationalist euphoria which came with the Romanian army’s advance into Transilvania and later Banat and, throughout November, the increasingly clear signs that both regions as well as Southern parts of the Bucovina would be able to join the Old Kingdom to form a Greater Romania. Brătianu had pushed through electoral and agrarian reform. The former gave Social Democrats and Ţărănişti (the Peasant Party) better chances in the scheduled March 1919 elections, and while Brătianu’s National Liberals hoped that agrarian reform would take away the latter party’s main raison d’ être, the Social Democrats were able to mobilise their support base with demands for the eight hour workday and legal recognition of the role of unions in collective bargaining, which Brătianu was not yet willing to concede. [4] Overall, Social Democrats both in the Old Kingdom and in Transilvania joined all other Romanian parties in supporting Unification – in their view, this was not a propitious moment for airy-fairy dreams of a Red Super-Balkan Federation; they needed to appear as good Romanian patriots now, leaders like Constantin Titel Petrescu and Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor thought, and ride the wave on which their primary source of protection (the UoE) and the royal Romanian government they fought against presently surfed together.

All was not well between Romania and the Union of Equals, though. They had fought and won against most Central Powers, yes, and in late October, they were able to chase away the Szeklers’ Legion from Transilvania in the Battle of Turda and coerce Count Karoly’s Hungarian government to acknowledge Transilvania’s secession from Hungary and its unification with Romania. But not only did Brătianu and the PNL resent the political pressure they felt themselves under to implement an agenda of social and political reform. The harmony was also disturbed by the Bessarabian Question. Brătianu, and with him the great majority of the old political elites, felt elated by the impending inclusion of Transilvania and Banat into Greater Romania, but to them, Greater Romania was not complete without those parts of Moldova which had been conquered by the Russian Empire in the 19th century. In the disputed region, a parliamentary assembly (“Sfatul Ţării”) had passed a much more radical land reform, and was urging Moscow to be allowed to constitute itself as the (ethnically, linguistically and religiously heterogenous) Bessarabian Federative Republic within the Union of Equals. As long as Romanian assistance in defending the front lines against the Central Powers had been essential, Moscow had held back on these plans. Now, with the war won, Bessarabia’s social democratic leaders Ion Inculeţ and Ecaterina Arbore, who were under internal pressure from Romanian nationalists, insistently called for official recognition of their socio-economically more radically transformative, multi-cultural republic and a guarantee against its absorption into an ethnically much more homogeneous, politically more conservative Kingdom of Romania. Throughout November, intense negotiations were conducted, thinly veiled threats exchanged… and quite a viable solution was found. Bessarabia would constitute itself as a Federative Republic of the Union of Equals (and participate in the UoE general elections in December as such), but there would be free movement of goods and persons between Romania and Bessarabia (and, by implication, the entire Union of Equals). Formerly Austrian Bucovina would be partitioned, with its Northern half joining the Ukrainian Federative Republic of the UoE and its Southern half being incorporated into the Kingdom of Romania.

While this was a respectable deal by all means, Brătianu nevertheless resigned from his position immediately after its conclusion, choosing to lead the PNL into the next elections on a nationalist platform which emphasized Romania’s political independence from the UoE and kept “the full completion of Romania’s unification” as a goal still to be reached by the party.

What to Romania was a triumphant national liberation was a bitter national humiliation to Hungary. Count Karoly’s left-liberal government, and especially his Minister for National Minorities, Oskar Jászi (Civic Radical Party), had invested great hope and whatever was available in resources into helping Transilvania and the Banat transforming into autonomous “cantons” of what he envisioned as a future Hungarian-led “Switzerland of the East”. While the Banat Republic, proclaimed in Temesvar as early as late September, remained committed to this project and was only dissolved when Romanian troops progressed Northwards on the Eastern bank of the Danube and Serbian troops on the river’s left bank, forcing the Banat autonomist administration (prominently among them many people of German or Hungarian language and/or Jewish heritage) to flee further Northwards, the Council of Transilvania, convened at Alba Iulia, with its majority of Romanian-speaking delegates from Hungary’s Social Democratic Party and the National Romanian Party of Transilvania, opted for unconditional unification with the Kingdom of Romania early enough for its population to be able to vote in 1919’s Romanian parliamentary elections.

Having lost Slovakia and Banat to military defeat and Transilvania to both military defeat and semi-democratic vote [the Council of Transilvania was not really elected, just like most other emerging National Councils weren’t, IOTL as ITTL], Count Karoly, who had initially refused to enter negotiations for an armistice, arguing that his republic, much like that of the Czechoslovaks or the Southern Slavs, had emerged from under the oppression of the Habsburg rule and was not to be blamed for the monarchy’s war, ultimately realized that he had no chance but to accept the terms which the Entente presented to him: to withdraw behind basically the same lines that Hungary would end up with as national boundaries IOTL in the Treaty of Trianon. Having suffered this humiliating defeat, Karoly’s government began to buckle under increasing domestic pressure both from the Left and the Right. While both Left and Right oppositions were internally divided, too – on the right, those who rejected the abolition of monarchy and the restoration of a national republic disagreed with emphatically anti-Habsburg nationalist groups, while on the left, the Social Democrats suffered from much the same internal divisions like anywhere else –, they were each threatening to become too strong for Karoly’s unpopular coalition government. On the right, especially the Hungarian National Defense Association (MOVE), who united many former k.u.k. army officers in their ranks, threatened to undermine the army’s loyalty to Karoly’s government. On the left, the Social Democrats were radicalizing and bolstered by a wave of strikes and protests caused by the utter economic collapse which Hungary suffered as winter came and the country was cut off from its traditional coal supplies in (now Czechoslovak) Bohemia. People not only shivered in their unheated homes; goods, too, were unable to be shipped across the country as railroad transportation ceased to function for lack of fuel.

As November turned into December, Karoly’s government, which had called parliamentary elections for February 1919, was barely holding on to power, but various members of his government were already extending feelers to the right or the left, preparing to jump ship soon if the moment would come in which Karoly’s liberal government would ultimately fall.

If Hungary’s borders were uncertain and its government threatened by a powerful opposition on both right and left, all of this applied to an even greater extent to Poland. At the moment of the conclusion of the Armistice of Absam, with the transition of power in Warsaw from Steczkowski to Pilsudski, commencing German withdrawal and cautious behavior initially displayed by the UoE’s military and political leaderships, it had appeared as if Poland was safely heading for independence, national unity and renewed strength. But even at that moment, this view would have ignored the great underlying (ideological as well as personal) political tensions in Polish politics as well as the complexity of the military situation in which Poland was caught. When Conservative Catholic groups in the Lithuanian Taryba called for Polish aid to wrest control over Vilnius from the radically leftist Commune, while the Naczelna Rada Ludowa in Poznan calls Dowbor-Musznicky’s Polish UoE Legions for help in its attempts to oust the German civil administration, too, from majority Polish-speaking regions in Prussia’s Posen province and beyond, those who were asked for help answered a call which revereberated deep within their respective formations, below ideological affiliations. Pilsudski, though nominally in the leadership of the Polish Socialist Party, crushed the Wilno Commune because he hoped that he could thus bring Poland and Lithuania back together again into a modern republic which could stand proudly on its own against the unenlightened and unpredictable Russian bear. The Polish UoE Legion helped the Nadek-dominated Poznan chapter of the POW to saw off a piece of Prussia-Germany because they saw the historical chance to revert a century-old aggressive wave of Germanic conquests which at times had come close to threaten to extinguish the Polish nation.

Both military formations not only found themselves in odd ideological company. They also soon discovered that their dual moves had brought them into a situation of irreconcilable rivalry – an awareness acutely helped by the frantic diplomatic negotiations undertaken among the Entente partners over how to respond to Friedrich Ebert’s German government’s bitter complaint over the POW’s forceful substitution of Prussian with Polish local administration. Britain’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Arthur Balfour, politely reminded everyone of the terms of the Armistice of Absam, in which a German military withdrawal behind the Oder was demanded, while German civil government in what had been the pre-war Empire would not be affected. Axelrod as well as France’s Foreign Minister Stéphen Pichon, on the other hand, pointed at Wilson’s Thirteenth Point, which demanded an emergent Polish state to comprise all clearly Polish-speaking regions and include an access to the Baltic Sea. Just as Axelrod backed Pichon’s views regarding Poland and Germany, who mirrored the primary French aim to defang Germany and make any further German attempt against France unlikely in the foreseeable future, Pichon also backed Axelrod’s insistence that Pilsudski’s forces had nothing whatsoever to do in Vilnius – a view which Lansing shared, too.

Seeing himself isolated over the Polish Question, Balfour soon backpedaled. This was the last moment in which Pilsudski might have remained the universally acknowledged Marshall of the military forces of the nascent Polish Republic, had he withdrawn all and any of his forces from Lithuania. But this was no longer possible for him – not only had he propped up a weak faction around Jouzas Gabrys [5] in Lithuania and angered all the others, from the Christian Democrats to the socialists, and even the conservative Party of National Progress distanced themselves, so Pilsudski’s withdrawal would certainly have brought anti-Polish forces to power in Vilnius quickly. More importantly, though, Pilsudski’s invasion had mobilized thousands of ethnic Poles in Vilnius and the rest of Southern Lithuania, who had organized into their own section of the POW over the past few weeks. Pilsudski allegedly even did try to order a retreat already in a meeting with his “generals” on November 13th, but, some sources say, those representing the Wilno section of the POW flatly refused and even threatened to block their passage – after the intervention, many ethnic Poles feared violent retributions against them [6]. This may or may not be true – either way, Pilsudski hesitated and stayed in Vilnius too long. By November 16th, all important Entente nations had jointly declared to recognize the ND-dominated Naczelna Rada Ludowa in Poznan, instead of the PPS-dominated Provisional Polish Government in Warsaw, as the official representation of the Polish nation, which would also be invited to join the Peace Conference in Paris.

When Pilsudski did retreat from Vilnius on November 21st, it was too late, and he found himself faced with a communiqué which dismissed him from the position of Marshall of the Polish Republic. In his absence, the PPS split over the question of whether to remain loyal to Pilsudski and his Eastern focus or play by the Entente’s rules and integrate with the NRL. Ignacy Daszinsky, once a close friend and ally of Pilsudski’s, convinced the socialists from the former Austrian partition to go with the latter route – a betrayal Pilsudski would not forget. Jedrzej Moraczewski secured the acquiescence of most workers’ councils with the switch to a coalition government between the (larger faction) of the PPS and the right-wing NDs. Pilsudski’s loyalists, led by Tytus Filipowicz, left the PPS to found the Polish Revolutionary Socialist Party. Pilsudski refused to stand down – and by the end of November, Poland, while having secured military as well as political control over significant portions of formerly Prussian-controlled territory, was on the brink of a civil war.

When Pilsudski left Vilnius and another round of violence erupted in the city, the Second and Third Union Armies were both not too far away to intervene – but they abstained from such action, on political orders. Supreme Commissioner Kamkov was determined to honor the promise of independence his predecessor Chernov had given (and also not to risk unpopular deaths in a poorly structured quagmire only weeks before the general elections). Thus, he would not to send forces into Lithuania unless they were called by a democratically elected Lithuanian body.

Also, the Second as well as the First Union Army, along with ample Republican Guards and Latvian and Estonian forces, had their hands full in the Northern Baltic, where one of the darkest tragedies of the postwar months began to unfold. The Baltic German minority, descendants of the colonists who had come under the protection of the crusading Livonian Order, had coexisted peacefully for several centuries now with their Baltic-, Uralic- and Slavic-speaking neighbors. They made up a large part of the landowning nobility, but in total far more German speakers lived in the towns than in country manors by 1918. In 1917’s February Revolution, ethnic Germans in Riga and Reval (Tallinn) as well as in the empire’s military service had, for the largest part, supported the new liberal order as well as the budding movements for the autonomy of the Baltic lands.

But the course of the revolution in 1917 had worsened these relations, as the Latvian and Estonian peasantry began to press for expropriations of the Baltic German nobility, and the proletariat of the polyglot towns espoused increasingly radical socialist views. Thus, when the German Army occupied Latvia and Estonia, and especially after the fall of Petrograd, when they installed their puppet Provisional All-Russian Government, Markov’s puppet regime found above-average support and loyalty among the Baltic Germans, especially among the landowning and (former) military elites. Baltic German cooperation was so much smoother than anybody else’s in Markov’s little dictatorship that he vehemently objected to the OHL’s plans for the establishment of a separate United Baltic Duchy – which did not keep Ludendorff and Hoffmann from preparing such plans.

This cooperation with Markov’s extremist right-wing tyranny which squeezed as many resources out of the Baltics and occupied Russia as possible to feed the German war machine had made the privileged minority extremely unpopular, and when the tide had turned, they paid a horrible price. Already throughout August and September, upon the collapse of Markov’s regime, local and poorly coordinated acts of “revenge” had resulted in violent plunderings of Baltic German estates, which left over a hundred people dead. When Latvian and Estonian forces, Republican Guards and two Union Armies marched in to restore the two federative republics and disarm von Hutier’s encircled Eighth German Army, the situation was calmed in many places, where military units upheld law and order and stepped in against spontaneous pogroms. In other places, though, the incoming military forces began to engage in coordinated campaigns, which took the inter-ethnic violence to an entirely new level. Especially Jukums Vācietis’ Latvian forces, but also a number of Republican Guards of mixed background, engaged in brutal acts which amounted to a campaign of ethnic cleansing. Von Hutier’s Army was not spared, either. When it became evident that significant numbers of German soldiers had escaped into the woods to avoid UoE captivity, the commander of the First Union Army ordered to forcibly march the prisoners all the way to the few major towns, where they were packed onto overcrowded freight trains and sent on a long journey Eastwards, on which hundreds would perish.

Some of those who had escaped into the woods, often with as much equipment as they could carry, joined groups of German civilians who sought to defend themselves against the persecutions, forming – a phenomenon which sprung up across much of the continent like mushrooms – a Baltic version of “Heimatwehren”. But the emergence of organized resistance only made matters worse for the German-speaking population of the Baltics: it gave Vācietis et al. a military reason to ratchet up the ethnic cleansing. When the first Baltic German Heimatwehren appeared in the towns, too, all urban German speakers came under fire, too.

The People’s Commission was extremely dissatisfied with the reports they received from the Baltic coast, to say the least. Kamkov and Axelrod planned to exploit the Union of Equal’s status of maltreated victims of the German Empire’s atrocious warfare and disastrous occupation and the sympathy bonus they hoped this brought them to the Union’s best advantage – but news of UoE military units committing their own wave of atrocities against the Baltic Germans threatened to annihilate this bonus. Pavel Lazimir, the Voykom, increased the internal pressure to stop the excesses and to adopt a more cautious approach in combatting any German resistance; yet at the same time, he also held his powerful protecting hand over any military personnel with blood on their hands, preventing the imprisonment and indictment of even one of those who were responsible for the atrocities against the Germans until decades after the deeds.

While the restoration of the Latvian and Estonian Federative Republics came at a bloody price, the establishment of a new federative republic to their South-East proceeded extremely smoothly. Already days after the conclusion of the Armistice of Absam and the beginning withdrawal of German occupation troops, a Belorussian Rada convened in Minsk. Dominated by moderate socialists of various ethnic backgrounds, the Rada immediately pursued the goal of establishing a Belorussian Federative Republic – a goal which was achieved on November 26th with the conclusion of the Concord between the Belorussian Rada and the Constituent Assembly in Moscow, just in time to define the procedure under which the UoE general elections would be held in Belarus and under which circumstances it could send how many delegates into the electoral college which chose the Union’s next president.

After the USPD’s Leipzig Congress, in which the Spartakusbund left the party and gave the signal for all its members and allies to immediately rise against the old monarchical order, the military leadership, and the capitalist system of exploitation, Ebert’s imperial government was in panic. It was impossible for the authorities to gauge just how many USPD members would turn out to be Spartakists, and indeed the violent takeover of power in the Free Hanseatic City of Hamburg and in the Silesian city of Breslau (where Rosa Luxemburg was liberated from prison) by Spartakus-dominated soldiers’ councils gave them reason to be very concerned. Ebert was loathe to grasp the extended hand of the moderate USPD leadership for negotiation, and his Minister for Defense, Gustav Noske, their coalition partners, the Kaiser and the military leadership were even more loathe to do so. But Ebert was a pragmatic, too. He knew that Polish rebels were about to wrestle control over Prussia’s Eastern provinces from the German civil authorities, he knew that thousands were dying of the flu every day and that more would starve if economic production could not be restored to normalcy. He saw that only the USPD could provide them with the necessary intelligence about impending revolts and the political capital to bring those parts of the proletariat who had been estranged from the SPD back onto legal terrain. Thus, phones were picked up…

On November 16th, when Hamburg was already restored to its old municipal government by the intervention of army units stationed at Altona, an alliance of Heimatwehren and returned regular troops had slaughtered enough Spartakists in Breslau to cause their control over the city to collapse, and other attempted Spartakist uprisings in Berlin and Stuttgart had been drowned in blood, too, Friedrich Ebert (as chancellor), Philipp Scheidemann (as chairman of the SPD and leader of its SPD Reichstag faction) and Hugo Haase (as chairman of the USPD and leader of its Reichstag faction) signed an agreement which sealed the extension of the coalition of SPD, FVP and Zentrum to include the USPD to form the “Front of National Salvation”. Under the terms of the agreement, all political prisoners who were not Spartakists or “anarchists” would be immediately released, a moratorium for political strikes for the rest of the year was agreed upon, and all involved parties committed themselves to endow the National Constituent Assembly as well as the constituent assemblies in all member states (except for Prussia) with the full freedom to decide the future forms of government democratically and unrestrained. (Although Gustav Stresemann had publicly repented in a Reichstag speech his enthusiastic support for expansionist policies in the early years of the war in order to facilitate his party’s entry into the Front of National Salvation coalition, too, a majority of his party’s Reichstag delegates rejected this idea when they realized that the above-mentioned agreement meant that the constituent assemblies could oust the Kaiser and any local monarchs, too.)

While the USPD’s entry into the coalition stabilized Germany internally, the situation on its borders caused a growing national panic. In the West, French, Belgian, British and US troops occupied the left bank of the Rhine and a number of bridgeheads on the right side of the Rhine, too, but kept German civil administration in place. In the East, though, the Polish Poznan RNL began to incorporate the towns and villages militarily controlled by the POW into its nascent administrative apparatus, making it perfectly clear that they expected all majority-Polish territories (under which they subsumed Kashubian-speaking groups, too) to be part of the Polish Republic henceforth. Combined with news of violence against Germans in Latvia and Estonia, this triggered a popular wave of enlistment in nationalist Heimatwehren, primarily but not exclusively in ethnically heterogeneous border regions. Noske’s ministry was increasingly counting on these inoffficial militia to circumvent the empire’s obligation to withdraw all military forces beyond the Oder, and worked with the military towards inofficial solutions in which military equipment, which had been agreed to be left behind for the Entente occupying forces to collect, would be handed over to local Heimatwehr units and hidden away. None of this must be allowed to become known – for officially, Ebert’s government was now playing the role of the persecuted innocence, lamenting anti-German excesses in the Baltics and at the hands of the Poles who violated the terms of the Armistice, while the Germans were faithfully implementing its provisions to the last letter.

This strategy was pompously subverted, though, when Kaiser Wilhelm II. held a speech before a large and angry crowd in Berlin on December 1st, though, in which he denounced Polish and “Russian” aggression and declared: “The German people has declared before all the world its unconditional desire for peace and laid down all arms to stop the great tragedy which has brought ruin over our continent. Now we are being raped by the victors. But we will not suffer all and any injustice and humiliation – there is a limit which must not be crossed. If we are pained beyond endurance, we cannot help it, we will lash out ultimately.” His speech, enthusiastically cheered by members of the nationalist Heimatwehren and met with furious boos and jeers by protesters with red banners, left Ebert’s government domestically and internationally embarrassed, and threatened to exert such centrifugal forces that the survival of the newly-forged coalition was immediately thrown into question as the USPD loudly demanded the Kaiser’s demission in the Reichstag once again, only to be decried by the restructuring far right as “traitors of the fatherland”.

Italy was one of the victorious nations of the Great War – yet this apparently did not calm the conflict-ridden country at all. If anything, tensions which had been suppressed during the immense effort of the war now seemed to come to the fore again.

First of all, there was the chaotic situation within the socialist movement. While undoubtedly a powerful force especially in the industrialised Northern half of the country, the socialists were undergoing a phase of great internal divisions, which had only been exacerbated by the PSI congress of September 1918.

A week after the attack on Turati, the police had apprehended a suspect for the attempted assassination: Cesare Rossi, an Independent Socialist and close associate of Benito Mussolini. Both rejected these accusations and the latter, in his first-page articles in the Quotidiano dei Combattenti Socialisti, publicly blamed Rome’s police prefecture of playing a political game at the behest of Orlando’s government by framing Rossi with the aim to discredit his movement.

Most socialists sided with the national coalition government on this question, not doubting a single second that indeed one of Mussolini’s men had been firing at Turati, and hurled furious accusations at the “Independent Socialists”, whose nationalism and militarism they abhorred anyway. One of the leading Maximalists, Giacinto Menotti Serrati, though, actually concurred, in an article for the PSI’s official newspaper Avanti!, with Mussolini’s accusation of manipulations. Only Serrati insinuated that the goal of the conspiracy had not been to discredit the Independent Socialists, but to shut down the PSI congress and prevent it from formulating a coherent transformational agenda for Italy.

Following Serrati’s front-page article, which almost coincided with the Armistice of Absam and thus came only weeks before the beginning of partial Italian demobilization (occupying Austria and parts of Yugoslavia and Albania took a lot of troops, but still considerably less than conducting offensive war operations), protest marches – the first of these in Milan – regularly turned into violent streetfights: Maximalist Socialists and anarchists against the police, internationalist Socialists against Independent Socialists, left-syndicalists against right-syndicalists, Independent Socialists against the police, too… In a number of provinces, curfews were ordered – some in the name of quarantine and the containment of the Spanish Flu pandemic, others openly aimed against the political violence. Once again, local police who had to enforce the curfew became the target of attacks – and sometimes their source, too, as in the case of the death of the 17-year-old syndicalist Daniele Fratelli [7] of Parma.