Chapter 13 - 1526 part 2 and 1527

Francis’s glory was tarnished by the death of Queen Claude weeks after Mohács. The delivery of her latest daughter in the autumn had been extremely difficult, and while baby Anne was thriving, her mother was the very opposite. Claude had suffered fainting spells, migraines and agues since the birth to such degree that the court physicians recommended to the king that he abstain from her bed for a long while. Her daughters had been placed in the care of their aunt as their mother was incapacitated and while Francis had never been in love or faithful to his wife, he seemed very concerned about her, even snapping at his mother to give her peace and quiet. Claude passed away from due to a fever spell in the company of her eldest son and husband late in the evening at Chambord, much to the dauphin’s grief. The king took François into his own chamber for the night where he consoled him until the boy had cried himself to sleep.

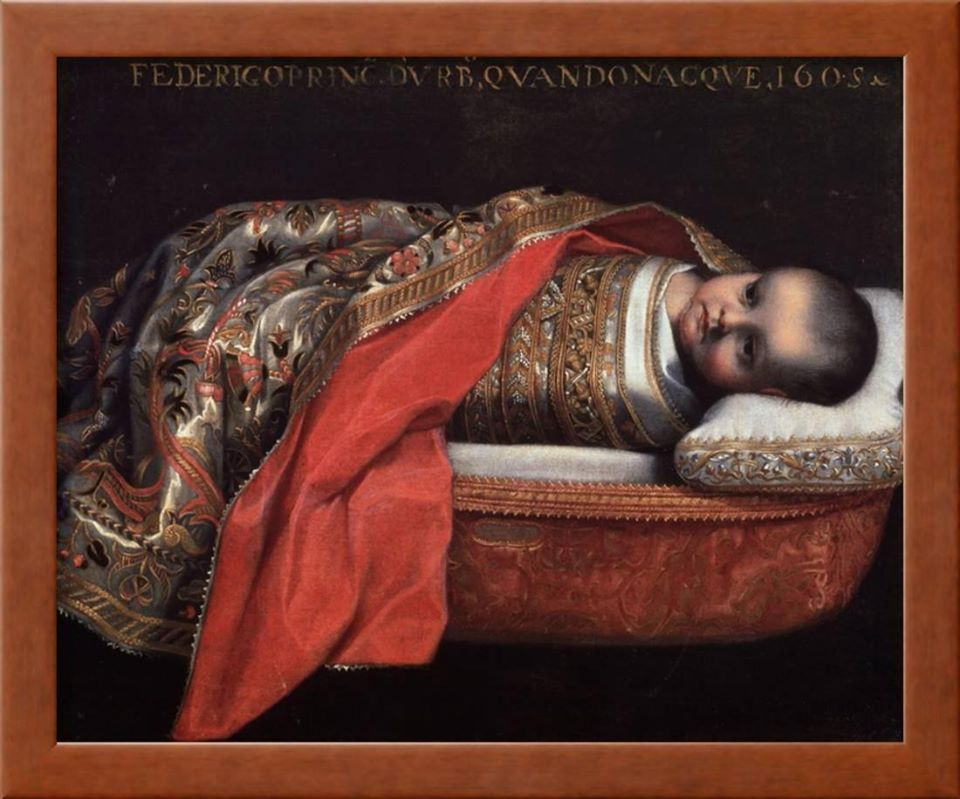

Claude of France, Queen Consort of France

Claude’s legacy to France had been rather meager in most regards except two: she had replenished the royal family several times over and given Brittany to the Valois dynasty. Louis XI had left one son behind and Charles VIII had died without heirs, while Louis XII had left two daughters behind. Claude had given Francis three healthy sons in addition to her daughters, securing the Valois-Angouleme dynasty. Her maternal inheritance of the duchy of Brittany was also firmly tied to the crown at her death, as the dauphin succeeded her as the Duke.

Francis would not be the only king becoming a widower in the spring; so did Joao III of Portugal as Catherine of Austria died. Her tenure as consort lasted around a thousand days and she left a frail newborn son behind, as her firstborn infanta Maria Isabel did not outlive her mother for long. Infante Alfonso died days later after his sister, leaving the king without heirs of his own. The sudden shock of Catherine’s death hit both Iberian kingdoms hard, Joao had been very fond of his wife and Ferdinand loved his youngest sister dearly. Both courts plunged into mourning, as the church bells rang in both kingdoms in sorrow. While Joao was still young and had brothers to spare, his second marriage would have to be taken into consideration and so would that of his siblings. Maria of Aragon had given the late king Manuel eight living children and now Joao decided to ensure that the future of Portugal would be secured. The infantas had already married, Isabella to Spain and Beatriz to Savoy and the infantes Alfonso and Henrique had been placed in the church since young, but Luis, Ferdinand and Duarte were still unmarried. Joao arranged for Ferdinand’s betrothal to Guiomar Coutinho, 5th Countess of Marialva and 3rd Countess of Loulé, a wealthy heiress of Portugal, and began negotiations with Jaime of Braganza for the hand of his only daughter Dona Isabel to Duarte. Luis was a harder nut to crack, as he was more unwilling to relinquish his bachelorhood, but Joao was determined to find him a bride as well. The king’s own marriage naturally took priority over those of his brothers and while Joao refused to marry until a year had passed from Catherine’s passing, the search began during the winter of 1526.

Portugal was not the only kingdom on a bridal hunt as the search for a bride for the Prince of Wales begun in earnest after the new year’s celebrations of 1527. His first two betrothed had been daughters of Francis I, and while France was still considered an option, Henry and Catherine also looked elsewhere. But Ned was not their only son either; the Duke of York’s betrothal to Katherine Willoughby had been announced during the Christmas festivities in the midst of the Yuletide joy. The eight-year-old boy delighted in being at the center of attention, as he was frequently overshadowed by his elder brother in most occasion. Henry Tudor, or Hal of Nottingham as he was called during his life took after his father the most. Unlike his tall, slender brother, he was shorter and stouter with a round face and a mop of auburn hair. While Ned was no doubt the pride of both his parents, Hal was his father’s delight and as Ned was often away in Wales, it was his brother than got their father’s attention the most. Ned had now reached the esteemed age of eleven and while he loved his brother, he considered himself closer to an adult. His lessons got more advanced and more martially minded; grammar, rhetoric and the study of laws joined hunting, dancing and even sword fighting as Henry wished for his heir to learn the arts of war. No doubt this was also encouraged by Catherine, whom had organised the defence of the kingdom against the Scots in 1513, and she also created a curriculum for Ned that instructed the prince regarding logistics, strategy and field medicine. Her son seemed to take to his lessons like a duck to water in that regard, his master of arms reported that the prince showed signs of becoming a gifted horseman and proficient with the blade.

The king no doubt cherished Mary as well, but given that she was a six years old girl, she got her mother’s attention more. As the only daughter in the family, Catherine devoted considerable time to Mary, especially regarding her education. Mary herself adored Catherine and attached herself to her during ceremonies, as many courtiers commented that she seemed like a miniature queen already. Catherine taught all her children Latin, but Mary was also tutored in dancing and music, such as the virginals and the lute. As she was a precocious girl, Mary performed at Christmas to her parents delight and danced with her brothers. Katherine Willoughby entered the queen’s household at Christmas, as she was to be educated like a royal duchess and she swiftly became one of Mary’s playmates.

During the spring England got several potential offers for the hand of prince Edward from various kingdoms. France offered Madeleine of Valois, or a proxy such as Marie de Bourbon, Marie de Guise and Isabella of Navarre, with the promise that either one of the girls would come with a dowry and trousseau suited for a royal bride. The Duchy of Brabant proposed a match with either Christine of Brabant, or a Dutch proxy such as Anne of Cleves, as duchess Isabella kept close ties with ducal house of Cleves. From Spain came a proposal for the hand of the infanta Isabel, one that Catherine favored greatly. Other suggestions came from various Nordic kingdoms, Elizabeth of Denmark, Birgitta of Sweden and Hedwig of Poland amongst others. The Danish one was immediately rejected, the Swedish one was considered far to low and not interesting to England, but Hedwig was a more interesting concern. Poland and England had little interest in each other, but with enough of a mutual interest perhaps one could be created.

France also made suggestions for Portugal, as Joao III needed a new bride as well. Francis proposed a marriage with Isabella of Navarre, whom had been raised in the court since toddlerhood and Joao gave that match great consideration. Isabella was of royal blood and she would certainly bring a proper dowry to Portugal, but King Ferdinand reacted very strongly upon finding out. The Spanish ambassador made it extremely clear that such a marriage would be considered an offence to them, as it could threaten their own claim on Navarre. Joao thus backed away from that match as peace with Spain was of far more importance. He himself was greatly interested in another french bride; Renée of France. The sister of the late queen Claude had been raised at court and was at this time sixteen years old, thus of marriable age. Her claim to Brittany had been considered one of the reasons Francis was cautious in seeking a suitor to her, but Portugal was not a nation hostile to France. As one of the richest kingdoms in Europe it was a suitable match for France as well, but Francis was still hesitant. Duchess Isabella took that chance to suggest her own candidate to Joao, Anne of Cleves. The duchy and Portugal had long ties since Isabella of Portugal had married Philip the good close to a century ago and it would certainly benefit both kingdoms regarding trade. But Anne was still only twelve years old, while Renée was ripe for the matrimonial bed. The royal council advocated for a marriage with Portugal as well, as it could lead to France gaining influence in the Iberian Peninsula, encourage trade and ally the new Valois-Angouleme House with the House of Avis. Negotiations started in February between the kingdoms and it was finished around May, and Renée was married by proxy to the Portuguese ambassador that stood in for the king at Blois. At the same ceremony Renée surrendered her own claim to Brittany formally before the whole court and signed the necessary document the king had provided. Her trousseau and the first instalment of the dowry would be sent alongside Renée herself, while the rest would be paid over the next few years as Francis promised. The fleet of ships that carried her to Portugal consisted of 27 boats in total, three galleys and two dozen smaller vessels. After a stormy voyage the new queen arrived in Lisbon, green around the gills from seasickness. Queen Renée of France, or

Rainha Renata de Franca as she was hailed meet her husband days later, as she first had to recover from the voyage to Portugal, but once she did her first meeting with Joao went well. Joao was perhaps rather sombre and very religious, but he was kind to his young bride and Renée found him more refreshing than the strutting king of France. Portugal also meant freedom from the awful Louise of Savoy, the king’s overbearing mother and Renée was for the first time the first lady of the court in her own right.

Renée of France, Queen Consort of Portugal in 1528

As all foreign brides, Renée was tasked with upholding the alliance between her native land and her married one, something that became very difficult in that very summer. Mere weeks after her marriage the Duke of Savoy died in the first week of June from a accident, leaving the succession in turmoil: his marriage to Beatriz of Portugal had left behind one surviving child, the three year old Yolande Maria. As the duchy followed salic law, Yolande was inedible to inherit the throne and it was her uncle, Philippe that would now become the next duke. The Count of Genevois had entered the service of King Louis XII and had fought under France at the battle of Agnadello in 1509 and he currently served in the court of Francis I, when the news hit the Valois king. To Francis this was a stroke of fortune as it gave him the opportunity to further increase French influence in Northen Italy and if he played his cards right the path to northern Italy would be completely open. Philippe was promptly summoned to Chambord and it was right before the whole assembled court that he was proclaimed the rightful Duke of Savoy with Francis promising him his support in taking control of his inheritance. To Philippe this was a surprise and he promptly accepted the help of the king, beginning preparations to go to Savoy. But one thing was also on his mind: his bachelorhood. As Philippe was thirty-seven years old at this time and still unmarried, he would need to marry swiftly to ensure that the duchy had heirs. And if Francis wanted to give him an army to secure his duchy, then so he could give him a wife. The king kicked himself in private for marrying Renée to Joao III, had he waited a few weeks more she would have been perfect for Philippe, but he could hardly demand the Queen of Portugal return to France. Renée also noted in her diaries that she

“breathed a sigh of relief of being away from France at this time”. But Renée was not the only lady that Francis could offer to Philippe. Since Savoy also laid near the Duchy of Lorraine and the current duke, Antoine was a close friend of the king, he proposed a marriage with Marie de Guise, the duke’s niece and a scion of one of the most powerful families in France. Philippe had mixed feelings about that match, as Marie was only twelve at this time, but on the other hand she would bring him a dowry and all the support he could need. Her father, the count of Guise was also a very effective general in service to France and a friend of Philippe and Francis. To sweeten the deal, Francis promised to elevate the count to a Duke and to dowry Marie richly. Philippe accepted the arrangement and married his young bride in the first week of July.

The dowager duchess Beatriz was greatly distressed of her brother-in law’s actions and feared for her little daughter’s safety. Charles had left no posthumous child either and she refused to remain in Savoy only to see her own position being usurped by some little

french girl of all things. And Savoy would certainly become a springboard for French ambitions in Italy as well, regardless of the duchy being an imperial fief. Philippe sent a delegation to her in July, in which he declared that she was of course welcome to remain in the duchy as long as she wished and that he would give her and Yolande Marie all the consideration their position demanded. He also asked that she maintained the reins of government until he arrived in Chambéry to take his rightful place as duke along with his new duchess in a few weeks. This set Beatriz’s teeth on edge, as she had no intentions of remaining in a French controlled Savoy, and she begun to pack in secretly. The remainer of her dowry, her possessions, and whatever objects of value in the household was quickly gathered in coffers and chests, alongside with the riches of the royal chapel and smaller pieces of furniture, as well as fabrics, books, jewellery, gold and silver plate, glassware and tapestries. Let his new duchess enjoy the bare rooms upon her arrival. Beatriz would not surrender a single pearl to her. She reached out to the emperor for help as well and their secret correspondence continued in the weeks before the new duke came. The dowager planned her escape in secrecy, as she refused to be parted with her daughter. No doubt Yolande Marie would remain in her uncle’s care, but Beatriz refused to leave her behind. Emperor William was also upset that the imperial fief seemed to be sliding into French control, but as he was currently engulfed in troubles with the duke Ulric regarding the duchy of Wurttemberg at this time, he could only spare enough men to escort her safely from Turin to Bavaria.

“You and your dear daughter are of course welcome to our court in Munich as the king of France seems to have forgotten that the Duke of Savoy are a imperial subject and not one of his.” Emperor William I

When Philippe crossed into Chambéry in the second week of August accompanied by 5,700 French men at arms and knights, he found to his surprise that the ducal castle was empty of not only his sister-in law and niece, but also stripped almost bare. Beatriz had left a fortnight before in the middle of the night, accompanied by some of her household, a few of her husband’s officials that loathed the idea of the French taking over Savoy, including Eustace Chapuys, a rising star in the ducal court and her daughter Yolande. The coffers and chests had been secured to pack mules and wagons that accompanied them to Turin. The Susa Valley where the dowager and her small entourage was traveling was thick with pilgrims along the

Via Francigena, the pilgrimage road that encompassed the distance between the cathedral city of Canterbury in England, cut through France and all the way down to the city of Rome itself. Here she took up residence in the ancient Valentino Castle that was part of her dower, until the imperial escort arrived eight days later and they departed once more for the city of Innsbruck. Philippe found out about the imperial scheme too late; they had already crossed the alps at this point. Her secret flight infuriated him greatly. Not only had she taken his niece unlawfully, but it was a great humiliation to begin his new reign. Marie de Guise was greatly shocked as well, as the glittering castle she had imagined had turned out to be a near bare one in a provincial realm and the situation of her being married to a duke thrice her age far away from the glamorous courts in the Loire Valley. Her letters to her father showed her great distress:

“There is barely a scrap of silk or damask remaining and of silver I can find nothing of value. The dowager seemed to have taken all riches in all of Savoy and I am left with nothing. I fear that this court shall be the poorest in Christendom and I am to be the duchess of paupers, mocked by all.” Beatriz and Yolande arrived in Bavaria with great welcome and was given lodgings in the

Alterhof residence in the city of Munich. They were both frequent visitors to the imperial court and Yolande quickly made friends with the emperor’s only daughter, Helene.

The new duke of Savoy being beholden to France was a worrying prospect to the emperor and as the king would certainly attempt to once more take all of Italy soon with the Savoyard obstacle removed. William turned his gaze to the Sforza family who’s future once again seemed threatened. Francesco II Sforza’s elder brother Massimiliano Maria Sforza was still alive, but he had been held prisoner by France since 1515 and Milan was currently occupied by France. Francesco was still unmarried at the age of thirty-two and that needed to be remedied right away if Milan was to one day return to independence with the Sforza’s. In the late autumn Francesco got an invitation to join the imperial court for Christmas and he accepted. The journey would be shrouded in secrecy to avoid the prying eyes of France, but William had begun to learn the art of subterfuge well. Both Francesco and Beatriz joined the emperor and empress for the festivities, seated next to each other at the table of honor deliberately. If this went the way he planned, then France would get a surprise in the future.

But regardless to king Francis, the year of 1527 had been a very good one indeed. And with Savoy secured, now it was time for another endeavor; the search for a new Queen of France.

Author's Note: So here is a new version of chapter 13. Hopefully it is better than the last one. And with some twists along the way!