You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

Has not been covered yet, but will be in the future.Random question that came to me after I reread the chapters on Manson. I'm assuming that the Heaven's Gate suicide is prevented, but has that been touched upon?

Sounds great! And question man we will get to see more of portugal near the future? maybe a peek at the pretender to the throne?Has not been covered yet, but will be in the future.

I can add Portugal to my list of nations to cover in the next Europe/foreign affairs update.Sounds great! And question man we will get to see more of portugal near the future? maybe a peek at the pretender to the throne?

Great! Since Spain is a monarchy once more i can see the Braganzas getting slowly more support back home to stabalize things.I can add Portugal to my list of nations to cover in the next Europe/foreign affairs update.

Alright then genius, we're looking forward! If you’re going to post it, let's just say on a Friday Evening in your timezone, I'm going to see this on a Saturday Morning in my timezone. I congratulate you on such a lovely match with your girlfriend. Does she know about this alternate timeline that you've been writing for more than six years?No worries.Always happy to give an update when I can! My goal is to try and have the next update published by Friday(?). That day also happens to be mine and my girlfriend's anniversary. If tomorrow is a light day work and school-work wise, then I might be able to post it then.

Thank you! Yes. She's read most of it; and she often gives me feedback and ideas. As I tell my friends and family, she's a keeper.Alright then genius, we're looking forward! If you’re going to post it, let's just say on a Friday Evening in your timezone, I'm going to see this on a Saturday Morning in my timezone. I congratulate you on such a lovely match with your girlfriend. Does she know about this alternate timeline that you've been writing for more than six years?

Mazel ToffThank you! Yes. She's read most of it; and she often gives me feedback and ideas. As I tell my friends and family, she's a keeper.

Impressive! Does she have a favorite chapter that you've written from Acts I, II, and III?Thank you! Yes. She's read most of it; and she often gives me feedback and ideas. As I tell my friends and family, she's a keeper.

Good question!Does she have a favorite chapter that you've written from Acts I, II, and III?

My personal favorites are probably still...

"My Way" - About the final days of JFK's administration as he thinks about cementing his legacy and stepping away from power. Saying goodbye to his presidency was heartfelt, for sure.

"The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face" - Exploring George Romney - a historical figure I knew little about when I first started the TL - and seeing him pass on was very emotional for me.

"Once in a Lifetime" - Again, Reagan vs. R.F. Kennedy is an election I've always wanted to write about.

"The Impossible Dream" - I really enjoyed writing this one.

In general, it's the character drama at the heart of the timeline for me. That's why I keep coming back to this story, year after year.

Oh damn happy early anniversary.No worries.Always happy to give an update when I can! My goal is to try and have the next update published by Friday(?). That day also happens to be mine and my girlfriend's anniversary. If tomorrow is a light day work and school-work wise, then I might be able to post it then.

FWIW I adored Dubya's Vietnam adventures. Are he and Al Gore still friends?Good question!If I get a chance, I'll ask and let you know what she says.

My personal favorites are probably still...

"My Way" - About the final days of JFK's administration as he thinks about cementing his legacy and stepping away from power. Saying goodbye to his presidency was heartfelt, for sure.

"The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face" - Exploring George Romney - a historical figure I knew little about when I first started the TL - and seeing him pass on was very emotional for me.

"Once in a Lifetime" - Again, Reagan vs. R.F. Kennedy is an election I've always wanted to write about.

"The Impossible Dream" - I really enjoyed writing this one.

In general, it's the character drama at the heart of the timeline for me. That's why I keep coming back to this story, year after year.

Are you going to cover the Sri Lankan Civil War at all?Good question!If I get a chance, I'll ask and let you know what she says.

My personal favorites are probably still...

"My Way" - About the final days of JFK's administration as he thinks about cementing his legacy and stepping away from power. Saying goodbye to his presidency was heartfelt, for sure.

"The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face" - Exploring George Romney - a historical figure I knew little about when I first started the TL - and seeing him pass on was very emotional for me.

"Once in a Lifetime" - Again, Reagan vs. R.F. Kennedy is an election I've always wanted to write about.

"The Impossible Dream" - I really enjoyed writing this one.

In general, it's the character drama at the heart of the timeline for me. That's why I keep coming back to this story, year after year.

It is a relatively small-scale conflict, akin to the Troubles, which hit the fan in the 80s and 90s IOTL.

Being of Sri Lankan descent myself, I would also be curious to know this.Are you going to cover the Sri Lankan Civil War at all?

It is a relatively small-scale conflict, akin to the Troubles, which hit the fan in the 80s and 90s IOTL.

Sadly, it is unlikely that TTL Sri Lanka's political trajectory has been butterflied significantly, so the war will still likely happen. I would hope that ITTL it may be resolved by peaceful settlement. That said, it may be better to wait until TTL reaches the mid to late 90s before doing a chapter on Sri Lanka - the conflict was never really a proxy war that same way that other Cold War era conflicts were, so it never drew the attention of major powers until after the end of the Cold War. I see no reason for this to be different ITTL.

Last edited:

If the Portuguese monarchy is restored, Duarte Pio would be enthroned as Duarte II.Great! Since Spain is a monarchy once more i can see the Braganzas getting slowly more support back home to stabalize things.

Exactly! the miguelist would reclaim the throne as the last rightful line for it!If the Portuguese monarchy is restored, Duarte Pio would be enthroned as Duarte II.

Danke schoen!Oh damn happy early anniversary.

Yes indeed. Gore and Dubya maintain a strong friendship, even if they are divided by politics somewhat. At the moment, with Dubya himself working as a business/baseball executive and Gore as a Congressman, they have little reason to butt heads.FWIW I adored Dubya's Vietnam adventures. Are he and Al Gore still friends?

Yes.Are you going to cover the Sri Lankan Civil War at all?

It is a relatively small-scale conflict, akin to the Troubles, which hit the fan in the 80s and 90s IOTL.

I agree with your analysis here. I'll be sure to elaborate once we get there.Being of Sri Lankan descent myself, I would also be curious to know this.

Sadly, it is unlikely that TTL Sri Lanka's political trajectory has been butterflied significantly, so the war will still likely happen. I would hope that ITTL it may be resolved by peaceful settlement. That said, it may be better to wait until TTL reaches the mid to late 90s before doing a chapter on Sri Lanka - the conflict was never really a proxy war that same way that other Cold War era conflicts were, so it never drew the attention of major powers until after the end of the Cold War. I see no reason for this to be different ITTL.

Chapter 149

Chapter 149 - The Tide is High - More American Politics in 1981

Above: The launch of Columbia for STS-2 on April 12th, 1981. The launch represented an opening move in the so-called “Second Space Race” (left); the logo for PATCO, a union representing America’s air-traffic controllers (right). “I'm not the kinda girl who gives up just like that, oh no

It's not the things you do that tease and hurt me bad

But it's the way you do the things you do to me

I'm not the kinda girl who gives up just like that, oh no

The tide is high but I'm holdin' on

I'm gonna be your number one, number one” - “The Tide is High” by Blondie

“It is wonderful to retire while you’re in good health.” - Associate Justice Potter Stewart of the US Supreme Court

“Columbia and its mission embody the pioneer spirit of American optimism. I salute her and her crew on another successful lift-off.” - Robert F. Kennedy

In the 1980 presidential election, the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO), a union, joined with the Air Line Pilots Association and the Teamsters in declining to endorse either major party’s candidate for president.

Unlike the Teamsters, whose refusal to endorse the Democratic Party stemmed from then-Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s history with their former president, Jimmy Hoffa, PATCO’s decision stemmed largely from poor labor relations with the Federal Aviation Administration (the employer of PATCO members) under the Udall administration at that time. Ronald Reagan initially expressed his support for PATCO and its members on the campaign trail, but later distanced himself from labor organizations in general after the media leaked the story of his near-brush with Jimmy Hoffa and an alleged quid pro quo. In any event, Kennedy was elected in November, anyway. Despite his past as a crusader against labor corruption, the president-elect was eager to reassure organized labor that he considered himself their ally.

After the election, but before his inauguration, President-Elect Kennedy wrote a letter to Robert E. Poli, the new president of PATCO. In this letter, Kennedy declared his support for the organization’s demands, and vowed to “fight tirelessly to provide our air traffic controllers with the most modern equipment available, as well as pay and benefits that are commensurate for the invaluable service they provide to our nation’s commerce and national security”. Thus, as Kennedy took the oath of office and settled into his new position in early 1981, PATCO felt confident that the new president was in their corner.

In February 1981, PATCO opened a new round of negotiations with the FAA. Citing concerns for safety, PATCO demanded a 32-hour work week, a $10,000 pay increase for all controllers, better benefits, and a better retirement-package. The talks quickly stalled. In June, the FAA offered a new three-year contract, with more than $100 million up front conversions in raises to be paid out in 12% increases over the next three years; this raise was more than twice what was being offered to other federal employees at the time. This still would have left the average controller’s pay 18% less than their private sector counterparts, however. PATCO balked, demanding further increases and the shortened work week.

That said, PATCO had few practical options to consider.

Unlike most unions, any strike whatsoever by air-traffic controllers, as employees of the federal government, was illegal under the Taft-Hartley Act. Most labor experts warned PATCO’s leaders that pressing ahead with their “unrealistic” demands would be tantamount to “organizational suicide”. Nevertheless, rumors began to spread across Washington that PATCO might attempt to press forward with a strike anyway. The union’s leadership, impressed by the Kennedy letter, felt like the president was likely to side with them over FAA management, especially given his opposition to Taft-Hartley in the first place.

For his part, President Kennedy surveyed the situation closely. Renowned for his empathy, he recognized the grievances among the PATCO members, could sympathize with their dissatisfaction. However, he also understood the urgency of resolving the dispute in a timely manner. To do otherwise might provoke a nationwide crisis. Ever the advocate for social justice and fair labor practices, Kennedy’s commitment to these ideals formed the framework for his approach to resolving the impasse. He knew that a resolution required more than just enforcing the law; it demanded a comprehensive and compassionate strategy.

Above: President Robert F. Kennedy, in a moment of private contemplation shortly before meeting with the negotiators from the FAA and PATCO.

In the days leading up to the strike, Kennedy refrained from immediate punitive measures on the union. Instead, he called for an open dialogue, inviting representatives from both the FAA and PATCO to the White House for negotiations. The negotiations were bound to be intense, with each side presenting their demands in an increasingly histrionic tenor. Kennedy, using his skills as a mediator, sought common ground and proposed compromises that would address the legitimate concerns of both parties.

As the talks got underway, the president took a bold step by appointing a bipartisan commission composed of respected labor leaders, industry experts, and government officials. The commission was tasked with independently reviewing the concerns raised by PATCO and the FAA and proposing recommendations for a fair and sustainable resolution. Kennedy's decision to involve a neutral third party demonstrated his commitment to a just and impartial resolution. The commission held public hearings, aired on C-SPAN (which first began broadcasting in 1979), allowing the voices of both sides to be heard by the public.

When the commission's recommendations were released, Kennedy publicly endorsed them and called on both the FAA and PATCO to accept the proposed terms. The recommendations included compromises on working conditions (including a 40-hour work week), a phased-in approach to wage increases, increased sick and personal time, and a commitment to ongoing dialogue between labor and management in the future. Kennedy's firm endorsement of the commission's recommendations (as well as an unspoken implication that should the union refuse, he might be “forced” to invoke Taft-Hartley and break the strike) created a strong impetus for both parties to come to the table and reach a final agreement. While not everyone was entirely satisfied, the majority recognized the necessity of compromise for the greater good of the nation.

The resolution of the PATCO strike under President Kennedy's leadership marked a turning point in labor relations. Kennedy's approach, rooted in empathy, diplomacy, and a commitment to fairness, set a precedent for addressing complex labor disputes. The air traffic controllers returned to their posts, airports buzzed back to life, and the nation's skies once again remained places of order and safety. It also cemented RFK’s status as a friend of organized labor, and as a successful navigator of treacherous, nuanced political crises.

…

Above: Associate Justice Potter Stewart of the US Supreme Court, circa 1981 (left); Seal of the Supreme Court (right).

Above: Associate Justice Potter Stewart of the US Supreme Court, circa 1981 (left); Seal of the Supreme Court (right).

Shortly before the negotiations to settle the PATCO labor dispute, another inflection point presented itself to President Kennedy.

On June 18th, 1981, Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart announced that he would be retiring from the bench after twenty-three years. He was first appointed to the Court in 1958 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The announcement came as something of a surprise to the Washington establishment and press.

At just sixty-six years old, most assumed that Stewart would want to remain on the Court for at least a few more years. But Stewart insisted that he wanted to retire while he was still physically able to enjoy himself and spend more time with his family. A frequent member of the dissenting minority on both the Warren and Freund Courts, Stewart nevertheless grew more moderate and pragmatic with age. By the time he retired, he was largely seen as a “centrist swing vote”. While on the Court, Stewart made major contributions to criminal justice reform, civil rights, access to the courts, and Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. For many Americans, his expertise would be sorely missed.

Of course, Stewart’s retirement and the vacancy it created presented an opportunity for President Kennedy to make his mark upon the judiciary. It was time for RFK to nominate his first Justice to the Court. While on the campaign trail the year prior, Kennedy had made a number of promises to his supporters vis a vis what he would look for when considering candidates for the Court.

First among these was the candidates’ commitment to the legal precedent set by Doe v. Bolton back in 1973 - that American women had a constitutional right to an abortion under the personal privacy protections granted by the 14th Amendment. Despite his own personal opposition to the practice (informed by his staunch Catholic faith), Kennedy was firmly pro-choice when it came to the law.

Second, the candidates needed to be generally liberal in outlook when it came to civil liberties. Though the 1960s had seen great strides toward greater equality between the races, President Kennedy knew that there was still much work to be done, especially in the field of criminal justice. And with the gay liberation movement maturing into its next phase at the dawn of the 1980s, the emerging LGBT+ community began advocating for greater openness and acceptance of themselves. This marked a contrast to the community’s prior goal of mere “tolerance” by mainstream American society. Though any major moves toward greater rights for queer people would take time and patience to achieve, the movement identified several specific goals they had in mind: striking down so-called “anti-sodomy” laws, which would decriminalize homosexuality nationwide (a process that by 1981 had already begun in multiple states); and recognizing gay marriage, or barring that civil unions, and enshrining the ability to enter into them as a constitutional right.

Third, Kennedy only wanted to consider justices who shared his liberal view on the role of government: to be a positive force for good in American life; a guardian of liberty and justice for all. Finally, if possible, Kennedy believed that it would be “altogether proper” to appoint more justices belonging to historically marginalized groups, including women and people of color.

“The Supreme Court is the court of last appeal for all Americans.” Kennedy remarked privately to his chief of staff, Ken O’Donnell. “It should reflect and represent all Americans”.

Keeping all of these qualifiers in mind, Kennedy thus tasked his advisors (led by Attorney General Charlie Rangel) with drawing up a list of suitable candidates. The list was made; interviews in the Oval Office were scheduled for each of the candidates. One in particular stood out to the president as a strong possible choice.

Above: Patricia Wald, President Robert Kennedy’s first appointee to the US Supreme Court.

Patricia Ann McGowan Wald was born on September 16, 1928, in Torrington, Connecticut. She was the only child of Joseph F. McGowan, an alcoholic, and Margaret O'Keefe. Her father left the family when she was two years old, leaving Wald to be raised by her mother with the support of extended relatives, most of whom were factory workers in Torrington and active union members. Wald had a Roman Catholic upbringing and worked in brass mills as a teenager during the summers to help make ends meet. Due to her involvement in the labor movement and union work, she was determined to go to law school to help protect underprivileged, working-class people.

As a teenager, she attended Torrington’s St. Francis School - a Catholic institution - and then graduated from Torrington’s public high school in 1948 as her class’s valedictorian. She likewise excelled in her undergraduate studies at Connecticut College, joining the Phi Beta Kappa Society and graduating first in her class. She was able to attend Connecticut College for Women only because of a scholarship that she received from an elderly affluent woman from her hometown. She then went on to receive a national fellowship from the Pepsi-Cola Company that allowed her to continue her studies. She would eventually earn her law degree from Yale Law School in 1951. She graduated with only eleven other women that year out of a class of two-hundred. Along with the national fellowship, Wald also paid for law school by working as a waitress and taking research jobs with professors. At Yale, she was an editor on the Yale Law Journal, one of the two women in her class so honored.

In the 1960s, she took various public-sector jobs working in the first Kennedy administration. The book she co-authored in 1964 - Bail in America - helped recommend much needed reforms to the nation’s bail system. She then was appointed to the President's Commission on Crime in the District of Columbia from 1965 to 1966 by President John F. Kennedy. For the rest of JFK’s second term, Wald continued working for his administration in various legal advisory roles, including several years at the Department of Justice. In 1977, President Mo Udall appointed Wald Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. When Justice Wald met with President Robert Kennedy in late June 1981, she was still serving in that position.

RFK admired Wald tremendously. Her work ethic, her determination, her Catholic roots, and most of all, her unyielding pursuit of justice, especially for the less fortunate, made her, in his mind, the ideal candidate. The fact that she would be only the second woman named to the Court (after President George Bush had named Carla Anderson Hills back in 1975) certainly didn’t hurt either. Wald would be the first woman to be appointed to the Court by a Democratic administration, something that seemed important - to show that advancements for women were bipartisan. She enthusiastically accepted and thanked the president for the nomination. Kennedy announced his decision in the Rose Garden on national television shortly before departing for a Fourth of July vacation to Hyannis Port.

Both the media and the political establishment largely praised the pick. A product of a working class upbringing, but who nonetheless boasted an Ivy League education, Justice Wald seemed to represent the best of both worlds. She faced minor scrutiny and even less resistance in the Senate. A few Republicans on the Judiciary Committee expressed “concerns” over Wald’s pro-choice position and her labor friendly views, but the Committee’s chairman was none other than the president’s own brother, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts. Senator Kennedy ensured that his brother’s choice for the Court was swiftly put to the floor for a vote. She was eventually confirmed unanimously (though a few pro-life Senators, including one Donald Rumsfeld of Illinois among others, abstained).

Current Justices (August 1981) - The Freund Court

Chief Justice Paul A. Freund - J.F. Kennedy appointee, since 1968 (Liberal)

Associate Justice Warren Burger - Romney appointee, since 1972 (Conservative)

Associate Justice Byron White - J.F. Kennedy appointee, since 1962. (Moderate)

Associate Justice Arthur Goldberg - J.F. Kennedy appointee, since 1962. (Liberal)

Associate Justice Carla Anderson Hills - Bush appointee, since 1975 (Moderate)

Associate Justice William Rehnquist - Romney appointee, since 1972 (Conservative)

Associate Justice Patricia Wald - R.F. Kennedy appointee, since 1981 (Liberal)

Associate Justice Thurgood Marshall - J.F. Kennedy appointee, since 1967. (Liberal)

Associate Justice William Brennan - Eisenhower appointee, since 1956. (Liberal)

5 - 2 - 2

Justice Wald’s appointment to the Court bolstered an already firm liberal majority on the bench, with only two moderates and two conservatives to balance things out. Though conservative Americans across the country bemoaned this, fearing a continuation of the “activist” courts of Earl Warren and Paul Fruend, liberals and progressives were thrilled. President Kennedy had scored another major victory in his first year in office.

…

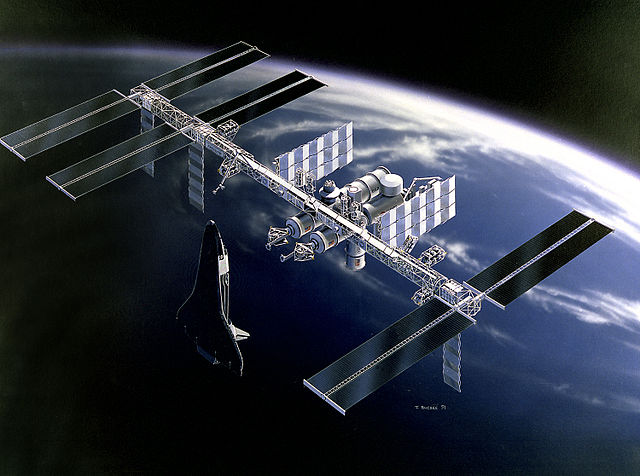

Above: NASA’s logo (left); Artist’s rendering for Freedom - the permanently crewed, Earth-orbiting Space Station designed by NASA as the first “way stop” to further exploration of the cosmos in the Second Space Race (right). Another area of rapid development in the first year of RFK’s term was space exploration.

The president knew all too well that, in the popular imagination, the joint American-Soviet moon landings (the culmination of the Apollo-Svarog missions) were arguably the crowning achievement of his brother’s presidency. Indeed, they might well be the pinnacle of human exploration to that time. They were thought of as a throwback to a simpler time, when the USSR and the USA collaborated on advancement together - for all mankind. But no more.

With Cold War tensions once more on the rise and the A-S missions now a fleeting memory, NASA marched on. In President Kennedy’s mind, he needed to emulate Jack once more, and go one step further: seriously proposing a manned mission to Mars. He would ultimately do this in his first State of the Union address, delivered on January 26th, 1982. In that speech, Kennedy declared, “We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful economic and scientific gain, for the betterment of man.”

But even before that, NASA continued the work it had begun under the Udall administration, namely, work on the design, fabrication, and launch of Freedom - the permanently crewed, Earth-orbiting Space Station designed by NASA as the first “way stop” to further exploration. This was considered by NASA administrator James M. Beggs to be “the next logical step” in space. NASA hoped for the station to function as an orbiting repair shop for satellites, an assembly point for spacecraft, an observation post for astronomers, a microgravity laboratory for scientists, and a microgravity factory for companies.

Following the presidential announcement of the station by President Udall in 1980, NASA began a set of studies to determine the potential uses for the space station, both in research and in industry, in the U.S. or overseas. This led to the creation of a database of thousands of possible missions and payloads; studies were also carried out with a view to supporting potential planetary missions, as well as those in low Earth orbit.

Unfortunately, progress was slow going and expensive.

While the Space Shuttle turned out to be successful in its proposed role as a “space truck” to deliver crews and materials into orbit, the creation and estimated maintenance costs on the space station itself proved somewhat daunting. Beggs and other NASA officials informed the president and sympathetic members of Congress (including Senator John Glenn and other former astronauts) that unless “other sources” of funding were acquired, NASA’s budget would need to balloon drastically in order to see the station completed. Kennedy recalled another reason that Jack had brought the Soviets in on the moonshot: cost-sharing.

Thus, RFK devised a similar notion to help finance Freedom without undoing the good work he’d done erasing the deficit: rope in America’s allies. Over the next several years, Freedom would become a multi-national collaborative project, ultimately involving four space agencies: NASA (United States); NASDA (Japan); ESA (Europe) and the CSA (Canada). This had the added benefit of reinforcing America’s relationships with several of its close allies, just as the Soviet’s attempted answer to Freedom, Equality was grounded and quagmired in development Hell.

Though the station was still several years from lift-off in 1981, right from the get-go, President Kennedy set it off to a strong start.

…

Above: Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV), as seen under a microscope. The disease, which can cause the condition known as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) was first identified in the United States in 1981. On June 5th, 1981, The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) published an article in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR): “Pneumocystis Pneumonia - Los Angeles.”

The article described cases of a rare lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), in five young, previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles, California. Los Angeles immunologist Dr. Michael Gottlieb, CDC’s Dr. Wayne Shandera, and their colleagues reported that all the men had other unusual infections as well, indicating that their immune systems were not working properly. Two had already died by the time the report was published and the others would die soon after. This edition of the MMWR marks the first official reporting of what will later become known as the AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) epidemic.

The same day that the MMWR was published, New York dermatologist Dr. Alvin Friedman-Kien called CDC to report a cluster of cases of a rare and unusually aggressive cancer - Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) - among gay men in New York and California. Like PCP, KS is often associated with people who have weakened immune systems.

In the days that followed, The Associated Press, the Los Angeles Times, and the San Francisco Chronicle reported on the MMWR article. Within days, CDC received reports from across the nation of similar cases of PCP, KS, and other opportunistic infections, specifically among gay men.

In response to these reports, the CDC established the Task Force on Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections to identify risk factors and to develop a case definition for the as-yet-unnamed syndrome so that CDC can begin national surveillance of new cases.

On the 16th, a 33-year-old, white gay man who was exhibiting symptoms of severe immunodeficiency became the first person with AIDS to be admitted to the Clinical Center at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Unfortunately, he would never leave the Center and died on October 28th.

Throughout the summer, the CDC and journalists continued to track the story, especially in epicenters of the gay community, including New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Due to a lack of scientific understanding and available information at the time, newspapers generally advised the gay and lesbian community to see their physicians if they experienced “shortness of breath” and other symptoms of possible immunodeficiency. Unfortunately, where there is ignorance is not a vacuum. Where there is ignorance, there is often misinformation and misunderstanding.

Due to early cases of the disease predominantly appearing in the LGBT+ community, the public’s perception of AIDS was, at least initially, that it was something that only affected “the gays”. This was not at all helped when the New York Times published an article titled, “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals'' on July 3rd. This term - “gay cancer” - entered the public lexicon.

Acclaimed writer and film producer Larry Kramer held a meeting of over 80 gay men in his New York City apartment to discuss the burgeoning epidemic. Kramer invited Dr. Friedman-Kien to speak; the doctor asked the group to contribute money to support his research because he had no access to rapid funding. The plea raises $6,635, but this will not be anywhere near enough. Kramer, unwilling to take the issue lying down, decided to lobby the federal government, and in particular the administration, for help. By calling in a number of favors from contacts in the entertainment industry, (namely, Judy Garland), Kramer and Dr. Friedman-Kien were able to secure a meeting with the president on August 28th. Of the 108 cases reported by then, 107 were male; 94% of those whose sexual orientation were known were gay/bisexual; and 40% of all patients had already died.

Heading into the meeting, President Kennedy was immediately concerned. He’d been briefed on this strange new disease by Secretary of Health and Human Services Patricia R. Harris shortly after it first emerged. From a medical standpoint, it especially worried Kennedy. A disease which, at the time, could be spread by unknown means that appeared to cause the rapid and apparently irreversible breakdown of the patient’s immune system? The prospect of an epidemic of that nature was terrifying.

Kennedy’s opinions on homosexuality and with them, his relationship with the LGBT+ community, had also shifted a great deal throughout the course of his life.

As a man born in the mid-1920s, Kennedy grew up in a world in which homophobia was taken as a matter of course. Any type of deviation from heteronormativity was treated with outright derision, scorn, and even as a psychiatric condition. Homosexual relations were (and in many places as of 1981 continued to be) outright criminalized. The Catholic church that Kennedy held so dear likewise condemned homosexual relations as “sinful” and “unnatural”. Such acts went against the very nature of humankind as passed down by the Lord God since the time of creation. As a boy and later, a young man, Kennedy was often guilty of using homophobic language, even slurs. Raised in the traditional Irish view of masculinity, he saw homosexuality as “effeminate” and “emasculating”. He felt confused by it, and thus, disliked it.

And yet… Kennedy was also capable of immense growth and change. A deeply empathetic person, the future president found himself coming to understand queer people the more that he got to know them.

Lem Billings, a boyhood companion of his brother Jack, and thus, a lifelong family friend, was gay. Though Billings would remain in the closet until the mid-1970s, he did not hide his sexuality from the Kennedys. Lem harbored romantic feelings for Jack throughout their teenage years and twenties, but these went unrequited. Eventually, he settled for platonic friendship. Despite being well aware of his friend’s sexuality, Jack never made light of it; whenever Bobby or Ted did, he sternly corrected them for it.

Above: Jack Kennedy and Lem Billings (and a puppy) in their youth in the 1930s.

“Lem is my friend. He’s not really so different from you or me.” Jack told Bobby once. “That’s all there is to it.”

The older that Bob Kennedy got, the more he was exposed to people who were different from him. During the Lavender Scare in the 1950s, he heard horror stories of men (and some women) having their lives ruined when they were forced out of the closet. Many lost their jobs, and even their lives, via suicide. Bobby came to realize that he mistreated homosexual men and women the same way that others had mistreated the Kennedys for their Irish roots and Catholic faith. People feared what they did not understand. The only antidote for ignorance is knowledge and wisdom.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, despite remaining a pillar of social conservatism and traditional values in his personal life, he continued to grow more and more accepting of gay, lesbian, and other queer people and their right to exist and live their lives.

By the time of his 1980 campaign for president, Kennedy openly sought the endorsement of the Rainbow Coalition and other gay and lesbian activist groups. He considered Congressman Harvey Milk (D - CA) a friend and ally, and believed that the time had come for greater toleration of LGBT+ people in the United States. Though this process would and needed to be gradual (in Kennedy’s mind at least), it needed to begin just the same.

Thus, when Larry Kramer and Dr. Friedman-Kien headed to the White House on August 28th, 1981, they encountered not an unsympathetic enemy, but an ally. The president heard their pleas and agreed to use the power of his office to do something about it.

Kennedy ordered the Department of Health and Human Services to immediately free up “all possible funds'' to research what he called “the immunodeficiency epidemic”. He also promised to earmark additional funding in the budget for fiscal year 1982 to continue research and work on a possible cure if the epidemic continued. When announcing this decision, and when asked about it by reporters during press briefings, the president described the developing epidemic as a “burgeoning public health crisis”. His use of the word “crisis” was deeply appreciated by Kramer and other LGBT+ activists, who felt relieved that the administration was treating the disease with the level of seriousness that the situation warranted.

Of course there were many in Washington, particularly among the Republican opposition, but also Democrats, and even some of the president’s own political advisors, who disagreed with Kennedy’s handling of the situation. Republicans, especially conservative firebrands, wanted to turn “AIDS” into a culture war issue.

Gleefully referring to the disease as “gay cancer”, Senator Jesse Helms (R - NC), expressed his belief on the floor of the Senate that AIDS was the “smiting hand of God, come to punish homosexuals for living lives of sin and abomination”. Helms’ comments drew widespread criticism from both activists and the mainstream media. But, as Kennedy’s political advisors pointed out, many millions of Americans agreed with Helms’ view.

Chief of Staff Ken O’Donnell, though not particularly homophobic himself, warned the president that only a slim majority of the public supported even decriminalization and toleration of homosexuality.

This would later be famously represented by the January 27th, 1983 episode of the popular sitcom Cheers - “The Boys in the Bar” - which depicted Sam Malone (Ted Danson)’s former Red Sox teammate - Tom - coming out as gay, then having to defend Tom (with the help of Diane) from the bar’s homophobic regulars, including Norm, who fear that Tom will “turn the place into a gay bar”. Though Sam, Diane, and Tom triumph in the end, with most of the patrons coming around to treating Tom as “one of the guys”, many viewers wrote angry letters to NBC following the episode’s airing, and expressing their sympathy with Norm’s homophobic views.

According to polling done by the National Opinion Research Center in 1980, 82.5% of Americans opposed the legalization of same-sex marriage. Only 10.8% supported it. The rest said they “did not know” or “did not have an opinion”. Obviously, such a reform would require a monumental shift in public opinion. Thus, for now, Kennedy and his allies in the LGBT+ community continue to advocate for awareness, toleration, and greater acceptance. Again, progress would be slow and painful. But it will come.

In the meantime, President Kennedy fired back at his critics that regardless of whether the victims of the AIDS epidemic were gay or not, they “were still human beings”. They “deserved the same dignity and respect as every other person”. He invoked the teachings of Christ and the “golden rule”, asking the American people to consider, “How would you want the nation to respond if a disease emerged that seemed to disproportionately affect a community of which you happened to be a part?”

Though “gay baiting” would continue to provide fodder for right-wing pundits and editorialists in their response to the AIDS crisis and President Kennedy’s handling of it, the left (especially media centers in New York and Hollywood) fought back as well. Even Gore Vidal, “new left” public intellectual and known detractor of the Kennedy family, came out in support of the president’s actions on this issue.

As the epidemic continued to spread throughout the year, it began affecting drug users and prostitutes, as well as their children. The further the issue spread, the less it came to be associated with the gay community in particular. As the decade (and research into the disease continued), President Kennedy’s stance slowly became more and more common until it was held by the majority of people. Kennedy also helped to “normalize” the disease and combat paranoia and misinformation about it by visiting patients afflicted with HIV/AIDS in the hospital and being photographed shaking their hands and praying with them.

It would, unfortunately, be several years before significant headway was made on fighting the disease. But at least with the full support of the Kennedy administration, every possible effort was being made to combat it.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: RFK’s First Year of Foreign Policy

Good to see RFK tackling AIDS and progress towards LGBT+ acceptance/toleration.

I wonder, will Gore Vidal win the 1982 California Senate Democratic primary and Senate election? If so then he could be a future presidential candidate.Even Gore Vidal, “new left” public intellectual and known detractor of the Kennedy family, came out in support of the president’s actions on this issue.

Share: