I hadn't heard about that. Saw him at one of his crusade events when it stopped in my hometown in the early 2000's. One of the few evangelists I admired.So, this is a just a suggestion based on something I found out recently.

Apparently when The Exorcist came out, Linda Blair essentially became a lightning rod for much of the controversy, with Billy Graham apparently openly accusing her of glorifying Satan. She got so many death threats her parents had to hire bodyguards.

With the "And so have I" movement going on, could we maybe see Billy Graham actually face some form of consequences for contributing to a teenager getting death threats?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

I still believe Graham is one of the few admirable televangelists out there, but I do wish that he faced some form of consequences for doing his part in what happened.I hadn't heard about that. Saw him at one of his crusade events when it stopped in my hometown in the early 2000's. One of the few evangelists I admired.

Or at least for him to admit he was wrong and apologize. I mean it wouldn't be the first time he would apologize publicly for something.I still believe Graham is one of the few admirable televangelists out there, but I do wish that he faced some form of consequences for doing his part in what happened.

So, this is a just a suggestion based on something I found out recently.

Apparently when The Exorcist came out, Linda Blair essentially became a lightning rod for much of the controversy, with Billy Graham apparently openly accusing her of glorifying Satan. She got so many death threats that her parents had to hire bodyguards.

With the So Have I Movement going on ITTL, could we maybe see Billy Graham actually face some form of consequences for contributing to a teenager getting death threats?

Oh yeah I forgot about that. Billy Graham certainly was an "interesting character." I hope Linda has had a much better time than she did IOTL.

I'll admit it was actually disappointing to learn that, mostly because he seemed to actually be a moral man in comparison to many other televangelists. I mean, he was an outspoken advocate for Civil Rights during the 60's, and my understanding is that MLK considered him a friend.

It's messed up to learn he essentially contributed to a twelve year old getting death threats.

I hadn't heard about that. Saw him at one of his crusade events when it stopped in my hometown in the Early 2000's. One of the few evangelists I admired.

I still believe Billy Graham is one of the few admirable televangelists out there, but I do wish that he faced some form of consequences for doing his part in what happened.

I've never heard this side on Billy Graham, in addition of having opposed views towards Jews, Feminism, Abortion, and Homosexuality. What would be his reaction to JFK's Assassination Attempt, JFK's Visit to USSR, American Conservative Party by Falwell and Wallace, MLK's Assassination Attempt, Guaranteed Universal Income, The Cambodian War, The Manson Murders, The Hoover Affair, The Assassination of President Romney, Doe v. Bolton, Equal Rights Amendment, Universal Healthcare Act, So Have I Movement, and RFK's Assassination Attempt ITTL?Or at least for him to admit he was wrong and apologize.

I've also learned that he's a lifelong registered member of the Democratic Party that he opposed the candidacy of JFK in the 1960 US Presidential Election IOTL due to him being Roman Catholic. Now I'm wondering what would be his relationship with JFK now that he survived from the assassination attempt in 1963, got reelected in 1964, and complete his two terms in office in 1969 ITTL? He has close relations with President Eisenhower, Vice President Johnson, State Secretary Nixon, Vice President Reagan, MLK, even Queen Elizabeth II. I wonder what would be his relations with Presidents Romney, Bush, Udall, and RFK during their times in office ITTL?

To think on him being criticized was impossible because he's untouchable. One of The Greatest and Most Admired Americans, Famous Televangelist, an Advisor and Pastor to every US Presidents since Truman, Supporter of the Civil Rights Movement, and has a Close Relations with The Queen of England, was about to face another challenge of his life. With the So Have I Movement in it's early years, I'm wondering what would happen to him ITTL? Would he be fall from grace like his fellow televangelist Jerry Falwell or he would admit and apologize for his mistakes in the past and be forgived by all Americans and the rest of the world? We'll be looking forward for him in the next update Mr. President and please give us your response on how would he face his consequences.

Last edited:

I can imagine him still having a close relationship with JFK I mean after he was elected they became friends. I can also see him become hesitant towards Romney because of him being a Mormon. He probably has a cordial relationship with George H.W. Bush. He would probably have been a little weary of Mo Udall since the guy was not exactly a very religious man. In RFK Graham would probably find someone on the same scale of spiritual and religiousness as himself owing to RFK's devout Catholicism.I've never heard this side on Billy Graham, in addition of having opposed views towards Jews, Feminism, Abortion, and Homosexuality. What would be his reaction to JFK's Assassination Attempt, JFK's Visit to USSR, American Conservative Party by Falwell and Wallace, MLK's Assassination Attempt, Guaranteed Universal Income, The Cambodian War, The Manson Murders, The Hoover Affair, The Assassination of President Romney, Doe v. Bolton, Equal Rights Amendment, Universal Healthcare Act, So Have I Movement, and RFK's Assassination Attempt ITTL?

I've also learned that he's a lifelong registered member of the Democratic Party that he opposed the candidacy of JFK in the 1960 US Presidential Election IOTL due to him being Roman Catholic. Now I'm wondering what would be his relationship with JFK now that he survived from the assassination attempt, got reelected, and complete his two terms in office ITTL? He has close relations with President Eisenhower, Vice President Johnson, State Secretary Nixon, Vice President Reagan, MLK, even Queen Elizabeth II. I wonder what would be his relations with Presidents Romney, Bush, Udall, and RFK during their times in office ITTL?

With the So Have I Movement in it's early years, I'm wondering what would happen to him ITTL?

As for how he would react to policies, I'm not quite sure. He'd probably see the Cambodian conflict as a righteous cause against communism. I could see him be somewhat dismayed by the tactics of Hoover as FBI director, especially in his survelliance of MLK Jr.

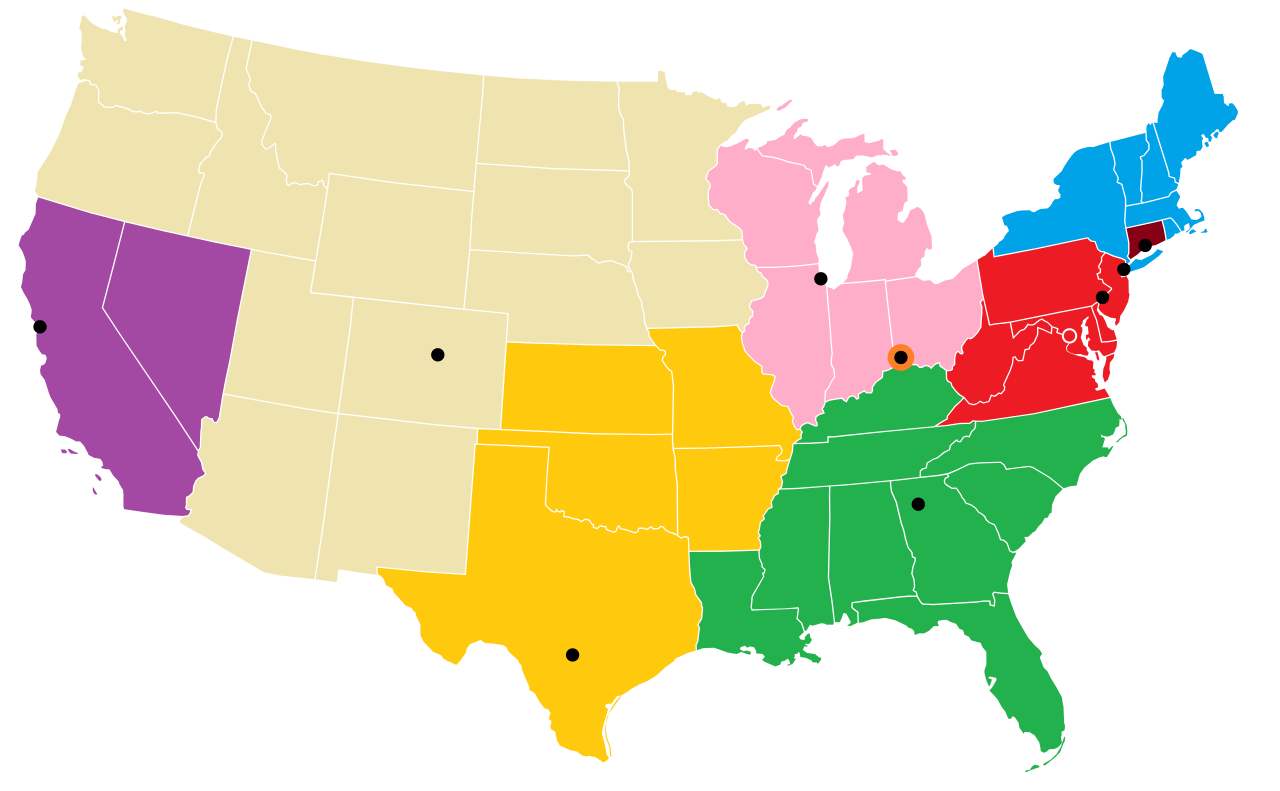

Looking at this map a little closer, there isn't an explanation of what the deal with Connecticut is in maroon, or why Cincinnati has an orange ring around it. Oh, and what company has jurisdiction over Hawaii and Alaska?On January 8th, 1982, just under a year into President Kennedy’s first term in office, the US District Court for the District of Columbia settled a ruling in United States v. AT&T. After nearly a decade of legal wrangling, the progressives finally had their way. And after more than a century of monopoly, AT&T (aka “Ma Bell”) would, in exchange for being allowed to enter the computer business, be broken up into seven independent companies, colloquially known as "Baby Bells".

Above: Map of the seven “baby Bells” created by the breakup of “Ma Bell” in 1982. They were: “US West” (Gray); “Pacific Telesis” (Purple); “Southwestern Bell Corporation” (Yellow); “BellSouth” (Green); “Ameritech” (Pink); “Bell Atlantic” (Red); and “NYNEX” (Blue).

This is some top-tier analysis. I agree with all of these takes. Thank you for your contribution to the conversation!Out of all the races, there are a few that make me think that it could be either one or two seat pickups or declines, with the key races being the following:

Nebraska: Ed Zorinsky was a notable conservative Democrat that had a lot of cajoling and courting to return to the party he switched from. Depending on the Kennedy Administration's agenda as well as whatever appeals Russell Long can soothe him over will be vital

Wyoming: A Kennedy liberal in a state so red, it's almost concerning and winning against a Republican that hit the rural world that is Wyoming; I wouldn't be surprised if there was an effort to get Dickie into the seat for a GOP gain

Texas: *looks up Audie Murphy* Even in a state like Texas with a WW2 hero, I could see him facing some trouble; maybe he stays, but it's more a lean Dem seat

Oregon: Packwood, with the "So Have I" movement, almost makes him the prime seat for Democrats if he is forced to resign earlier than OTL

Florida: Hawkins could be as vulnerable as she is strange, but it depends on who's the Democrat in 1982 and if bucking the trend could help them in a state like Florida

California: Tunney, unless he's retiring, is set in there; would be interesting, however, if there's a Jerry Brown Senate career

Connecticut: Weicker could survive, unless Bobby is set on eliminating moderate Republicans to help sink the GOP in going full on conservative

Maryland: Mathias could very well be a Dem pickup if the goal is to eliminate one of the most notorious Rockefeller Republicans

As much as I could see a buck trend of the incumbent winning seats, I could easily see the GOP making some form of inroads with the right candidates. All in all, I could say a net pickup of one

Interesting suggestion. I agree that Billy Graham will likely have to reckon with several of his less savory takes from OTL here. While the "Christian left" will remain a more active political force ITTL, I still see the pendulum swinging away from evangelicals on social issues like LGBT+ rights and abortion long term.So, this is a just a suggestion based on something I found out recently.

Apparently when The Exorcist came out, Linda Blair essentially became a lightning rod for much of the controversy, with Billy Graham apparently openly accusing her of glorifying Satan. She got so many death threats her parents had to hire bodyguards.

With the "And so have I" movement going on, could we maybe see Billy Graham actually face some form of consequences for contributing to a teenager getting death threats?

Good questions! I believe Connecticut is maroon because there were disputes over whether Bell Atlantic or NYNEX would cover the state (please correct me if someone knows that's incorrect?). Orange around Cincinnati I am not sure, unfortunately. This was just a map of the "Baby Bells" from OTL that I found and thought would make sense to use. Not sure about Alaska and Hawaii IOTL, but ITTL, they are under the jurisdiction of Pacific Telesis.Looking at this map a little closer, there isn't an explanation of what the deal with Connecticut is in maroon, or why Cincinnati has an orange ring around it. Oh, and what company has jurisdiction over Hawaii and Alaska?

Chapter 155

Chapter 155 - Who Can it Be Now?: (Another) Changing of the Guard in Moscow

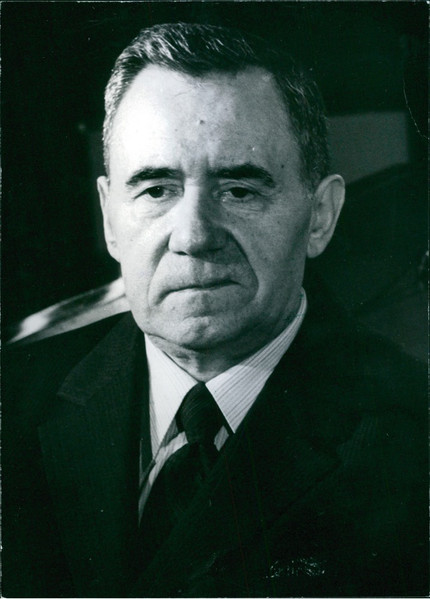

Above: The view from Red Square - state funeral for Mikhail Suslov, January 28th, 1982 (left); Grigory Romanov, Suslov’s eventual successor as Chairman of the Presidium and First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (right). “Who can it be knocking at my door?

Go 'way, don't come 'round here no more

Can't you see that it's late at night?

I'm very tired and I'm not feeling right

All I wish is to be alone

Stay away, don't you invade my home

Best off if you hang outside

Don't come in, I'll only run and hide

Who can it be now?

Who can it be now?

Who can it be now?

Who can it be now?” - “Who Can it Be Now?” by Men at Work

“Sometimes, history needs a push.” - Vladimir Lenin

The rise of Solidarity in Poland (and the political and economic turmoil it portented) created another “crisis of confidence” in the Kremlin. The authority of the Polish United Workers’ Party (that country’s ruling communist party) eroded significantly, and there were some in Moscow who feared that Poland might break away from Soviet-style communism altogether. Acting in his role as head of the Politburo, First Secretary Mikhail Suslov created (and subsequently chaired) a commission on how to handle the “Polish situation”.

Beginning on August 28th, 1980, the commission began to consider Soviet military intervention in order to “stabilize” the region. This course of action was favored by defense minister Ustinov, but opposed by Suslov and Gromyko, the other members of the “troika” leading the USSR at that time. It was also opposed by Wojciech Jaruzelski, First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party. Jaruzelski was able to persuade the commission that a Soviet military intervention would only aggravate the situation.

Suslov would write of his decision not to send in the tanks, “If troops are introduced, that will mean a catastrophe. I think that we all share the unanimous opinion here that there can be no discussion of any introduction of troops.” The First Secretary did manage to persuade Jaruzelski to declare martial law in his country until the situation could be contained, however.

The election of Robert F. Kennedy to the presidency of the United States posed a further problem for Moscow. Though both candidates had been hawkish on the campaign trail (by American standards), the troika had strongly hoped for a victory by Ronald Reagan. Reagan was seen as a “lightweight” on foreign affairs, whom the troika and their allies could have “dealt with quite easily”. After all, his inflammatory rhetoric would have made him look, in Gromyko’s words, “like a buffoon” on the international stage. Bob Kennedy, on the other hand, was well-known in Moscow for his “cutthroat nature” and “ruthlessness” while simultaneously enjoying widespread respect and stature abroad. Under Kennedy, the US would once again begin to seriously challenge Soviet influence across the globe.

Suslov made plans for how to “counter” Kennedy, especially after the American president survived the attempt on his life by Mark Chapman, but before the Kremlin could enact them, Suslov developed a coronary thrombosis - the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. Four days later, on January 25th, 1982, Suslov died of arteriosclerosis and diabetes just after four in the afternoon, Moscow time. He was 79 years old.

Though little mourned by the Soviet public, Suslov would be missed dearly by many on the politburo. He was widely regarded as the party’s foremost expert on Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy and theory, a true ideologue, committed to communist revolution.

In the immediate aftermath of Suslov’s death, Konstantin Chernenko - his deputy - ascended to the position of “Acting Chairman of the Presidium and Acting First Secretary” until such time as mourning for Suslov could be completed and a new Chairman chosen. Chernenko himself was no spring chicken, already 70 years old in January 1982 and reportedly in poor health. During Suslov’s funeral, Chernenko struggled to be heard, even while mic'd, as he read the eulogy. Chernenko was also ethnically Ukrainian; not a deal breaker for a Soviet leader, but, by the unspoken rules of Russian supremacy within the USSR, not ideal.

At the time of his ascent to the country's top post, Chernenko was primarily viewed (as Suslov himself had been) as a transitional leader who could give the Politburo's "Old Guard" time to choose an acceptable candidate from the next generation of Soviet leadership. By this time, they had already more or less settled on their man: Grigory Vasilyevich Romanov.

Romanov was born on February 7th, 1923 in Novgorod Governorate into a peasant family. Romanov served as a soldier in the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War (World War II). Romanov later joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1944. He graduated from the Leningrad Shipbuilding Institute in 1953, and became a designer in a shipyard. He fulfilled several important posts in the party committee of the enterprise he was working at and later in the Leningrad city and regional party committees. In September 1970 he was elected as First Secretary of the Communist Party Committee of the Leningrad Region. In this position, he gained a reputation of being a skilled organizer and well versed in economic matters, winning defense investment for Leningrad over other regions and attracting the attention of the party’s upper echelon, including Yuri Andropov, who subsequently brought him to Moscow and helped promote him in June 1979 to the very prestigious and influential post of a secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU responsible for industry and the military-industrial complex. Throughout the last few months of Andropov’s tenure, Romanov became seen as one of his closest allies.

Indeed, contrary to subsequent evaluations of Romanov by both western observers and the hardliners themselves, it is perhaps more accurate to describe Romanov as a “moderate” than a “conservative”. An ardent supporter of Andropov's comprehensive program for the reform, renewal, and further development of socialism in the Soviet Union and beyond, Romanov simply believed in the Andropov style of reform (economy-first) in contrast with others, such as Gorbachev and Tereshkova, who also favored various degrees of political liberalization.

What Romanov succeeded in, however, was blending in with whatever group he found himself in politically. He made himself into a chameleon, shifting his rhetoric to placate and woo whatever faction he happened to be speaking to at any given time. This, combined with their perception of him as “sympathetic to conservative views” led Chernenko, Ustinov, and Gromyko to favor Romanov as the Union’s next leader.

Following the four days of mourning prescribed by the Soviet constitution after Suslov’s death, Chernenko summoned the politburo and put forth the motion to name Romanov to all positions of leadership. Some questioned the wisdom of handing power to this relative “newcomer”. After all, Romanov had only been a member of the central committee for the last two and a half years. If nominated, his would be the most rapid ascent in the history of Soviet politics. At 57 years old, he was the second youngest member of that body (ahead of just Mikhail Gorbachev - 49). But Ustinov and Gromyko supported the move, believing that not only was Romanov “one of them”, but also that they could “mold” this “naive newcomer” into governing as they saw fit. With any resistance to the motion, tokenistic or hidden (as was the case of Gorbachev), the motion passed. Grigory Romanov became the first leader of the Soviet Union to have been born after the Revolutions of 1917. This was truly a watershed moment in Soviet history and politics.

Somewhat insecure in his new role, Romanov did not rock the boat immediately after entering office. By the beginning of 1982, the stagnation of the Soviet economy was obvious, as evidenced by the fact that the Soviet Union had been importing increasing amounts of grain from the U.S. throughout the 1970s. As soon as President Robert F. Kennedy revoked the grain embargo, the Soviets not only resumed their orders, but increased them. This staved off popular revolt over the availability of bread and other essential goods, but did little to improve the Soviet Union’s prestige and influence abroad. Again, Romanov, like his mentor Andropov, understood the need for reform, but the economic system was so firmly entrenched that any real change seemed impossible.

Eschewing any radical economic or political reforms then, Romanov’s immediate domestic policy leaned heavily toward “restoring discipline and order” to Soviet society. He promoted a small degree of candor in politics and mild economic experiments similar to those that had been associated with the late Alexei Kosygin's initiatives in the mid to late 1960s. Simultaneously, he launched an anti-corruption drive that reached high into the government and party ranks. In an attempt to “model” his new ideal for Soviet leadership, Romanov lived modestly. Eschewing the "decadent dachas" of his predecessors, he favored a simple townhouse in Moscow. He began a public relations campaign to show himself as a “new” kind of leader: professional; efficient; and able to restore the Soviet Union to its “rightful place in the world”.

Unfortunately, the new leader’s situation abroad was no better.

Romanov immediately faced a series of foreign policy crises: the hopeless situation of the Soviet army in Afghanistan; the aforementioned threat of revolt in Poland; growing animosity with the People’s Republic of China under Hu Yaobang; the Iran-UAR war in the Middle East; and brewing trouble in eastern and southern Africa.

Above: Soviet troops battle insurgents in Afghanistan, circa 1982 (left); Mujahideen rebels, also circa 1982 (right).

By 1982, the Soviet military presence in Afghanistan had increased to approximately 125,000 soldiers as fighting across the country intensified. The complication of the war effort gradually inflicted a higher and higher cost on the Soviet Union’s treasury as military, economic, and political resources became increasingly exhausted. Despite the best efforts of both the Soviets and their allied communist regime in Kabul, resistance to their control over the country not only persisted, but intensified.

To begin with, the political situation shifted, first in 1977, when Pakistan (the USSR’s ally in the invasion) withdrew from the conflict following new elections, which saw the ruling PPP’s leader toppled from power, replaced with an antiwar prime minister. The new Pakistani government renounced their previous war-aim of founding a “client state” of “Pashtunistan” and instead welcomed “any Pashtuns who wished to join Pakistan” to do so. With the withdrawal of Pakistan, many ethnic Pashtuns no longer saw the invading Soviets as their defenders or liberators, and instead began switching sides, joining and supporting various resistance groups. The conflict took on an increasingly religious tone for the Afghani people, who saw the Soviets as “godless communists”, hell bent on subjugating their country to “forced secularization and imperial domination” from Moscow.

Though the resistance groups were by no means united (they fought amongst themselves almost as much as they fought the Soviets), they held a number of key advantages over the invaders.

First, most of the resistance fighters were either from Afghanistan or had at least lived in the country for several years. They were thus far more familiar with the country’s mountainous geography than the Soviets. They fought with a mix of religious zeal and national fervor, willing to give anything, including their lives, to defend their home. Finally, since 1975, the rebel groups had been receiving aid in the form of financial support, arms, supplies, and military training from a coalition of states, including: the United Kingdom; Saudi Arabia; and, mostly through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the United States.

President George Bush famously called the Mujahedeen “freedom fighters”, a phrase which would be repeated by Ronald Reagan on the campaign trail in 1980. While Mo Udall had felt “uneasy” about arming and aiding them directly, when Robert Kennedy took the oath of office in 1981, he did not share Udall’s reservations. Though Kennedy did not arm just anybody looking for American resources (he explicitly forbade the CIA and its director, former head of Naval Intelligence and Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, from meeting with anyone but indigenous Afghan mujahedeen, let alone arming, training, coaching, or indoctrinating them), he did authorize nearly $5 billion in aid throughout the course of the program - codenamed Operation Hurricane. This was all part of his administration’s renewed commitment to “containment”, as opposed to the “détente” of the last decade and a half.

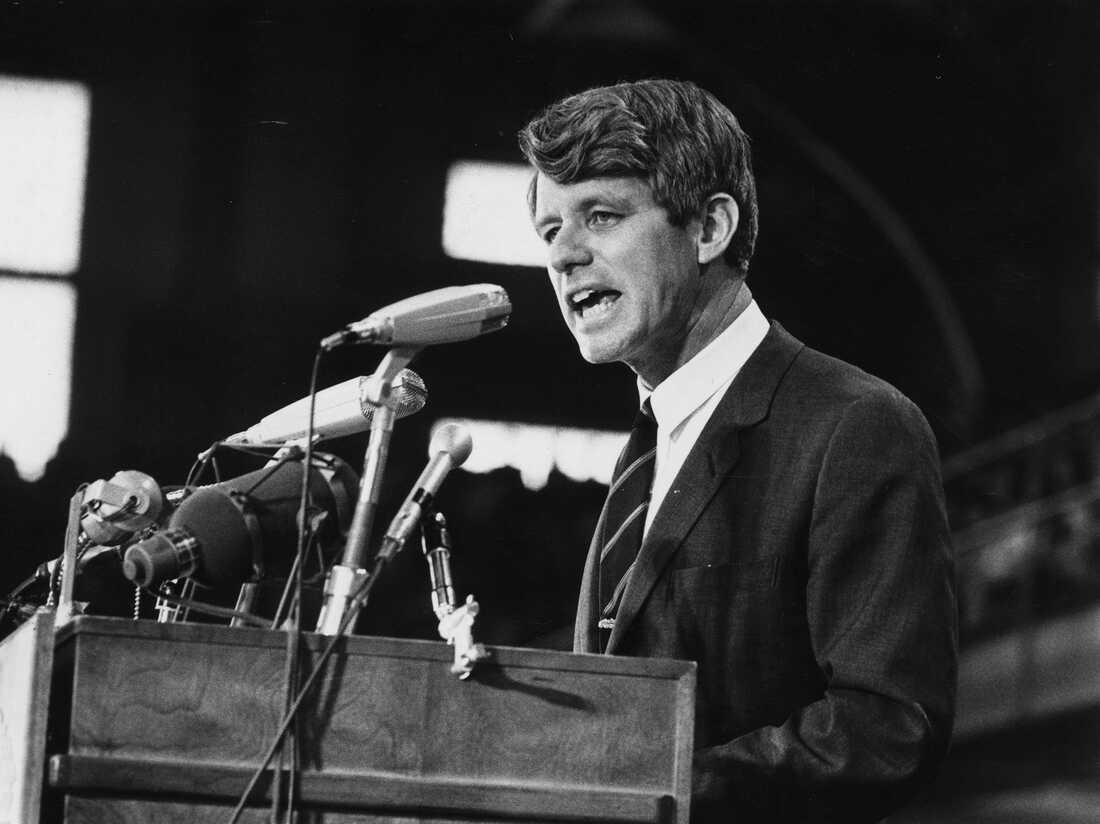

Above: America’s 39th President, Robert F. Kennedy (D - NY), widely viewed as Grigori Romanov’s “great international nemesis”.

The most critical threat of all to Romanov and the Kremlin was the “Kennedy Doctrine” launched by the American President at the start of his term. After years of gestures toward peaceful co-existence and treating the Soviets as an equal, Kennedy was, essentially, calling their bluff that Soviet communism in any way seriously rivaled American capitalism and democracy. This was apparent in the “Second Space Race”, but also in international relations. Through a combination of flexing American soft power, technological superiority, and increased diplomatic, financial, and economic pressure (as recommended by the likes of his “wise man” - George F. Kennan), Kennedy’s long term geopolitical strategy aimed to break apart the Soviet Union along ethnic and national lines, and win the Cold War once and for all without firing a single shot. This, in Romanov’s mind, could not be allowed.

But Romanov was playing a very dangerous game. He quickly found himself in the same spot Yuri Andropov had before his ouster: knowing full well that the USSR’s current course was unsustainable and also knowing that he was, in a sense, powerless to alter it. Thus, Romanov’s main response to the Kennedy Doctrine was, unsurprisingly, raising military spending.

In 1982, defense gobbled up an astonishing 70 percent of the USSR’s national budget, and supplied billions of dollars worth of military aid to the United Arab Republic (UAR), Libya, South Yemen, the PLO, Cuba, and North Korea - all “sworn enemies” of the United States. That aid included tanks and armored troop carriers, hundreds of fighter planes, as well as anti-aircraft systems, artillery systems, and all sorts of high tech equipment for which the USSR was the main supplier. Romanov's main goal was to avoid an open war while also placating Dmitry Ustinov and Andrei Gromyko back home. But even this left the Soviets coming up short.

Stated Soviet military spending in US dollars for the year of 1981 came to about $75 billion. Though the actual amount was probably higher (given the sheer size and scope of the military establishment in that country), it still accounted for less than half of US spending - just north of $155 billion heading into 1982. America’s allies in NATO also outspent the USSR’s in the Warsaw Pact, while simultaneously devoting smaller percentages of their national budgets to defense. The cracks in the “paper tiger” that was the Eastern Bloc were beginning to show.

Still, Romanov pressed on.

Despite privately recognizing that the Invasion of Afghanistan “had been a mistake”, he continued the occupation and counterinsurgency campaigns. He did dispatch foreign minister Gromyko to explore options for a negotiated withdrawal from the country, but these attempts were quickly dismissed as “half-hearted” by Western observers. So too did Romanov cease even the pretense of working toward arms-reductions with the United States. When asked by a Western journalist in 1982 if there would be any negotiations on the subject before the next scheduled summit in Geneva in 1985, Gromyko (speaking for Romanov) flatly denied the idea. The consensus in the Kremlin was that vague, nebulous “peace movements” in the United States and other Western countries would force an American surrender in the Cold War before the Soviet system collapsed. This line of thinking was either naive or delusional. It was also potentially catastrophic, a proverbial ticking time bomb that threatened to destroy the Soviet Union from within.

Yet, few at the time were willing to admit as much.

Even as some within the political sphere (particularly Mikhail Gorbachev) attempted to raise the alarm about the costs associated with dedicating so much of the Union’s stagnating treasury to “propping up” satellite states around the world, who contributed essentially nothing back to the USSR, nothing meaningfully changed. Romanov liked Gorbachev personally. He even felt that Gorbachev might make for a fine successor to Gromyko as foreign minister once the latter retired. But he could not stomach the idea of pulling back Soviet spending anywhere in the world. To do so, to Romanov (and Ustinov and Gromyko) would represent “surrender” to the West and admitting that the Union was not as strong as it claimed to be. Strength was the only thing holding the Soviet bloc together, Romanov and the hardliners believed. It was not unlike the “useful opulence” strategy employed by the Ancien Regime in France just prior to the French Revolution.

That is to say, all of this was a recipe for disaster.

Sure enough, a pair of them erupted before the end of Romanov’s first years in power: The October Crisis of 1982 (including the so-called “Hårsfjärden War” with Sweden of all places) and the September and November Crises of 1983, which would, once again, bring the world to the brink of thermonuclear war.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: President Kennedy Tackles the Crime Epidemic

@President_Lincoln Amazing chapter! VERY proud of RFK for continuing to stand agaist the soviet union.

Uh oh! *cue the dun dun dunnn sound effect*That is to say, all of this was a recipe for disaster.

Sure enough, a pair of them erupted before the end of Romanov’s first years in power: The October Crisis of 1982 (including the so-called “Hårsfjärden War” with Sweden of all places) and the September and November Crises of 1983, which would, once again, bring the world to the brink of thermonuclear war.

RFK about to have his "Cuban Missile Crisis" event, it seems.

Nice read-up on events in the USSR, where the Troika continues clinging onto it's power (even though Suslov dies and is replaced by Chernerko then Romanov), the Soviets realise that they're in a mess in Afghanistan, but are in too deep to back out and signs are showing that the USSR is crumbling apart at it's foundations already.

Will be looking forward to the next chapter!

Indeed. The time has come to see if the Revolution can outlive the generation that brought it into being.Well well well...Interesting Times for the USSR, it seems...

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed. RFK is definitely living up to his brother's mantra of "We dare not tempt them with weakness..." Ironically, he'll be (in my estimation) a much more effective Cold Warrior than Reagan was IOTL. Foreign Policy is Bobby Kennedy's wheelhouse.@President_Lincoln Amazing chapter! VERY proud of RFK for continuing to stand agaist the soviet union.

Cheers! Yeah, the current crop of Soviet leadership really can't see the forest for all the trees, so to speak. By trying to win (or at least, continue to contest) every single possible engagement with the west, they are stretching their resources to the breaking point, much as they did IOTL. The true test of whether the Soviet Union can survive ITTL will be if it is able to produce the reforms that, IOTL, proved elusive following the August coup of 1991.Uh oh! *cue the dun dun dunnn sound effect*

RFK about to have his "Cuban Missile Crisis" event, it seems.

Nice read-up on events in the USSR, where the Troika continues clinging onto it's power (even though Suslov dies and is replaced by Chernerko then Romanov), the Soviets realise that they're in a mess in Afghanistan, but are in too deep to back out and signs are showing that the USSR is crumbling apart at it's foundations already.

Will be looking forward to the next chapter!

LET'S GO! The kennedy's for the win!Thank you! Glad you enjoyed. RFK is definitely living up to his brother's mantra of "We dare not tempt them with weakness..." Ironically, he'll be (in my estimation) a much more effective Cold Warrior than Reagan was IOTL. Foreign Policy is Bobby Kennedy's wheelhouse.

Or a coup in 1988August coup of 1991.

Hard not to root for Bobby Kennedy here considering the abysmal record of the USSR throughout this TL to be honest.

The internal machinations of the Soviet Government whenever a leader dies or is replaced are always a joy to read in TTL. You capture the historical characters and their actions and flaws so well!

The internal machinations of the Soviet Government whenever a leader dies or is replaced are always a joy to read in TTL. You capture the historical characters and their actions and flaws so well!

Thank youHard not to root for Bobby Kennedy here considering the abysmal record of the USSR throughout this TL to be honest.

The internal machinations of the Soviet Government whenever a leader dies or is replaced are always a joy to read in TTL. You capture the historical characters and their actions and flaws so well!

No problem your very welcome 👍 Both sides are enjoyable to read aboutThank youI admit that my American bias may be showing a little here. But given that the US' policies in the Cold War have been a tad more peaceful and human rights-centered ITTL, I think it's justified. I also find the political machinations of the Kremlin fascinating to write about.

Well done, as always. Love to read up on behind the scenes events in the Kremlin. Romanov, like OTL Soviet leaders, is biting off more than he can chew, mainly by spending so much on the USSR's military.

Things are heating up. I think RFK is handling the Soviets the best way possible. And of course at the end of the day it's Soviet pride that's really gonna cause the downfall of the USSR. Can't wait to read about those 3 events mentioned at the end of this chapter, looks like Bobby will get three Missile crises altogether. That ought to get the heart pumping. Outstanding as always.Chapter 155 - Who Can it Be Now?: (Another) Changing of the Guard in MoscowAbove: The view from Red Square - state funeral for Mikhail Suslov, January 28th, 1982 (left); Grigory Romanov, Suslov’s eventual successor as Chairman of the Presidium and First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (right).

“Who can it be knocking at my door?

Go 'way, don't come 'round here no more

Can't you see that it's late at night?

I'm very tired and I'm not feeling right

All I wish is to be alone

Stay away, don't you invade my home

Best off if you hang outside

Don't come in, I'll only run and hide

Who can it be now?

Who can it be now?

Who can it be now?

Who can it be now?” - “Who Can it Be Now?” by Men at Work

“Sometimes, history needs a push.” - Vladimir Lenin

The rise of Solidarity in Poland (and the political and economic turmoil it portented) created another “crisis of confidence” in the Kremlin. The authority of the Polish United Workers’ Party (that country’s ruling communist party) eroded significantly, and there were some in Moscow who feared that Poland might break away from Soviet-style communism altogether. Acting in his role as head of the Politburo, First Secretary Mikhail Suslov created (and subsequently chaired) a commission on how to handle the “Polish situation”.

Beginning on August 28th, 1980, the commission began to consider Soviet military intervention in order to “stabilize” the region. This course of action was favored by defense minister Ustinov, but opposed by Suslov and Gromyko, the other members of the “troika” leading the USSR at that time. It was also opposed by Wojciech Jaruzelski, First Secretary of the Polish United Workers' Party. Jaruzelski was able to persuade the commission that a Soviet military intervention would only aggravate the situation.

Suslov would write of his decision not to send in the tanks, “If troops are introduced, that will mean a catastrophe. I think that we all share the unanimous opinion here that there can be no discussion of any introduction of troops.” The First Secretary did manage to persuade Jaruzelski to declare martial law in his country until the situation could be contained, however.

The election of Robert F. Kennedy to the presidency of the United States posed a further problem for Moscow. Though both candidates had been hawkish on the campaign trail (by American standards), the troika had strongly hoped for a victory by Ronald Reagan. Reagan was seen as a “lightweight” on foreign affairs, whom the troika and their allies could have “dealt with quite easily”. After all, his inflammatory rhetoric would have made him look, in Gromyko’s words, “like a buffoon” on the international stage. Bob Kennedy, on the other hand, was well-known in Moscow for his “cutthroat nature” and “ruthlessness” while simultaneously enjoying widespread respect and stature abroad. Under Kennedy, the US would once again begin to seriously challenge Soviet influence across the globe.

Suslov made plans for how to “counter” Kennedy, especially after the American president survived the attempt on his life by Mark Chapman, but before the Kremlin could enact them, Suslov developed a coronary thrombosis - the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. Four days later, on January 25th, 1982, Suslov died of arteriosclerosis and diabetes just after four in the afternoon, Moscow time. He was 79 years old.

Though little mourned by the Soviet public, Suslov would be missed dearly by many on the politburo. He was widely regarded as the party’s foremost expert on Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy and theory, a true ideologue, committed to communist revolution.

In the immediate aftermath of Suslov’s death, Konstantin Chernenko - his deputy - ascended to the position of “Acting Chairman of the Presidium and Acting First Secretary” until such time as mourning for Suslov could be completed and a new Chairman chosen. Chernenko himself was no spring chicken, already 70 years old in January 1982 and reportedly in poor health. During Suslov’s funeral, Chernenko struggled to be heard, even while mic'd, as he read the eulogy. Chernenko was also ethnically Ukrainian; not a deal breaker for a Soviet leader, but, by the unspoken rules of Russian supremacy within the USSR, not ideal.

Above: Konstantin Chernenko (left); Dmitry Ustinov (center); and Andrei Gromyko (right); the three men who attempted to restore order to the Kremlin in the wake of Comrade Suslov’s death in early 1982.

At the time of his ascent to the country's top post, Chernenko was primarily viewed (as Suslov himself had been) as a transitional leader who could give the Politburo's "Old Guard" time to choose an acceptable candidate from the next generation of Soviet leadership. By this time, they had already more or less settled on their man: Grigory Vasilyevich Romanov.

Romanov was born on February 7th, 1923 in Novgorod Governorate into a peasant family. Romanov served as a soldier in the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War (World War II). Romanov later joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1944. He graduated from the Leningrad Shipbuilding Institute in 1953, and became a designer in a shipyard. He fulfilled several important posts in the party committee of the enterprise he was working at and later in the Leningrad city and regional party committees. In September 1970 he was elected as First Secretary of the Communist Party Committee of the Leningrad Region. In this position, he gained a reputation of being a skilled organizer and well versed in economic matters, winning defense investment for Leningrad over other regions and attracting the attention of the party’s upper echelon, including Yuri Andropov, who subsequently brought him to Moscow and helped promote him in June 1979 to the very prestigious and influential post of a secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU responsible for industry and the military-industrial complex. Throughout the last few months of Andropov’s tenure, Romanov became seen as one of his closest allies.

Indeed, contrary to subsequent evaluations of Romanov by both western observers and the hardliners themselves, it is perhaps more accurate to describe Romanov as a “moderate” than a “conservative”. An ardent supporter of Andropov's comprehensive program for the reform, renewal, and further development of socialism in the Soviet Union and beyond, Romanov simply believed in the Andropov style of reform (economy-first) in contrast with others, such as Gorbachev and Tereshkova, who also favored various degrees of political liberalization.

What Romanov succeeded in, however, was blending in with whatever group he found himself in politically. He made himself into a chameleon, shifting his rhetoric to placate and woo whatever faction he happened to be speaking to at any given time. This, combined with their perception of him as “sympathetic to conservative views” led Chernenko, Ustinov, and Gromyko to favor Romanov as the Union’s next leader.

Following the four days of mourning prescribed by the Soviet constitution after Suslov’s death, Chernenko summoned the politburo and put forth the motion to name Romanov to all positions of leadership. Some questioned the wisdom of handing power to this relative “newcomer”. After all, Romanov had only been a member of the central committee for the last two and a half years. If nominated, his would be the most rapid ascent in the history of Soviet politics. At 57 years old, he was the second youngest member of that body (ahead of just Mikhail Gorbachev - 49). But Ustinov and Gromyko supported the move, believing that not only was Romanov “one of them”, but also that they could “mold” this “naive newcomer” into governing as they saw fit. With any resistance to the motion, tokenistic or hidden (as was the case of Gorbachev), the motion passed. Grigory Romanov became the first leader of the Soviet Union to have been born after the Revolutions of 1917. This was truly a watershed moment in Soviet history and politics.

Above: Grigory Romanov’s first official portrait after being sworn in as Chairman of the Presidium and First Secretary of the Soviet Union on January 30th, 1982.

Somewhat insecure in his new role, Romanov did not rock the boat immediately after entering office. By the beginning of 1982, the stagnation of the Soviet economy was obvious, as evidenced by the fact that the Soviet Union had been importing increasing amounts of grain from the U.S. throughout the 1970s. As soon as President Robert F. Kennedy revoked the grain embargo, the Soviets not only resumed their orders, but increased them. This staved off popular revolt over the availability of bread and other essential goods, but did little to improve the Soviet Union’s prestige and influence abroad. Again, Romanov, like his mentor Andropov, understood the need for reform, but the economic system was so firmly entrenched that any real change seemed impossible.

Eschewing any radical economic or political reforms then, Romanov’s immediate domestic policy leaned heavily toward “restoring discipline and order” to Soviet society. He promoted a small degree of candor in politics and mild economic experiments similar to those that had been associated with the late Alexei Kosygin's initiatives in the mid to late 1960s. Simultaneously, he launched an anti-corruption drive that reached high into the government and party ranks. In an attempt to “model” his new ideal for Soviet leadership, Romanov lived modestly. Eschewing the "decadent dachas" of his predecessors, he favored a simple townhouse in Moscow. He began a public relations campaign to show himself as a “new” kind of leader: professional; efficient; and able to restore the Soviet Union to its “rightful place in the world”.

Unfortunately, the new leader’s situation abroad was no better.

Romanov immediately faced a series of foreign policy crises: the hopeless situation of the Soviet army in Afghanistan; the aforementioned threat of revolt in Poland; growing animosity with the People’s Republic of China under Hu Yaobang; the Iran-UAR war in the Middle East; and brewing trouble in eastern and southern Africa.

Above: Soviet troops battle insurgents in Afghanistan, circa 1982 (left); Mujahideen rebels, also circa 1982 (right).

By 1982, the Soviet military presence in Afghanistan had increased to approximately 125,000 soldiers as fighting across the country intensified. The complication of the war effort gradually inflicted a higher and higher cost on the Soviet Union’s treasury as military, economic, and political resources became increasingly exhausted. Despite the best efforts of both the Soviets and their allied communist regime in Kabul, resistance to their control over the country not only persisted, but intensified.

To begin with, the political situation shifted, first in 1977, when Pakistan (the USSR’s ally in the invasion) withdrew from the conflict following new elections, which saw the ruling PPP’s leader toppled from power, replaced with an antiwar prime minister. The new Pakistani government renounced their previous war-aim of founding a “client state” of “Pashtunistan” and instead welcomed “any Pashtuns who wished to join Pakistan” to do so. With the withdrawal of Pakistan, many ethnic Pashtuns no longer saw the invading Soviets as their defenders or liberators, and instead began switching sides, joining and supporting various resistance groups. The conflict took on an increasingly religious tone for the Afghani people, who saw the Soviets as “godless communists”, hell bent on subjugating their country to “forced secularization and imperial domination” from Moscow.

Though the resistance groups were by no means united (they fought amongst themselves almost as much as they fought the Soviets), they held a number of key advantages over the invaders.

First, most of the resistance fighters were either from Afghanistan or had at least lived in the country for several years. They were thus far more familiar with the country’s mountainous geography than the Soviets. They fought with a mix of religious zeal and national fervor, willing to give anything, including their lives, to defend their home. Finally, since 1975, the rebel groups had been receiving aid in the form of financial support, arms, supplies, and military training from a coalition of states, including: the United Kingdom; Saudi Arabia; and, mostly through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the United States.

President George Bush famously called the Mujahedeen “freedom fighters”, a phrase which would be repeated by Ronald Reagan on the campaign trail in 1980. While Mo Udall had felt “uneasy” about arming and aiding them directly, when Robert Kennedy took the oath of office in 1981, he did not share Udall’s reservations. Though Kennedy did not arm just anybody looking for American resources (he explicitly forbade the CIA and its director, former head of Naval Intelligence and Admiral Bobby Ray Inman, from meeting with anyone but indigenous Afghan mujahedeen, let alone arming, training, coaching, or indoctrinating them), he did authorize nearly $5 billion in aid throughout the course of the program - codenamed Operation Hurricane. This was all part of his administration’s renewed commitment to “containment”, as opposed to the “détente” of the last decade and a half.

Above: America’s 39th President, Robert F. Kennedy (D - NY), widely viewed as Grigori Romanov’s “great international nemesis”.

The most critical threat of all to Romanov and the Kremlin was the “Kennedy Doctrine” launched by the American President at the start of his term. After years of gestures toward peaceful co-existence and treating the Soviets as an equal, Kennedy was, essentially, calling their bluff that Soviet communism in any way seriously rivaled American capitalism and democracy. This was apparent in the “Second Space Race”, but also in international relations. Through a combination of flexing American soft power, technological superiority, and increased diplomatic, financial, and economic pressure (as recommended by the likes of his “wise man” - George F. Kennan), Kennedy’s long term geopolitical strategy aimed to break apart the Soviet Union along ethnic and national lines, and win the Cold War once and for all without firing a single shot. This, in Romanov’s mind, could not be allowed.

But Romanov was playing a very dangerous game. He quickly found himself in the same spot Yuri Andropov had before his ouster: knowing full well that the USSR’s current course was unsustainable and also knowing that he was, in a sense, powerless to alter it. Thus, Romanov’s main response to the Kennedy Doctrine was, unsurprisingly, raising military spending.

In 1982, defense gobbled up an astonishing 70 percent of the USSR’s national budget, and supplied billions of dollars worth of military aid to the United Arab Republic (UAR), Libya, South Yemen, the PLO, Cuba, and North Korea - all “sworn enemies” of the United States. That aid included tanks and armored troop carriers, hundreds of fighter planes, as well as anti-aircraft systems, artillery systems, and all sorts of high tech equipment for which the USSR was the main supplier. Romanov's main goal was to avoid an open war while also placating Dmitry Ustinov and Andrei Gromyko back home. But even this left the Soviets coming up short.

Stated Soviet military spending in US dollars for the year of 1981 came to about $75 billion. Though the actual amount was probably higher (given the sheer size and scope of the military establishment in that country), it still accounted for less than half of US spending - just north of $155 billion heading into 1982. America’s allies in NATO also outspent the USSR’s in the Warsaw Pact, while simultaneously devoting smaller percentages of their national budgets to defense. The cracks in the “paper tiger” that was the Eastern Bloc were beginning to show.

Still, Romanov pressed on.

Above: Soviet Mil Mi-24 helicopters (left) and state of the art MiG-31 jet fighters (right); both aircraft were flown extensively during the latter phases of the Soviet war in Afghanistan.

Despite privately recognizing that the Invasion of Afghanistan “had been a mistake”, he continued the occupation and counterinsurgency campaigns. He did dispatch foreign minister Gromyko to explore options for a negotiated withdrawal from the country, but these attempts were quickly dismissed as “half-hearted” by Western observers. So too did Romanov cease even the pretense of working toward arms-reductions with the United States. When asked by a Western journalist in 1982 if there would be any negotiations on the subject before the next scheduled summit in Geneva in 1985, Gromyko (speaking for Romanov) flatly denied the idea. The consensus in the Kremlin was that vague, nebulous “peace movements” in the United States and other Western countries would force an American surrender in the Cold War before the Soviet system collapsed. This line of thinking was either naive or delusional. It was also potentially catastrophic, a proverbial ticking time bomb that threatened to destroy the Soviet Union from within.

Yet, few at the time were willing to admit as much.

Even as some within the political sphere (particularly Mikhail Gorbachev) attempted to raise the alarm about the costs associated with dedicating so much of the Union’s stagnating treasury to “propping up” satellite states around the world, who contributed essentially nothing back to the USSR, nothing meaningfully changed. Romanov liked Gorbachev personally. He even felt that Gorbachev might make for a fine successor to Gromyko as foreign minister once the latter retired. But he could not stomach the idea of pulling back Soviet spending anywhere in the world. To do so, to Romanov (and Ustinov and Gromyko) would represent “surrender” to the West and admitting that the Union was not as strong as it claimed to be. Strength was the only thing holding the Soviet bloc together, Romanov and the hardliners believed. It was not unlike the “useful opulence” strategy employed by the Ancien Regime in France just prior to the French Revolution.

That is to say, all of this was a recipe for disaster.

Sure enough, a pair of them erupted before the end of Romanov’s first years in power: The October Crisis of 1982 (including the so-called “Hårsfjärden War” with Sweden of all places) and the September and November Crises of 1983, which would, once again, bring the world to the brink of thermonuclear war.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: President Kennedy Tackles the Crime Epidemic

Share: