It's alright! Although Dole will probably become Whip once Rumsfeld becomes Leader tbhChairman of the RNC perhaps?

He did serve that role for a brief stint ('71-'73) OTL before being succeeded by Bush Sr. for a year, so maybe he got that role TTL as well

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Blue Skies in Camelot (Continued): An Alternate 80s and Beyond

- Thread starter President_Lincoln

- Start date

It may be the last chance he gets

I am throwing my support behind one more Nixon attempt...

And how well would he even do?It may be the last chance he gets

Although it would be exciting to see if he can cause a contested convention cause I feel like he would go full Nixon at that point

I wanna add on to this cause like imagine it:And how well would he even do?

Although it would be exciting to see if he can cause a contested convention cause I feel like he would go full Nixon at that point

Reagan of course lands in first place in the delegate and PV count.

Nixon in second while Dole and Haig share third / fourth place.

Nixon would then pull out all stops to get Haig's endorsement ( VP? Defense? FP Concessions? ) while trying to peel off the more conservative delegates from Dole's camp and pulling whatever he can from Reagan's. This is also aided by him turning up the corruption and nastiness by 100.

If he actually wins the RNC would have there own 1968 DNC

Could happenI wanna add on to this cause like imagine it:

Reagan of course lands in first place in the delegate and PV count.

Nixon in second while Dole and Haig share third / fourth place.

Nixon would then pull out all stops to get Haig's endorsement ( VP? Defense? FP Concessions? ) while trying to peel off the more conservative delegates from Dole's camp and pulling whatever he can from Reagan's. This is also aided by him turning up the corruption and nastiness by 100.

If he actually wins the RNC would have there own 1968 DNC

NOT A CROOKYeah and I can imagine even if Nixon doesn't do something that makes him resign. I have a feeling he's gonna be a really polarizing figure

NIXON 1980

"Now more than ever."

I am throwing my support behind one more Nixon attempt...

I must say I'm interested to see an older more senile Nixon in office see if he screws it up just as bad as he did in OTLLove how after I suggested Nixon everyone is now jumping on the bandwagon 😂

Hahah true.I must say I'm interested to see an older more senile Nixon in office see if he screws it up just as bad as he did in OTL

That man was as sharp as ever. I still don't think he should be too bitter but you never know. What if he just uses his term to spite the right wingers who kept on screwing with him?I must say I'm interested to see an older more senile Nixon in office see if he screws it up just as bad as he did in OTL

On another note, how is him and Pat's health. Did she still have her stroke in this timeline?

You know it genius! Whenever we hear his surname, we knew already he's on the negative side of American History.Love how after I suggested Nixon everyone is now jumping on the bandwagon 😂👀

Last edited:

Make way for Tricky Dick!!!

I am throwing my support behind one more Nixon attempt...

Speaking of how is Nixon’s daughters doing ITTL?Yeah how is Pat ITTL?

Deleted member 145219

I wonder what would have happened to Nixon and the GOP had Eisenhower not hit the campaign trail for him in the closing days of the campaign. Leading to a larger loss than OTL, and Kennedy winning California. Probably won't be hearing too much about Illinois and Texas, given that the margins in those states would be larger. And Kennedy would have California, and a few other states and their electoral votes.

I have to wonder about Rockefeller buying himself the nomination in 1968 after Romney implodes.

I have to wonder about Rockefeller buying himself the nomination in 1968 after Romney implodes.

Chapter 125

Chapter 125: “The Men Behind the Wire” - The Troubles Reach Their Bloody Peak

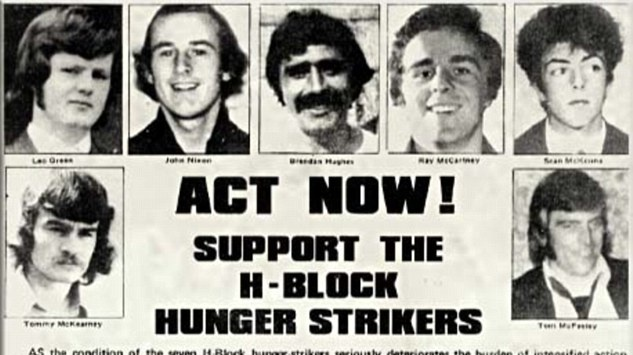

Above: A propaganda image for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), showing female members “mugging” a Unionist in Belfast (left); the infamous “Hunger Strikers” (right).“Armored cars and tanks and guns came to take away our sons

But every man must stand behind the men behind the wire”

- “The Men Behind the Wire”, the Wolfe Tones

“I joined the civil rights marches because it was obvious that some people were being treated better than others. We used to accept bad housing and bad jobs. Most of my friends just went to England and didn’t bother looking for work here. I had never voted and neither had my parents, brothers or sisters. There was no point, you couldn’t really change anything. The marches awoke a sense of injustice in me and a determination to be treated equally.”

- An unnamed Catholic resident of Derry, Northern Ireland

“It was all ‘the Catholics this and the Catholics that’ [with Loyalists] living in poverty and us lording it over them. People looked around and said, ‘What, are they talking about, us? With the damp running down the walls and our houses not fit to live in.”

- A Protestant housewife in Belfast, interviewed by the BBC

The mid to late 1970s were, without question, the bloody peak of the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland, known colloquially as “The Troubles”. In the years after “Bloody Sunday”, and following the Provisional IRA’s “home bombing” campaign of terror throughout the United Kingdom, all parties involved grew increasingly eager for some kind of peace. The issue was, as it had always been, however, complex and multi-faceted. To fully explain the difficulties in bringing the conflict to a close, it is helpful to first examine the situation from a bird’s eye view, to try and understand the geopolitics of the situation.

Beginning in 1971, the Tory governments, first of Randolph Churchill, then Margaret Thatcher, had attempted to clamp down on the violence by instituting direct rule of Northern Ireland from London. Due to claims of voter fraud and election tampering from both the Loyalist and Nationalist factions, the Northern Irish parliament was no longer seen as legitimate in the eyes of many Northern Irish citizens. The Royal Ulster Constabulary, as well as regular British army soldiers attempted to maintain law and order, and fought back both the Provisional IRA and the Ulster Volunteer militias. Neither side, however, were happy with the British government’s involvement.

Loyalists constantly accused London of going “soft” on the Provo's and other republican groups, for fear of inciting some kind of international incident with the Republic of Ireland, or damaging relations with the United States, Canada, and other nations with large Irish diaspora, who were generally amenable to Irish nationalism. Nationalists, meanwhile, cringed at the idea of Churchill, the son of the man who had first unleashed the loathed “Black and Tans” on Ireland a generation earlier, sending British soldiers to Irish soil to “keep the peace”. They accused first his, then Thatcher’s governments of unfairly favoring the Loyalists, and never punishing their militias to nearly the same degree as they did any captured IRA members.

For their part, the British public would have liked for nothing more than to wash their hands of the situation. Outside of Northern Ireland, support for continued union, even if it meant military occupation, was quite low indeed. Many English, Scottish, and Welsh citizens of the UK felt that this was a Northern Irish issue, not a British one. Many in the press and public began to discuss the possibility of an independent Northern Ireland. This was, in large part, the goal of the PIRA’s terror campaign. They hoped that they might dissuade the British public, and thereby the British government, from continuing the fight. This contingency was discussed, by some in both the Churchill and Thatcher governments, but never with any degree of seriousness. Both PMs would never have considered such a move, even as some members of Labor’s shadow cabinet met openly with the IRA to discuss a possible ceasefire. Talks, which the PIRA leaders believed, would lead to Northern Ireland becoming a separate dominion, not part of the Commonwealth. An “independent” Northern Ireland of this kind would then be a much easier target for their true goal: an open and bloody civil war, with an intervention by the Republic on behalf of Catholic Nationalists, if need be.

In both Dublin and London, this possibility was treated as, in Churchill’s words, “an utter doomsday scenario”. In 1975, the Republic of Ireland’s Foreign Minister, Garrett FitzGerald discussed in a memorandum both his country’s anger at the Shadow Ministers meeting with the leadership of the IRA, an illegal organization, as well as their hopes that such a scenario (complete British withdrawal from Northern Ireland) not take place. According to FitzGerald, such a move would result in three possible scenarios, none of them good.

The first, orderly British withdrawal followed by Northern Irish independence, was seen as the “best of the worst” scenarios. Followed by a possible repatriation of the island, which would have seen Catholic/Nationalist and Protestant/Loyalist citizens relocated to different parts of Northern Ireland and the borders between the two countries redrawn. And finally, the absolute worst of the worst: the north descending into anarchic civil war. FitzGerald concluded that while the Irish government would prefer that none of these contingencies come to pass, it held relatively little power to stop them should the British withdrawal. Worse, there were some in the Republic’s government who secretly hoped for the situation in the north to break down. If it did, it could provide a casus belli for the Republic to march its (official) army into Derry and Belfast to protect the rights of Catholics and Nationalists, thus resulting in a possible reunification of the island. FitzGerald and the rest of the Fine Gael government were well aware, however, that such a move would only provoke an Ulstermen response of apocalyptic proportions. Such would be the culmination of more than five decades of their absolute worst fears made manifest.

Thus, without a solution readily available, the British stayed. The conflict continued.

Distraught that their tactics had failed to elicit the desired British withdrawal, the Provisional IRA allowed their ceasefire with British authorities to expire in early 1976. They began to develop a strategy they called “the Long War”, which involved a less intense but more sustained campaign of violence that could continue indefinitely. Despite war weariness setting in on both sides, the work of the “Peace People”, winners of the 1976 Nobel Peace Prize, and other groups seemed incapable of producing a lasting settlement. In the case of the Peace People, their campaign lost momentum and support amongst the general public when they asked Catholics and Nationalists to “inform” on members of the PIRA to British authorities. In February 1978, the PIRA bombed La Mon, a hotel restaurant in County Down. The following year, in August of 1979, they attempted to assassinate former Governor-General and Viceroy of India, World War II hero Lord Mountbatten and several members of his family and entourage. Thankfully, SAS agents were warned of the plot ahead of time and managed to relocate Mountbatten and the other targets at the last moment. Still, it was clear that unless something changed, the 1980s would begin yet another decade of bloodshed in Northern Ireland and beyond.

…

The Labour Ministry which began following the “Winter of Discontent”, certainly had its work cut out for it in a myriad of areas. The British economy was, like its American counterpart, suffering from the worst effects of “stagflation”. Both unemployment and inflation were high. The British public reported feelings of “fear and anxiety” about their nation’s future. Thus, Prime Minister Denis Healey spent the first year or so of his ministry focused on these and other domestic and economic issues. The attempted assassination of Lord Mountbatten in August of 1979, however, proved a bridge too far. The new PM would have to deal with the Troubles, head on.

Despite the British government’s prior efforts toward “normalization” in Northern Ireland, the conflict showed no signs of slowing. Aspects of this policy - “normalization” - included the removal of internment without trial and the removal of political status for paramilitary prisoners. Beginning in 1972, paramilitaries were tried in juryless “Diplock” courts to avoid intimidation of prospective jurors. On conviction, defendants were to be treated as ordinary criminals, rather than political prisoners or captured enemy combatants. Resistance to this policy among republican prisoners led to more than five hundred of them in the Maze prison initiating the "blanket" and "dirty" protests.

Further complicating the situation, many members of Sinn Fein, which had become arguably the Provisional IRA’s political wing, had vowed to begin contesting elections in both Northern Ireland (as abstentionists) and in the Republic. Though many saw this as a sign that a political solution would prove impossible, the new British PM looked at this, and at increasing war weariness on both sides of the conflict, and sensed an opportunity.

Healey took his first meaningful step when his government announced that the parliament of Northern Ireland would re-open, with elections scheduled to be held in the spring of 1980. Ever the pragmatist, Healey believed, probably correctly, that direct rule from London had resulted only in increasing bloodshed and escalating the conflict, by giving both sides hope that someone outside of the north may intervene militarily on their behalf. British troops would remain in place, but Healey insisted, Northern Irish citizens would once again have their own devolved parliament with which to resolve issues. Though Sinn Fein would be allowed to contest seats, Healey had members of his government quietly reach out to more moderate members of the party, as well as more moderate elements of Unionist parties and groups.

Healey’s grand plan for peace, as it were, was a gradual one. He knew that the “Long War” strategy being employed by the PIRA could only work if they continued to be supplied with weapons, particularly small arms and explosives. Despite claims by the nationalists that they were “more than capable” of supplying their own weapons, Healey wisely recognized that without shipments of arms and money from outside sources, the paramilitaries would slowly wither on the vine, further increasing desire for peace. In this regard, Healey and his Foreign Secretary, James Callaghan, played a complex diplomatic game to close off all possible avenues of funding and supply. While doing this, Healey and his Home Secretary for Northern Ireland, Don Concannon, continued to forge alliances with moderates on both sides of the conflict.

Slowly, surely, the foundations were being laid for a political settlement.

Above: A Republican mural in Belfast, commemorating the hunger strikes of 1981.

In the meantime, however, the deaths continued.

1981 would bring the infamous hunger strikes. Ten republican prisoners, including Bobby Sands, died of starvation in “the Maze” prison, after Healey’s government refused to reverse the policy of Normalization. Though Healey took a great deal of criticism for his decision, he stood by it, claiming that to alter British policy toward paramilitary prisoners would jeopardize the complex peace project he and his allies were working toward. Nevertheless, the hunger strikes resonated among many nationalists throughout the north. More than 100,000 people attended Sands’ funeral mass in West Belfast. Sands was even elected to Parliament on an “Anti H-block” ticket. H-Block being another name for the “Maze” prison.

As the years passed, however, Healey’s plan finally began to work. The United States and other countries with large Irish diasporas clamped down on money being sent overseas to the IRA. Meanwhile, both Scotland and Canada did the same with money being donated to the UVF and other loyalist militias. Nations like Gaddafi’s Libya decided that potentially damaging relations with the west were not worth whatever notoriety and limited payment they could receive by shipping weapons to the paramilitaries.

Slowly, painfully slowly, a political solution, involving power sharing in the Northern Irish parliament by those moderate Unionists and members of Sinn Fein became increasingly possible. Other reforms would need to be made, including the renaming of the Royal Ulster Constabulary to the “Police Service of Northern Ireland” (which would be required, by law, to recruit at least 50% Catholics each year), the removal of Diplock courts, and a new phase of normalization, which meant the removal of redundant British army barracks, as well as the gradual withdrawal of regular army troops. These and other terms would not be made official until after two ceasefires, one by the UVF in 1986, the other by the IRA in 1987, the so-called “Good Friday Agreement” was finally signed by leaders of both sides in 1988, shortly after the conclusion of PM Healey’s time in office.

While, of course, Healey and the Labour governments of the 1980s, as well as the Republic of Ireland’s governments, led by Garrett FitzGerald and Charles Haughey, deserve a great deal of credit for their careful politicking and diplomacy to get the peace deal signed, moderate elements of both the nationalist and unionist movements must also be recognized.

After more than twenty years, “The Troubles” were finally coming to an end. This would not mean the end of sectarian divides in Northern Ireland, far from it, but at least this was a start.

Next Time on Blue Skies in Camelot: The White House Delivers Some Difficult News

Share: